LISTEN TO THIS CONVERSATION

EDITOR’S NOTE: Our times at last have found their voice, and it belongs to a Pakistani American: Ayad Akhtar, born in New York, raised in Wisconsin, an alum of Brown and Columbia, actor, novelist, screenwriter and playwright, with an ever-soliciting eye for the wickedness and wonders of the world. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, his plays revel in the combustions of an America on edge, bursting with excess — too much of everything, from wealth and impoverishment to religion, rage and radicalism, from sad hearts and hollow souls and shifting identities to the glorious celebration of money. Perhaps that should be the inglorious celebration of money: E Pluribus Unum transformed into Every Man a Midas.

His latest play is Junk. One critic calls Junk “an epic, strutting, restless, sexually charged, slam-bang-wham piece of work… A Shakespearan history play of spiraling national consequence.” That’s too modest; Junk is not only history but prophecy. A Biblical-like account of who’s running America — and how. Last week, before I announced that I would be signing off in retirement again, I asked Ayad to join me for this conversation, the last in a series. We had a great time together; it was worth the wait. —Bill Moyers

TRANSCRIPT

(Note: The audio version above is an edited version of the conversation which was recorded in Dec. 2017 and is published in full below.)

Bill Moyers: When your play Junk came to an end, I sat there in my seat, marveling that what I had just seen on the stage was fiction which from my own experience as a journalist I knew to be true.

Ayad Akhtar: Well, Picasso says that art is the lie that tells the truth. So if this absorption in the fictional doings of people is oriented toward the truth in some way — the truth of society or a character or a situation — then you get to the end hopefully having had that experience. I’m very gratified to hear that you did.

Moyers: I thought, “Akhtar must have worked on Wall Street. At a hedge fund or in private equity or at one of the giant predatory banks.”

Akhtar: I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this, Bill, because I believe that to understand how the world is put together today — to have a sense of what it means to be human in that world — you need a deep understanding of finance. That’s an unfortunate statement. I am not sure it would have been true of the 14th century or even the 17th century, but I think it is true of our era. It is impossible to understand what it means to be human without understanding how being human has been redefined through finance.

Moyers: Did you ever work in finance?

Akhtar: I never did. My parents were doctors, and dad made a sort of bargain with me that if I read The Wall Street Journal every day and took a look at Barron’s on the weekend, he would pay my rent for awhile, and I did. I was in my early 20s and it was the beginning of that tech bull run of the ’90s. Tina Brown had just taken over The New Yorker and I read profiles in the magazine of Mikhail Baryshnikov sitting cheek by jowl with profiles of Herb Allen of Allen and Co., the boutique investment firm. Financiers were making the pages of The New Yorker, and you would go to book parties and to theater openings and people were talking about their stock portfolios.

Moyers: Because…

Akhtar: Because money had entered the culture in a big way. I was new to it. Being conversant in terms of finance gave me cultural cache. That’s the selfish motive that I had in those circles. But the more I studied finance and began to understand it and the more I palavered with folks who are part of that world, the more I began to say to myself: “So this is why things are the way they are.”

Moyers: So what in particular inspired you to write Junk?

Akhtar: When I had the good fortune of being awarded the Pulitzer Prize [for Disgraced], I thought, “Well, very little good can come of this, because either I’m going to believe it and become a writer who’s disconnected from my own weaknesses that I need to keep working on, or I’m going to be defensive about it and say, “Well, if I deserve this thing, I have to write in a way that will prove something.”

Moyers: To yourself as well as to others.

Akhtar: So I thought, “Well, this is a psychological conundrum. And the only way out of it is to take a big artistic risk. Now, I had wanted to write a very large play about finance for a long time. So I sat down and started to do so, knowing that if at this moment in my career I wrote a play with 30 characters in it that was three acts and 68 scenes, it might actually get produced right now.

Moyers: Why now?

Akhtar: Because money permeates culture. So there was a bit of strategy in this, but there was also a real desire to address what I saw as this shift in human values in the world. I’ve written a couple of other things that deal with finance as well, but this one was much more ambitious.

Moyers: But why not the Roaring ’20s, when the roof blew off, the stock market came down, and the Great Depression followed. Why not the first Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century?

Akhtar: Oh, there could be a fascinating play about the robber-baron era and maybe even the relationship between JP Morgan and Teddy Roosevelt. There was a back and forth then between politics and capital. But in a way, those stories are not as relevant ultimately to us today as what happened in the 1980s. I think the difference in the ’80s was that the philosophical soil of the earlier American psyche was ready to embrace unfettered individualism as the rubric of behavior and decision-making. The collective mindset experienced a fracture in the ‘80s that we are still dealing with.

Moyers: It’s clear from seeing Junk that the seeds for Trump’s ascension were sown in the ’80s, yet you finished writing it before he even announced he was running. There was a religious fervor in the ’80s about money and finance and debt.

Aktar: Donald Trump rose to power on untold amounts of debt. And the great awakening is exactly what it was. It was the great awakening and the construction of a new church, and we are now living in the world that church created.

Teresa Avia Lim and Michael Siberry in a scene from the Lincoln Center Theater production of Junk by Ayad Akhtar.

(Photo by T Charles Erickson © T Charles Erickson Photography)

Moyers: The church of…

Akhtar: Finance.

Moyers: And God is…

Akhtar: The economy.

Moyers: How so?

Akhtar: Well, think about it: an abstraction that we placate and that we observe with holy attention on a regular basis whose well-being tells us more about our well-being than our own well-being tells us. When the economy is healthy, we are a hopeful people. When the economy falters, presages of doom are never far off. It’s mythic thinking. Through statistics and analysis we have substituted an abstraction that somehow is speaking eloquently about every aspect of our national and political and personal lives.

Moyers: One of your memorable characters says it well — the financial journalist Judy Chen. Here’s what you had her say:

This is a story of kings, of what passes for kings these days. Kings bedecked in Brooks Brothers and Brioni, enthroned in sky-high castles and embroiled in battles over — what else? — money. When did money become the thing? I mean the only thing? Upgrade your place in life or your prison cell for a fee. Rent out your womb to carry someone else’s child. Buy a stranger’s life-insurance policy, pay the premium until they die, then collect the benefits. Oh, and cash: Whose idea was it to start charging us to get cash?

Akhtar: Those oppositions go to the heart of a money-obsessed culture: Upgrade your place in line or your prison for a fee. Rent out your womb to carry someone else’s child. Buy a stranger’s life insurance policy and wait for them to die. What she’s suggesting is that the entire compass of human existence is now defined by the imperative to monetize every possible interaction. This is what the system has created; it’s created this aberration where everyone is looking to benefit in a financial way off of every transaction they are having with everyone else. This is the ideal. And then people wonder why don’t we have a society anymore. Why is there no sense of mutual well-being? Because we are pitted against each other like merchants.

Moyers: It was in the mid-’80s that I interviewed the mythologist Joseph Campbell — the very era in which your play takes place. Campbell said you can tell what’s informing a society by its tallest building. When you approach a medieval town, the cathedral is the tallest thing in the place — the cathedral, looming over the cottages where people lived. When you approach an 18th-century town, it is the political palace that’s the tallest. And when you approach a modern city, the tallest places are office buildings, the centers of economic life.

Akhtar: The skyscraper. The glass-and-steel skyscraper. Exactly what I’m saying. We are beholden as religious creatures to this powerful new religion that was being born in the ’80s and is reshaping our lives and our society.

Moyers: You caught that fervor in the amazing array of people in your play. The critic Chris Jones, writing in the Chicago Tribune, describes your cast as “Rollicking, raging, rule-breaking, MBA-sporting dudes in suits with ravenous zeal in their eyes.” Did you personally know people like that, or did you invent these characters?

Akhtar: I think I have had enough experience of the testosterone-laden environment of high finance. In some people I recognized a sort of gentle philosophical urbanity, and in others, that fevered ambition you saw on stage, so that I could write convincingly about them. But I did a fair amount of research. I got some help from two of my very close friends — one of them a high-powered businessman who used to be a mergers-and-acquisitions lawyer at a top firm and now runs a hedge fund, and another close friend who owns an investment bank in London. I would constantly share the work with them and ask, Am I getting something right? Am I getting something wrong? So there’s been a long process.

Moyers: And the result — 30 different people on stage, yet with something in common.

Akhtar: What they had in common is that they were all in pursuit of the only way to be heroes in our era. They’re all trying to triumph on terms that are not just material but — well, spiritual. They’re knights. They’re kings. They are—

Moyers: —grubbing for money, let’s face it.

Akhtar: Hey, that’s all that’s left if you want to really affect the world today. I remember reading about George Soros as a very young man, as an immigrant coming from Hungary, recognizing that in order to have decisive impact on the world, he needed to be very, very wealthy. And that is a recognition that more and more people are coming to understand: Without money, you cannot fight. In order to have political agency, you have to have capital.

Moyers: You have said elsewhere that “our culture is giving people very few opportunities to demonstrate their surpassing excellence other than the making of money.”

Aktar: If you are a person of endowment confronted with fears about how to make your way in the world, Bill, there are really not enough opportunities for you to exhibit your excellence and secure your future. So you make the choice that puts you into the system. The system is the thing redistributing wealth. When you are in the system, the system works one way. It does not work two ways; it does not work five ways. It works one way. And working that way, with maybe a flavor of compassion if you want, or a flavor of ruthlessness if you want, depending upon your personality — that’s what’s going to ensure your success.

Moyers: Is that what you meant when you said that “We are living in a time when the abstracted activities of our economic life are being enriched. And the real ones, impoverished.”

Akhtar: Thomas Piketty talks about that in his book On Capital. He basically says that real growth is 2 percent. Capital grows at 5 percent. Sooner or later, that is a tension that is going to be played out. And that’s what we’re seeing. The CEO of GM famously said, “I don’t want to make cars anymore. I want to make money.” When you have GM rather make loans than make cars because the loans produce 5 percent on the cars they make, you’re abstracting — it’s an abstracted interaction. The car is an excuse for a fixed-income payment that a customer is going to make over time, that can be sold. And then insurance can be sold against that. And the fixed-income payment on the insurance can also be sold. You have this derivative chain reaction that creates a whole sector of activity that is not connected to anything concrete except at its first iteration. And frankly, you have the creation of wealth that is never really funneled back into the system, because people are not paying for a service. They’re paying for a potential profit or a potential fixed-income payment.

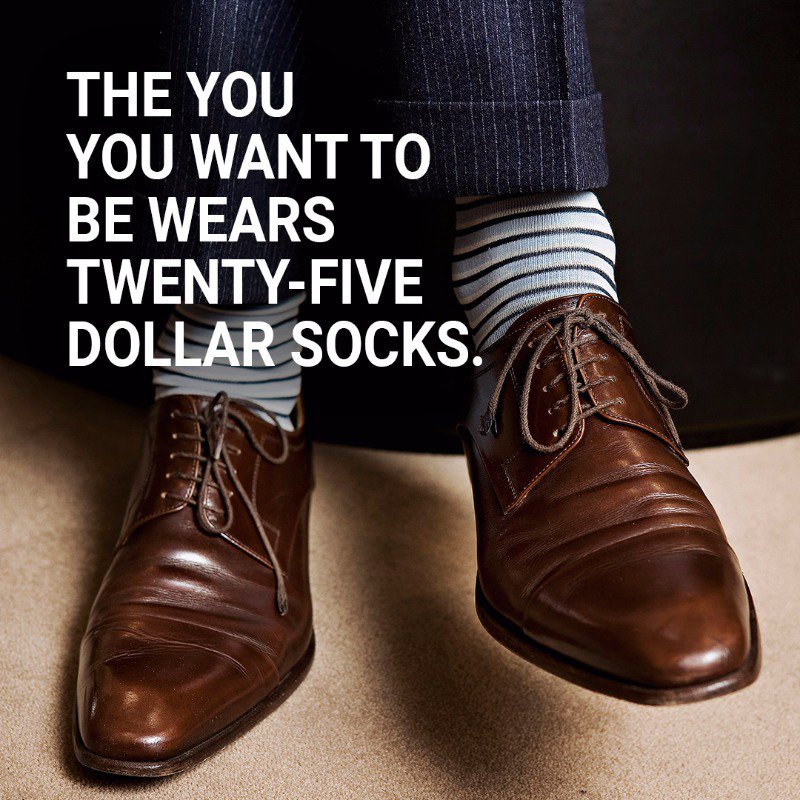

Moyers: I was walking home yesterday and saw a sign in the window of one of the many banks in the neighborhood. I took this picture of it: “The you you want to be wears $25 socks. Get a little extra spending power with the new HSBC Gold Mastercard credit card.” In other words, spruce up your identity with socks bought on credit.

Get a little extra spending power with the new HSBC Gold Mastercard® credit card. (Image courtesy of HSBC / Twitter: @HSBC_US)

Akhtar: Because they can sell your debt. Then the next person down that chain is going to sell that debt. And it’s all going to create fees for the people who are selling it along the way. This is what the world economy has become. We’re talking leverage ratios of 30-40 to 1, Bill. Once upon a time that would have been insane.

Moyers: Once upon a time there were scriptural prohibitions against usery.

Akhtar: And for good reason, because there are spiritual implications.

Moyers: Yes?

Akhtar: By spiritual I mean that which concerns us most individually and collectively, that which is of ultimate concern, the fulfillment of our deepest potential and our most vivid relationship to each other, to ourselves and to reality.

Moyers: And now?

Akhtar: We’ve become a republic of consumers. Those rights and privileges that were available to us upon entering a collective contract, a social contract—

Moyers: “We, the People,” right?

Akhtar: Sure. A social contract that enables us to enjoy the benefits of mutual protection, education, health. Today those are available to you if you can buy them. And the corporate state offers you the lowest price. That’s your compact. There is something deeply terrifying about how completely it’s taken over.

Moyers: Terrifying?

Akhtar: I was in Hamburg, Germany, almost a year ago. I was in a boat, taking a tour of the harbor. Hamburg is a rich port city, one of the richest in Europe. And I saw container cranes everywhere, and I realized that in another 10 to 15 years, whatever isn’t already automated will be so. Robots guided by artificial intelligence will be unloading what stevedores have been handling. I thought about how this change will affect the city, a city made rich by the work of the port. Now, the Germans will do their best — unlike us, here in the US — to mitigate the deleterious effect on the social body. But they won’t be able to mitigate it completely. And I wondered: “What is the justification to the system? What rationale is being proffered to the larger social body to justify the damage these changes will bring to it?” The answer: Increased productivity, of course. But then I thought: “The benefits of increasing productivity are so lopsided in favor of the few, the owners. And it hit me: “How they have gamed the system!”

Moyers: You didn’t have to go to Hamburg, Ayad, to see that.

Akhtar: But then I thought, Don’t be lazy. Push past the obvious. And this is what bubbled up: It can’t all be JUST about the rapacious elite. Even powerful owners can’t get away with that — at least not in Germany — without some legitimizing compensation. There must be some benefit — perceived and true — to the social body for a transformation this significant to have any chance. What could be that benefit? And again the answer hit me: The lowest price. Offering people the lowest price has become the new promise, the new covenant, socially. Once that was usually offered to a member of society as a citizen: You have the right to representation, to certain social goods. No longer. What you have the right to now is the lowest price. So you see the rise of Amazon as the corporate centerpiece of contemporary life, because it’s servicing the only system that any longer makes sense: a system of customers. We have all been transformed, fundamentally, from citizens into customers.

Moyers: All this was prompted by seeing stevedores creating wealth for the city now being replaced by robots guided by artificial intelligence?

Akhtar: Something else: There’s no longer a need for the owners to give back, except to give you a lower price. Cut their taxes, increase their profits, just give us lower prices in return. We’re customers, after all, not citizens. And the terrifying thing is that — look, as I said, we all desire to demonstrate our excellence and to be the most that we can be. When all that’s really offered you is the arena of money, because it’s the reigning value system, people are going to head for the realm where they can use and demonstrate their excellence, and that’s the realm of money, finance. I mean, what unifies Oprah Winfrey and Bill Gates and Michael Milken? Smart people. But it’s really that they have made a lot of money. And in making a lot of money, they have become people we are supposed to pay attention to.

Moyers: Especially in a society where you say we have idealized and legislated the accumulation of wealth as our primary national value. What do mean by “legislated”?

Akhtar: Well, generation after generation we have offered people — the social body, now increasingly customers — the catechism that trickle-down economics is going to rebound to the benefit of the general public. Take Les Moonves, CEO of CBS. He said something to the effect that “Trump may not be good for the country, but he’s good for business.”

Moyers: Higher ratings, more advertising, more revenue. Trump draws audiences no matter what he says.

Akhtar: Yes, but historically, the only reason CBS has a license is because they made a commitment to serve the public good. So with Moonves it’s either lacking any kind of understanding of what he is the steward of, or it’s deeply hypocritical. And the climate in America has changed so much that the irony is lost on almost everything.

Moyers: Maybe he was kidding.

Akhtar: I don’t think so. Where did this idea that the animal spirits of the business community must be placated above all others? This is an ideology which has taken over American life.

Moyers: Certainly many in that community don’t think they need a moral environment to make money. And that’s the point in Junk.

Akhtar: Yes.

Moyers: Everyone is corrupted.

Akhtar: Or ultimately takes the money. In a country where that’s all that’s left, you’re an idiot if you don’t do that. Because if you don’t do that, there is no republic of citizens to sustain you. You’re on your own. That’s the great paradox of being young today. Young people are released into the workplace with student debt in a form of indentured servitude to the corporate state. This is the vehicle by which the social body has been transformed into a kind of neofeudal order for young people.

Moyers: Do you think those young people who find college too expensive for them understand that it’s because those colleges have borrowed so much money?

Akhtar: Two trillion dollars they are paying debt on. Colleges increase tuition. What do they do with it? They leverage it further. They take out more debt, which causes another rise in tuition. This is the metaphor for the larger economy. And this is why we are living in an era of taxation without representation. We are being taxed every time we pick up a phone to deal with our technology, because of the consequence of leverage and debt, in fees and percentages, with every point of contact with the system. It is a bleeding of the American people that has no recourse. We have no way of representing ourselves to those who are taking the money from us.

Moyers: Call it oligarchy — the wealth of the private sector joined with the power of the state. Don’t you think that’s one reason for the pervasive sense of powerlessness today? Money determines value, determines who gets to change things, and without it, you feel hopeless and helpless.

Akhtar: Yes, the incentives are to keep the people who can make change in the system, to keep them justifying the system. That’s the problem. And in part it has to do with the collapse of, again, the spirit of community. It has to do with the rise of individualism and a shift in education. The people who could challenge the system, even change the system, go out there and make so much money they can buy that big house in the Hamptons and get very, very comfortable. Everybody today understands that trade-off.

Moyers: Including politicians in Washington. Money in politics has largely displaced the ballot box in determining who gets represented, certainly who gets heard.

Akhtar: Increasingly, the political class is preparing for a lucrative life in the private sector afterward. That seems to be the new evolving model of what political life is really all about.

Moyers: [As many as] 300, 400 lobbyists in Washington today, mainly for large and financial organizations, are former members of Congress.

Akhtar: —who are now making seven and eight figures a year.

Matthew Rauch and Steven Pasquale in a scene from the Lincoln Center Theater production of Junk by Ayad Akhtar. (Photo by T. Charles Erickson © T Charles Erickson Photography)

Moyers: By the end of your play, Ayad, it’s clear who’s won.

Akhtar: Wall Street’s won. Money’s won. The system.

Moyers: The private-equity owners and the hedge-fund managers, they’ve won.

Akhtar: And there’s a reason they won. They won because they defined the world. They won philosophically and they prevailed. And what they have to offer is technology and cash. They’ve created a society in which those two things are really all that matters.

Moyers: Which brings me to the main character in Junk, Robert Merkin, whom you created around the real figure of Michael Milken. Back in the ’80s Donald Trump may have thought of himself as the king of the deal, but it was Milken who was celebrated as the king of junk bonds. By the way, did you know anything about junk bonds before you wrote this play?

Akhtar: I just knew that there were companies where you could buy bonds in companies where they paid you a lot higher return.

Moyers: Because they took bigger risks.

Akhtar: Yes, and because those companies were less viable entities. They were not an IBM. They were more like Saratoga-McDaniels, the small holding company in my play that made bowling balls and mint extract and whatnot.

Moyers: And the junk bonds were more likely to default and end up worthless, because they promised those big returns and had to risk to get them.

Akhtar: But what was interesting about recognition in the ’80s is that if you tracked the performance of high-yield debt — high-risk debt, otherwise known as junk bonds — over the course, say, of a 50-year period, they actually outperformed the market. You could account for the default ratio and still make more money if you invested intelligently in junk. And this recognition was what really fueled Michael Milken’s rise. Because he was the first person to really embrace what was otherwise treated as if it were toxic.

Moyers: And is this why you built your story around him?

Akhtar: For a few reasons. Of course the play is a play, and I don’t want folks to come see it expecting to see a realistic portrait of Michael Milken per se. But let’s face it: I think he’s the great financial genius of the 20th century. And in so many ways he embodies some of the big contradictions of capitalism, qua capitalism. And I knew if I could find a way, humanly, to embody him in the play, the audience’s relationship with him would mirror their own relationship with capitalism. It would mirror their relationship with its justifying ideologies, with its predations, with its immorality, with its amorality, and with capitalism’s benefits. And ultimately, Bill, with its multivalence — that it is an ever-shimmering, ever-changing thing.

Moyers: So just to summarize the plot briefly: The protagonist in the play, Robert Merkin, is plotting to buy a steel company in Pennsylvania, cut the work force, strip the assets, sell them off to make a fortune, and walk away very, very rich.

Akhtar: Yes, that’s one way of looking at it. But what he would say is that this company has fallen on hard times, it’s vulnerable. It has some businesses that are still viable. We’re going to finance the takeover of this company. We’re going to focus management on the parts of it that are viable, and we’re going to sell the ones that aren’t. Of course there are going to be consequences to the labor force, but those consequences are coming, one way or another. Remember Hamburg? All we are doing is speeding up a transition and we are effectively removing the sclerosis around the corrective process of capitalism, known as creative destruction. And I think that it’s a vision of capitalism that would be tough to argue with.

Moyers: Yes, but at the same time, both Robert Merkin in your play and Michael Milken in the ’80s—

Akhtar: —used illicit means to put pressure on shareholders and management, to entice them into a takeover. At that time a hostile takeover was still anathema to many people, something considered very wrong morally. And you had to induce shareholders and management to feel the benefits of a takeover before you could take them over. One of the ways you did that was by manipulating stock price and making them feel richer as the stock price rises. And then when the rumors of takeover disappear, the stock price drops — and that gap, that feeling of loss, becomes a foundation for the argument.

Moyers: And Merkin, like Milken in real life, pushes that argument too far — and goes to prison for violating security laws.

Akhtar: Security laws, yes.

Moyers: Of course Milken, as some will remember, gets out of jail long before he has served his full sentence. He even gets to keep most of his fortune. While Merkin — fret not, I’m not going to give away the end of your play and reveal what happens to your main character—

Akhtar: Well, he keeps selling debt. Let’s put it that way.

Moyers: Let it rest there.

Akhtar: You’re trying to hold on to the spoiler, but …

Moyers: Yes, I am, but we know Michael Milken’s arc, so let’s stick with that for a minute. He can’t go back to Wall Street, but he’s allowed to keep most of his fortune. Becomes a big philanthropist. People convene under his auspices. His outfit publishes a very interesting journal. He wins, although he can never again work on Wall Street. What does this turn of events say about capitalism?

Akhtar: That it’s easy to criticize capitalism and even easier to enjoy its benefits.

Moyers: Exactly.

Akhtar: And that’s the big paradox that we’re in, and how to sit inside that paradox is the big question. As F. Scott Fitzgerald once said, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” And that’s why I don’t think a unipolar critique of capitalism is going to have any effect. There has to be room for understanding what we humans are made of, of what we have built with capitalism, in order to understand how to shift the system. I think a shift is necessary, and a lot of people in finance know this. But the system has a concussive momentum that no individual can stop. There has to be a transformation at the level of consciousness.

Moyers: You certainly don’t let anybody off the hook. You’re unsparing to all of your 30 characters.

Akhtar: And myself included. The journalist in the play is a stand-in for myself.

Moyers: Really? Judy Chen, the financial writer?

Akhtar: Obsessed with money. Just as I’m obsessed with writing about money. So I spent all my time reading Shakespeare and now I want to write about people who just make money?

Moyers: And Michael Feingold writes in The Village Voice — he calls it an exceptional play, by the way, says it couldn’t be more timely or factual — he writes that you “tell a story in which the greedsters and predators who run our financial world, had — or believed to some degree that they had — virtuous motives mixed in with their simple selfishness. And as a consequence. while nearly every character in the drama is both crooked and very hard to like, it’s constantly possible to see the good they thought they were doing. And in a few cases, even the modicum of good they actually did.” You don’t pass judgment on them.

Akhtar: That’s not my job.

Moyers: But you don’t deny that their collective actions lead to ruined lives, lost fortunes, broken marriages, suicide — and still you don’t stand in judgment of them.

Akhtar: I don’t think it’s my job to be a moralizer about my characters. What’s most important for me is to penetrate the quiddity of them, the essence of who they are, to reveal that through action. And to allow the audience enough space to be able to consider them as rich and complicated phenomena. I love all of them. I couldn’t write about them if I didn’t love them. I love that Merkin is wounded about how his father was left out of the investment banking sector by the white shoe firms, and how he’s driven by a desire to avenge the wrongs of his tribe—

Moyers: He’s Jewish.

Akhtar: He is.

Moyers: And at a time when Jews were not allowed into the white-shoe law firms or the big financial firms.

Akhtar: Right. And he also has a complicated relationship with his Jewishness. Because he doesn’t want other people to identify him simply as Jewish. So there’s this interesting identity politics at the core of him that I find fascinating. And to bring it home to both of us. People ask, “Did the Fourth Estate take the money?” Yes, they did — the journalists did. “And does labor capitulate to the temptations?” Yes, labor did. We’re all in the game together.

Moyers: But we don’t all go down together. There are winners.

Akhtar: That’s true too.

Moyers: Some survive and thrive.

Akhtar: I think what you’re saying is of course true. But Henry Ford, love him or hate him, and there’s lots of reasons to hate him, said something very essential, which is that if you cannot pay your workers enough to buy the cars they are making, you have a long-term structural problem. So even if the people you are saying are not going down yet, long-term there’s a structural problem. When the whole is not cared for, those at the top will suffer as well, eventually.

Henry Stram (standing) and Rick Holmes (seated) in a scene from the Lincoln Center Theater production of Junk by Ayad Akhtar.

(Photo by T Charles Erickson © T Charles Erickson Photography)

Moyers: You came at this by incorporating many perspectives. It’s like watching whirling dervishes dance.

Akhtar: I think one of the great limitations of storytelling is that it is always anchored in a single point of view and that we wish to see the world through the point of view of a protagonist. It’s a cognitive thing. An ancient thing. But unfortunately it doesn’t equip us to understand the real world. We’re living in a world where the system has its own logic. And that system cannot be understood just from the point of view of a single individual. A single person’s motivations, flaws, desires, cannot account for what is actually happening. And the only way to begin to approach an understanding of it, as I said, is through a kind of multivalence or a multiplicity of points of view. Which was the big formal challenge of this play — to write it from other than one point of view.

Moyers: And how did you resolve that?

Akhtar: I had a lot of help. My director, Doug Hughes, and I worked for three years. We did lots of workshops to get it right. We staged a wonderful production in La Jolla, where I learned a lot about how the audience was responding to the play and where they were choosing to take sides and how to invert that as quickly as possible, so that they could stay floating in the in-between spaces. I told a friend later that I had written in “a protracted, diligent, fever dream of inspiration.”

Moyers: Doug Hughes says that you write plays that bring onstage the things that trouble our society’s sleep. But there’s a lot of humor in Junk.

Akhtar: Well, we’re creatures not wanting to see truth very often. The Chinese have a saying that the truth people want to hear is the truth that’s sweet to the ear. So that’s why there’s a lot of humor in the play. But that’s about as far as I could go. I couldn’t put a positive spin on this. I spent so long thinking about it and I didn’t see the silver lining. Finance is not only conditioning and defining what we think of as human, but it’s tearing the fabric of collective well-being into shreds.

Moyers: Yet you refuse to say it’s just evil rich people sticking it to good poor people. This is more than the story of a rapacious elite.

Akhtar: Bill, I think the real bedrock of the story is a competition or a conflict, a war, a battle, between two visions of capitalism. One is a meritocratic vision of capitalism driven by a younger generation who see being better and smarter and stronger as more important than being white and male. And the other vision of capitalism is a more paternalistic vision, in which the owner is the stakeholder. It’s not the CEO who is being compensated. It’s the owner, and often multigenerational familial ownership. That capitalism, while keeping certain people out, and while guilty of certain sins, is also much more attuned to the consequences of its behavior and the consequences of its actions than this new meritocratic vision of capitalism is. So I’m staging the battle between these two stories, which in many ways is the battle at the heart of the American experience over the last 60 years.

Moyers: I was drawn to the surviving son of the family that originally owned and built the steel mill in Pennsylvania. I was drawn to him—

Akhtar: Of course.

Moyers: —but in the end I wasn’t sure about him.

Akhtar: Right. Because it was a dying order. And he wasn’t necessarily the right steward to preside over the transformation of his company into a new era. At one point he sits downstage and says to his investment bankers: “Is this the future? Is this what we have to look forward to? Getting squeezed from every side for every last penny?” Yeah, that is the future. And in order to be a steward of a major company, in our era, you have got to be OK with that logic. That’s a sad statement, but it’s a true statement. It’s the system money has created.

Moyers: One of the best scenes in the play is when Robert Merkin, your protagonist, tells his investors:

Steven Pasquale as Robert Merkin in Lincoln Center Theater’s production of Junk. (Photo by T Charles Erickson © T Charles Erickson Photography)

We’re Americans. We invented the automobile. We built the greatest steel mills the world has ever known. God bless America. Let’s set aside the revolting assumption that God doesn’t bless other nations, or that somehow an American father’s job is more important to his family than a Chinese father’s job is to his. Let’s just set aside those lies. Those delusions. And let’s stick with the facts. Fact: They are winning. Fact: We need to understand why. Fact: We need to change. When you stay blind, you don’t change. When you can’t change, you die. And that is what’s happening in this country right now.

Akhtar: That was the argument often invoked in the 1980s — we’re living in a dying order; we have to change. And Jim Stewart, author of Den of Thieves, who wrote about the play and Merkin in a recent column for the New York Times, called it a full-throated defense of global cosmopolitanism. Which it is. And it’s the essence of this meritocratic vision of capitalism — that capital is itinerant. Boundaries, borders, do not fundamentally exist. Money will move where it can to do the work for those who are its stewards. And that kind of unrootedness from nation, from community, from a particular location, is part of the problem that we’re dealing with. We all know that when Walmart moves into a community, a large portion of every dollar spent in that Walmart leaves that community. And in the process, as we also know, a lot of local businesses close because the big box store has moved in. This is a simple concrete example of what I’m talking about. People who resisted the argument back in the 1980s simply got run over.

Moyers: Which is why so many of us are troubled. There was a period in America — the reaction, for example, to the excesses of the industrial revolution and the power of the robber barons — when democracy developed as a check and balance on unfettered greed and wealth. And now…

Akhtar: Why does it have to be greed? Why don’t we call it the drive to excel? This part of the issue is for me that we moralize the accumulation of money before we even understand the implications of what it means in our personal lives. I think that your earlier point about Milken’s resurrection since he got out of prison plays on the same notion that the only way to atone for the greed is to demonstrate that one uses the money in a way that is not greedy.

Moyers: No, I’m trying to say that whether intended or not, the pursuit of wealth can wreck havoc in people’s lives, create lots of suffering, increase inequality.

Akhtar: I understand that. But what exactly is the question?

Moyers: The question is: Has the untrammeled pursuit of money turned democracy into an impotent fraud?

Akhtar: I think your language betrays the answer.

Moyers: Well, I am biased in favor of a more radical reading of our history than I was exposed to growing up. I came to believe we have to have strong and principled government to tame the intended or unintended damage produced by “creative destruction.”

Akhtar: Something I share, by the way. Look, I think what has happened is the restoration of a neofeudal order. And in the neofeudal order there’s a version of the landed gentry. That landed gentry owns capital. When you have access to vast sums of money, you have agency in the political process in a way that is actually commensurate with a real vote.

Moyers: Agency meaning power, you can change things. You can make things happen with money.

Akhtar: Exactly. And this shift in the idea of the individual political agent is so perfectly embodied in the Supreme Court decision of Citizens United. That so many people accept a decision like that reflects shifts in American life that don’t strike me as native to our being. Sure, de Tocqueville said in the early 1800s that the only thing Americans seemed to care about is making money. But I think that became more decisively true as celebratory individualism fractured our consciousness.

Moyers: As you said, our values fundamentally changed in the ’80s. And people who used to be proud of being good citizens began to think of themselves more as deserving consumers.

Akhtar: That’s right. Let’s go back to higher education and look at the transformation from another angle. Let’s say that native to the very nature of pedagogy is hierarchy, a teacher who knows something and a student who doesn’t. Now there is of course the possibility for an abuse of power in that situation to be sure, but the very nature of the transfer of knowledge implies that somebody knows something and somebody doesn’t. When you add customership into this equation and have students paying lots of money in order to be able to have access to the one who knows, that customer must be satisfied. Unfortunately, in pedagogy the transmission of knowledge can be unsatisfying. It can cause the student to come up against prejudices, lacunae in their knowledge, unease in their identity. That’s part of the process of growth. So in higher education, we are no longer in the business of teaching young people. We’re in the business of satisfying them as consumers. Education is a business.

Moyers: “I go to college, I pay tuition. I expect a good job from the exchange.”

Akhtar: That’s right, and you have no longer what I would call a society. You have a collection of data points, a marketplace. You have customers who are being promised the lowest price for health insurance, for education, for protection. Those things which are supposed to be your rights as a citizen are now products of the “free market.” They’re considered rights to you as a customer at the lowest price. This explains the rise of Amazon — and why it is that Amazon, as the central metaphorical and actual business concern, expresses so much of our era. It’s the relentless pursuit of the most discrete desire of the consumer. If you can service that desire, you can have access to every part of the society.

Moyers: So we are customers to the system?

Akhtar: I would say customers to reality.

Moyers: Customers to reality? What does that mean?

Akhtar: Our meaningful agency, our daily raptures, our daily humiliations are wrapped up in purchase. We placate the abstraction that rules us, the economy, with our ritual purchases. I remember walking up Broadway a few years back, this may be 10 or 12 years ago, and I saw a mother and a daughter standing at a shoe store window. It was about 8 p.m., the store was closed. There was nobody else on the street. And I overheard snippets of the conversation as I passed them. I overheard the mother identifying a pair of red shoes that she thought were wonderful. And the daughter — she was 13 or 14 — said, “Oh, Mom, they’re beautiful. How much do you think they are?” And the mom lowered her head to kind of peer underneath to see if she could see the price tag and she saw that they were $300. She said, “Oh my God, they’re so expensive.” And the daughter said, ”Oh, mom, you have to buy them. If you don’t buy them, it’s not good for the economy.” Now that was a fugitive scene I was passing. But at that moment, so much coalesced for me. It was a moment where I really saw to the essence of something that we had become. We are defined by our act of purchase, which is being made ever more free of friction, ever more easy, through these devices and the technologies of the attention-finance complex.

Moyers: The attention-finance complex?

Akhtar: President Eisenhower, as you know, warned us against the predations of the military-industrial complex, which could entwine us in lucrative warmongering from which we would never escape. Well, there’s more money to be made today in the merchandizing of attention than in the merchandising of arms. The Googles, the Facebooks, the Apples, the Twitters are married to the mature practices of finance, that nexus of hidden interests, if you will, that I am calling the attention-finance complex. Technology has become so mature that the very act of these cellphones or smartphones has been to transform consciousness itself into revenue. It’s remarkable how and why this system is so effective because it addresses the pleasure of people so deeply. It’s a neurological thing. These phones, these devices are giving people a dopamine or neurotransmitter return from the simple activity of looking at the screen. This husbandry of our pleasure principle is being yoked and trained to serve ends we do not understand which are ultimately making the distributors wealthy, irrespective of your point of view. What’s really happening? All of our arguments and conversations that are happening on social media are generating revenue. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a white supremacist or a transgender person, a socialist or a libertarian, it’s all creating money for the system.

Moyers: And how do you see this affecting democracy?

Akhtar: I would put the question to you. How do you think it’s affecting democracy?

Moyers: I think it’s turning democracy into a Potemkin’s village set in the middle of a battlefield where war is being waged to define reality and determine the meaning of truth. It’s creating a fraudulent reality in which we think we are equal and we’re not. You may think when you go into the voting booth that you are the equal of Michael Milken or—

Akhtar: Oprah Winfrey, Bill Gates—

Moyers: —but in fact the wealthy buy the rules they want, the returns they want, the rewards they want, while you watch the news.

Akhtar: I once did a deep dive as a student into the politics of the Soviet Union and was astounded at how those people had no understanding that the Party was dictating their worldview. There was no connection between what the Party said and what was real. You could see the Politburo where everyone stands up as if they were a bunch of sheep. That’s what we have come around to with our free-market ideology. We believe all this stuff.

Moyers: And you contend that people without capital are no longer meaningful citizens.

Akhtar: We are free to be outraged, to pursue our desires, as whimsical as they may be, and that is seen as freedom. But our desires have been curated, trained, put to the use of the corporate state, and we are told it’s all sacred, because it’s in the name of individualism.

Moyers: So when you say that people have few opportunities to demonstrate their “surpassing excellence” other than in the making of money?

Akhtar: That’s the way you achieve your American greatness in our era, defined by the accumulation of wealth.

Moyers: Outside of it you are…

Akhtar: Irrelevant. I have known many people in the legal and finance realms, and one of the things that I’m always struck by is the depth of some of these individuals, how thoughtful they are. And yet they are utterly in service to the very values that they are often at odds with. Individual choice becomes the banality of evil. We go along with the system.

Moyers: And where does it end?

Akhtar: I think we are in the process of destroying the world. Contemporary capitalism is predicated on the idea that capital will never be returned to the cycle of decay. It must never be a winter or fall. It must always be the spring and summer of capital. But that’s falsity. Nothing is not returned to the cycle of decay. This contradiction is fueled by debt. The means by which we keep this lie, this fiction alive, is debt. And that is literally eating the planet.

Moyers: Since I saw Junk I’ve been thinking a lot about a line from the movie Green Pastures, based on James Weldon Johnson’s Broadway play in the late 1930s. The angel Gabriel looks down on the world and says to God, “Everything that’s tied down is coming loose.” And he pleads with God to let him blow the trumpet and bring it all to an end. Do you feel the same way?

Akhtar: I do. But I don’t wish the trumpet to be sounded so that everything can be blown away. What I think is that finance and the attention-finance complex have created an illusion of reality with which we’re engaged all the time, and the unfettered rise of individualism has led to the erosion of structures and the collapse of a shared vision of well-being, to the loss of public space, a public personae and public life, and that we are experiencing a rapid atomization of society that has spiritual corollaries.

Moyers: What’s the solution?

Akhtar: Turn off the phone for a week and see how everything starts to feel different.

Moyers: Ayad Akhtar, Thank you.

The play is Junk. It runs through Jan. 7 at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre at Lincoln Center.