This post originally appeared at The Nation.

Fifty years ago, Andrew Goodman, a 20-year-old anthropology major at Queens College, went down to Mississippi for Freedom Summer. His first stop was Philadelphia, Mississippi, where he and Mickey Schwerner, a 24-year-old graduate student in social work at Columbia University and James Chaney, a 21-year-old volunteer with the Congress for Racial Equality from Meridian, Mississippi, were sent to investigate a church burning. Schwerner and Chaney had spoken at Mount Zion Methodist Church over Memorial Day, urging local blacks to register to vote.

In 1964, only 6.7 percent of African-Americans were registered in Mississippi and not a single one in Philadelphia’s Neshoba County. The fight for voting rights was the reason Goodman traveled to Mississippi. “He just thought it was unfair that an American citizen of voting age was restrained and stopped from voting,” said his older brother, David.

On June 21, 1964, the young civil rights activists were arrested by the Neshoba County police and then abducted by the Klan. Their bodies were found 44 days later in an earthen dam. Goodman and Schwerner, both white, had been shot once. Chaney, who was African-American, had been mutilated beyond recognition. Martin Popper, the attorney for the Goodman family, called it “the first interracial lynching in the history of the United States.”

The murders of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner were the starkest example of the brutality the Freedom Summer volunteers encountered from local whites. Freedom Summer “produced almost as many acts of violence by local whites as it did black voters,” wrote historian David Garrow. Mississippi didn’t change until Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965. “A lot of people lost their lives getting that Voting Rights Act into place,” said David Goodman.

The legislation eliminated the literacy tests and poll taxes that for so long prevented blacks from registering to vote in Mississippi and other Southern states and made sure those states didn’t adopt new voter suppression tactics in the future. The VRA transformed Mississippi and the rest of the country. Today, the Magnolia State has more black elected officials than any other state.

The 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer happens to coincide with the first anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v Holder, where the Supreme Court’s conservative majority invalidated Section 4 of the VRA on June 25, 2013. As a result, states like Mississippi, with the worst history of voting discrimination, no longer have to clear their voting changes with the federal government.

Section 4 provided the formula for covering states that had to submit their voting changes under Section 5 of the VRA (known as “preclearance”). Chief Justice John Roberts struck down Section 4 for two reasons: it was based on outdated data from the 1960s and 1970s, he argued and violated what he called the “fundamental principle of equal sovereignty” among states. Though Roberts conceded “voting discrimination still exists; no one doubts that,” he stated that the “extraordinary measures” of the VRA were no longer justified.

Think voting discrimination is largely a thing of the past?

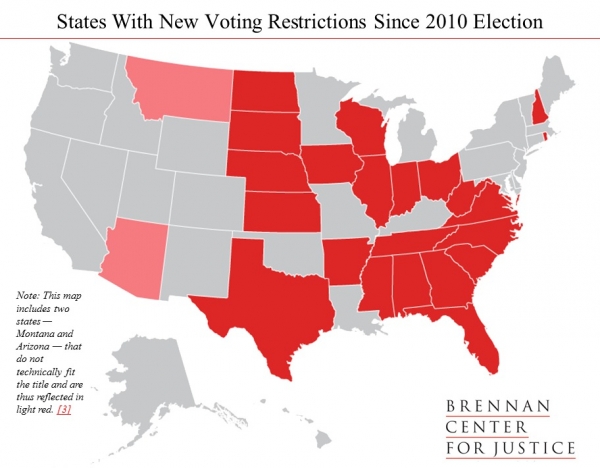

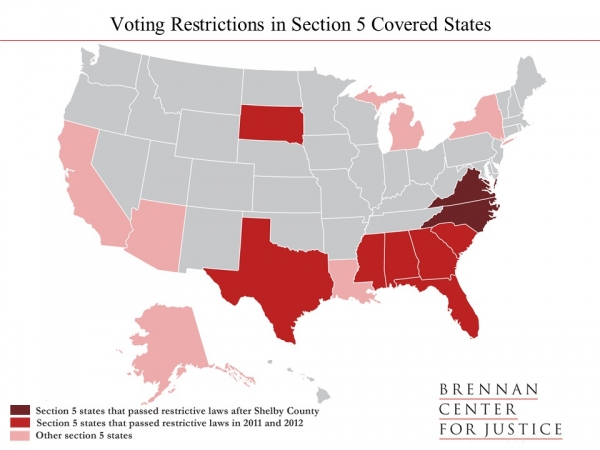

Take a look at this map, courtesy of the Brennan Center for Justice:

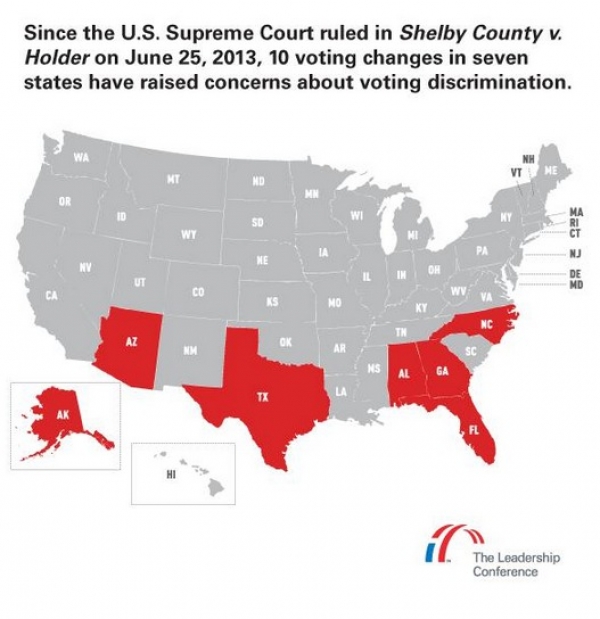

And this map:

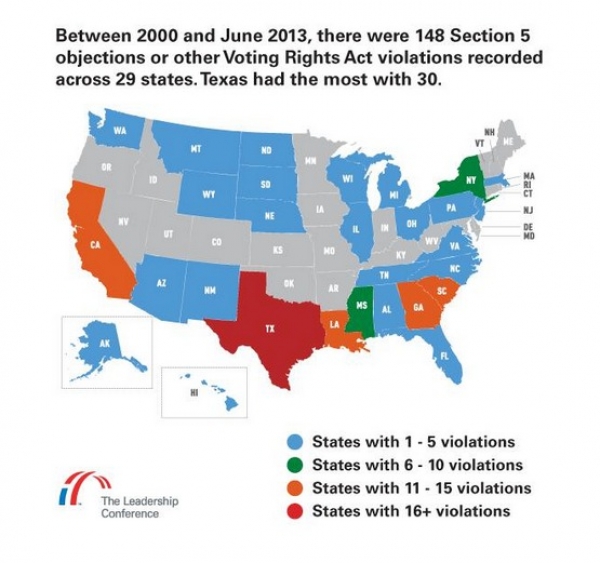

And this map, via the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights:

Some relevant facts Roberts neglected to mention:

Since the 2010 election, 22 states have passed new voting restrictions, according to the Brennan Center. This includes requiring strict voter ID to cast a ballot, cutting early voting, making it harder to register to vote and rescinding voting rights for non-violent ex-felons. New restrictions will be in place for the first time in fifteen states in the 2014 election. All across the country, we’re seeing the most significant push to restrict voting rights since Reconstruction.

Partisanship is a strong motivating factor for the voting changes — GOP legislatures or governors enacted 18 of the 22 new restrictions.

So is race. According to the Brennan Center: “Of the 11 states with the highest African-American turnout in 2008, 7 have new restrictions in place. Of the 12 states with the largest Hispanic population growth between 2000 and 2010, 9 passed laws making it harder to vote.”

These disturbing facts suggest that the strong protections of the VRA are still needed. Nearly two-thirds of the states previously covered under Section 5 of the VRA, nine of 15, passed new voting restrictions since 2010.

Take another look at the maps above. You’ll see that the South continues to restrict voting rights more aggressively than anywhere else in the country. What has changed in recent years isn’t the South but the fact that states like Kansas and Ohio and Wisconsin and Pennsylvania have adopted Southern-bred voter suppression tactics. Just when the VRA should’ve been expanded to cover the surprisingly wide scope of 21st century voting discrimination, the Supreme Court instead gutted the law.

“Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet,” Justice Ginsburg wrote in her dissent. The central irony of the decision is that it was pouring when the Supreme Court removed the umbrella designed to protect voters from discrimination.

What happened next was entirely predictable. Within two hours of the decision, Texas implemented a voter ID law judged to be discriminatory by the federal courts. Two months later, North Carolina passed the harshest package of voting restrictions in the country.

Local jurisdictions previously covered by the law have responded in kind. Reports MSNBC’s Zack Roth:

Georgia lawmakers changed the date of city council elections in Augusta from November to July, a time when black turnout is traditionally far lower — a tactic that goes back to Jim Crow days. In Pasadena, Texas, voters approved a new “at-large” scheme for electing council members that made it much harder for Hispanic candidates to win office. A similar scheme, adopted by a school district in Beaumont, Texas, was blocked by the Justice Department under Section 5, but went into effect this year.

Since the Shelby decision, 10 jurisdictions in seven states have enacted potentially discriminatory new voting changes that would’ve been subject to review under Section 5, according to the Leadership Conference.

A good case study is Decatur, Alabama, a city of 55,000 in the northern part of the state. For most of the 20th century, whites controlled every important position in Decatur, which is 20 percent black. The first black city councilman wasn’t elected until 1988, as a result of a landmark lawsuit under the VRA, when the city shifted from citywide at-large elections to five single-member districts, including one majority-black district, for the city council.

In 2010, Decatur passed a referendum adopting a council-manager form of government, with two at-large districts for the city council and three single-member ones. The catch was that the new plan would eliminate the city’s only majority-black district. In 2011, the city submitted the change for federal approval under Section 5. After DOJ requested more information, Decatur withdrew its submission. The new plan seemed dead. But following the Shelby decision, the new system is set to go into effect. (It’s now being challenged in court by voting rights lawyers in Alabama.) As a result, the city’s lone black councilman, Billy Jackson, may soon be out of a job.

Despite these developments, new legislation to update Section 4 is stalled in Congress. Few Republicans — including the 57 House Republicans who voted for the VRA’s overwhelming reauthorization in 2006 and are still serving — are willing to support it. Eric Cantor, whose backing would have been critical to the bill’s passage, will soon be leaving Congress.

Cantor was one of three Republicans who traveled with John Lewis and David Goodman on a congressional pilgrimage to Mississippi in March to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Freedom Summer. “He was very moved by the story of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner,” Goodman said. Cantor told Goodman: “This voting issue is not a partisan issue.” It didn’t used to be, but now it is.

On Wednesday, the Senate Judiciary Committee will hold a hearing on the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2014. No hearing is currently scheduled in the House. House Judiciary Chairman Bob Goodlatte is said to believe that a remedy for the Supreme Court’s decision is not needed. Past history and present circumstances suggest otherwise.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.