The historian Rick Shenkman is editor and publisher of the indispensable website History News Network. I’m a fan and recently had the pleasure of reading his latest book, Political Animals: How Our Stone-age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics.

The historian Rick Shenkman is editor and publisher of the indispensable website History News Network. I’m a fan and recently had the pleasure of reading his latest book, Political Animals: How Our Stone-age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics.

Shenkman himself possesses quite a highly evolved brain, but he nonetheless admits he has his own share of stone-age brain cells. However, there is no club in his hand at the moment, just this book, which frankly, packs all the wallop he needs. If you want to know why this is the year of Trump, you’ve got to read it. If you want to know why millions of Republicans still believe Barack Obama is a Muslim, you’ve got to read it. Even if you want to hold on and remain an optimist, you’ve got to read it.

This week, I sat down with Rick Shenkman to talk about the brain of the American voter, and what is firing its synapses during this extraordinary primary season. Listen to our conversation by clicking on our stream below. You can also download it and take it with you, or scroll down to read the full transcript.

Transcript

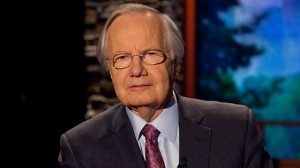

Bill Moyers: Greetings. This is Bill Moyers. And I’m here to see if we can step out of our stone-age brain for a few minutes while we talk about politics. What’s that? You’re insulted? You don’t have a stone-age brain? That’s what you think. As you’re about to hear, part of us is perpetually Pleistocene. Our roots wind back two and a half million years to hairy-faced ancestors with thick hands and short stubby fingers wrapped around big clubs that will carry them from the cave as they head out for another day of hunting and gathering. It’s true, there’s a little bit of the primitive in all of us; and more than a little bit in many of us. And that’s why Rick Shenkman is sitting across from me at this very minute. That’s right, Rick Shenkman, the historian, editor and publisher of the indispensable website History News Network. That’s where I often begin my day, after of course checking in with BillMoyers.com. History News Network is rich in the perspectives of the past that help us see more clearly the politics of the present.

Rick Shenkman is a scholar of the American voter. In 2008 he published a book titled Just How Stupid Are We? Facing the Truth About the American Voter. And now, as another presidential campaign unfolds like a runaway circus parade, his new book couldn’t be more timely. Jot down the title: Political Animals: How Our Stone-Age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics.

Rick Shenkman, welcome to our show.

Shenkman: Thank you, glad to be here.

Moyers: Were you surprised, have you been surprised, that Donald Trump has been so able to play on the fears of the American voter?

Shenkman: No. You know, I was really shocked by the popularity of Bernie Sanders. But when Donald Trump came along down that escalator back in June at Trump Tower and he started talking about the outsider, basically these Mexican immigrants who were coming across the border without proper papers, I thought, this guy has got a chance. I didn’t think he would go all the way. I’m surprised by that. But I was not shocked that he found an audience for his message.

Moyers: True story: Speaking of an audience, I walked into the grocery store yesterday near my apartment. The stock manager sidled up to me in the bread section and said, “What a circus, what a circus,” referring obviously to the New York primary. I had hardly got the words—seriously, I had hardly got the words ‘Donald Trump’ out of my mouth before he interrupted me. “That Trump is something,” he said. “He tells it like it is. And he’s right, you know, both political parties have stacked the deck against guys like me.” Then he paused and he said, “But nobody pays any attention if I say it.” I mean, is that his stone-age brain speaking?

Shenkman: That is his stone-age brain speaking. So the stone-age brain is the brain that developed during the Pleistocene. The Pleistocene is the long ice age, it lasted two and a half million years, and that’s when the human brain was mainly evolving. We’re still evolving as human beings. We haven’t stopped evolving, we’re continuing to evolve. But it was during that period that we mainly evolved. And we evolved to address the problems of hunter-gatherers who lived during that period.

I give a talk on this. I just was up at Sarah Lawrence and talking to a bunch of students and I show them a video clip of a Trump voter who CNN put on the air and she points with both hands to her brain and she says, “Donald Trump is in my brain, he knows what I’m thinking.”

Susan DeLemus, Trump Supporter: I watch the television and my president comes on the TV and he lies to me! I know he’s lying, he lies all the time. I don’t believe any one of them. Not one. I believe Donald. I’m telling you. He says what I’m thinking!

He actually doesn’t know what you’re thinking, he knows what you’re feeling, and that’s what an awful lot of politics is. When a politician talks anger and they talk fear, they are mainlining, just like a heroin addict, going straight for the most sensitive parts of the brain because fear and anger are those emotions that we really relate to. And when a politician engages and indulges people’s fears and their angers, they seem really authentic. That’s why Donald Trump seems so authentic to so many millions of people because these emotions are so strong and powerful.

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump speaks at a campaign rally on April 11, 2016 in Albany, New York. (Photo by Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/Getty Images)

Moyers: Why are anger and fear so paramount in the stone-age brain?

Shenkman: For people who were very sensitive to anger and fear, apparently, our evolution proves it, that was a habit of thinking that contributed to their survival, to their fitness.

Moyers: They’ll take more precautions than somebody who doesn’t hear the alarm go off, right?

Shenkman: Exactly. There is something called the false alarm bias. What happens is our brains are like good detectors in your home that are looking for gas or for something else, some sign of fire—

Moyers: Carbon monoxide.

Shenkman: Exactly.

Moyers: Burglars.

Shenkman: Exactly, burglars. They’re on a hair-trigger alert. They just detect a little bit and all of a sudden they start blaring. Well, our brain comes with a similar mechanism and that is to help protect us from danger. So the people who are going to be more likely to survive a dangerous attack were those who would be able to be sensitive to when a dangerous attack was coming.

— Rick Shenkman

When Donald Trump is attacking Mexican immigrants or Muslims just trying to come visit the United States, he is activating this deep-seated cognitive bias that we have, which is the false alarm bias. We want to make sure that we respond to a fire alarm. And if it’s a false alarm, that’s okay, because the fire alarm goes off, everybody gets excited, they go out on the sidewalk and then they come back in five minutes later. So, meh, it’s okay. But if you miss a fire alarm, oh my gosh, you’re really, really in trouble. We’ve got this bias that basically says we’re going to react to the fire alarm, even if we’re going to err on the side of better be safe than sorry.

And when Donald Trump and these other politicians activate that bias, what happens is it swamps critical thinking. We have higher order cognitive functions and we are able to evaluate the world as it is and not give in and surrender to these automatic responses. But when a politician activates that response, it’s very, very, difficult in the moment to think clearly. And that’s what these politicians are doing.

Moyers: Sometimes the alarm is for real.

Shenkman: Yes.

Moyers: Sometimes there really is a burglar in the house or the carbon monoxide is seeping under the door. And there are times when Donald Trump is telling the truth, right? I mean this guy in the grocery store was right, the two major parties have stacked the deck against guys like him. So that truth has gotten through the fog of deception. Is that because it’s a truth that they have experienced, that they are right now experiencing a system that has screwed them, and so therefore they believe Trump?

Shenkman: Yes. Exactly. So there’s something that the social scientists refer to as perceptual salience, and basically what that means is that we respond to the signals in the environment that we’re familiar with. So anytime we hear some evidence of something in our own experience, or we’re seeing it on the news constantly, that becomes part of our social reality. And we live in that soup of all these mixed signals out there. And what Donald Trump is doing when he’s saying the political parties are corrupt, as soon as he says it, it’s politically salient because we’ve all heard evidence of the corruption of the two major parties and how they managed to get themselves elected; or to elect their people; and how rich people contribute money to the campaigns; and the corruption, and all that. That’s salient because we hear all about it. So all a politician has to do is touch that button and one of his supporters will say, “Oh, yes.” So it rings true.

Moyers: It’s also true, isn’t it, that we don’t like cognitive dissonance—that when we get these storms in our head, we get stressful and perturbed, and we want to run from them? So cognitive dissonance is something that we want to get rid of as soon as we experience it and, if we feel it, we turn away.

Shenkman: Sure and this helps explain why millions of people still believe that Barack Obama is a Muslim born in Kenya. It’s incredible to any thinking person that anybody could believe that, but these people aren’t thinking, they are reacting.

Moyers: Reacting to?

Shenkman: Well, in their small circle, they’re hearing from people suspicions about Barack Obama: Is he really an American? Isn’t he really a Muslim underneath it all and wasn’t he born in Kenya? And they hear that and that plays into a narrative, a metanarrative, a metacognition that resonates with them. And they piece together all of these little bits of evidence that contribute to their feeling that he’s not really entitled to be president of the United States, whether it’s because he’s black or because he’s too liberal or whatever it is. So they create this metanarrative in their head and everything that is consistent with that metanarrative, they wind up believing. And everything that is inconsistent with it—that would give them cognitive dissonance if they were to try to hold that thought in mind in addition to the other thoughts—they get rid of. They get rid of it.

Moyers: I understand that, I would understand that better if you were talking about a thimble-full of voters. But as you point out in Political Animals, 43 percent of Republicans believe that about Barack Obama; that he is a Muslim not born in America.

Shenkman: Yeah.

Moyers: That’s a lot of people.

Shenkman: That’s a lot of people. It’s millions and millions of people. So eight years ago I wrote a book called Just How Stupid Are We? as you mentioned. I was appalled by the statistics coming out during the Bush years that so many millions of people thought that we were invading Iraq out of revenge because Saddam Hussein had something important to do with 9/11. Now there was no truth to that, but if we can’t get the most basic facts right about the most important event of our time, 9/11, that says our democracy is in trouble. I went around the country trying to scream, “Hey, we have a 10-alarm fire, we have a 10-alarm fire!” But I really did not get the attention of the media. Then Donald Trump came along and now everybody’s saying, “Well, we have a 10-alarm fire.” OK, great, I no longer am Cassandra shouting to the winds. People are paying attention to this problem. It’s a very serious problem.

Moyers: Is it true that the warning we were talking about doesn’t work if the person speaking believes his or her own lies?

Shenkman: This is the key. When a politician, just like a used car salesman, believes their own lies — and most of the time they believe what they’re saying — then our natural defense mechanism, our natural McAfee for the brain, as I call it, goes into somnolence. It goes to sleep.

Moyers: To sleep.

Shenkman: Right. We need to feel that somebody is lying to us for our cheater detection system to work. We’ve got to, on some level, conscious and unconscious, sense that they’re twitching; their voice is going higher; they’re being a little bit nervous in what they’re saying. If they’re not giving off those signals, we believe what they’re saying. Unless we have access to contrary information that will help us say, “Oh, wait a minute. What he’s saying is different. It’s adverse to what I know to be true.” Then that creates some dissonance, and then we have to deal with that.

Moyers: How do we know if the liar believes he’s telling the truth?

Shenkman: Well, it goes back to this perceptual salience. So everything we know about a person, we bring all that information to bear when we’re making an assessment about who they are. And if what they’re telling us about who they are is adverse to what all that other information says, well then there’s a conflict and now you’re forcing the voter to have to make a choice between what they know and what you’re telling them. And you know what? They are going to go with what they know. We privilege information that we already believe to be true. And when we hear contrary information to that, boy, that’s a high hurdle for it to make before we’ll change our opinion.

Moyers: This partisan brain you talk about— I say, ‘Ouch,’ when you say that, because none of us likes to think we have a partisan brain, particularly journalists. We like to think we have a nonpartisan, or at least a bipartisan brain. But Trump’s voters, have they not been ridiculed for their willingness to overlook his inconsistencies? And isn’t that what all voters do once they’ve become committed to a particular candidate?

— Rick Shenkman

Shenkman: Exactly. When I was a college student at Vassar, I was a conservative back then, and I was a true blue conservative supporter of Richard Nixon. So I was there during the years of Watergate. And I stuck by him almost until the end, only two months before he finally resigned, I was one of those dumb 23 percent who still believed that guy’s lies right up until almost near the end. And why was that? I was paying attention. I was reading the paper. I was watching the Watergate hearings. The next day I would read in the newspaper the transcripts. I was studying this stuff, and still I stuck by Richard Nixon. It makes no sense in retrospect. I thought I was being a thinking voter, but I was actually not. I was using what Daniel Kahneman calls “system one thinking.” I was just reacting. I wasn’t using higher order cognitive thinking, which is “system two thinking,” where I sit back and I question my own assumptions. That’s what voters need to do — second-guess our automatic reactions. That’s the main theme of the book. Don’t trust your instincts.

Moyers: You were not alone, because after Watergate, after the scandal broke, after all the exposés, after millions of people knew that Richard Nixon was a crook — he was reelected. What’s at work there?

Shenkman: Once we commit to a candidate, we become engaged with that candidate, and we’re no longer defending the candidate. We’re defending our vote for that candidate. So once we make a commitment to a politician, it is very difficult for us to change our minds about the politician, because it’s no longer about the politician. At that point, it’s about us. Politics in the end is always about the voters. It’s not about the politicians. The media, I think, make a mistake in constantly talking about the politicians as if that’s what matters in an election. That’s not what matters. What matters is the voters’ response.

Moyers: My friend Mike Lofgren spent over 30 years as a top congressional staff member — a Republican, by the way, a career civil servant in Congress. He made the point recently that while the Washington establishment dismisses Donald Trump as a buffoon who doesn’t understand the intricacies of national security policies, some of what Trump says underscores how foolish those policies are. He’s been calling out the Democratic and Republican strategy in foreign policy and national security for the last many years and the elites can’t stand that this buffoon is exposing the folly of their strategies. Any truth to that?

Shenkman: Absolutely there’s truth. Trump, in the middle of one of these incredible circus GOP debates, said that George W. Bush didn’t keep us safe. And, oh my gosh, the reaction of the crowd was just hostile. Well, that’s true, right? He didn’t keep us safe. 9/11 happened while — it was on his watch. So that was Donald Trump saying something that no Republican wanted to hear and that Barak Obama never even said as president or as a candidate. He didn’t want to go there. Here was Donald Trump actually telling the truth about something and it was a taboo. The elite didn’t want to go there. They didn’t want to break this mystique. Obama for his own reasons, he wanted to be the president who brought us together and if he brought us together, he couldn’t do it after roasting the previous incumbent administration for 9/11. Nobody wanted to talk the truth. So we can thank Donald Trump for a few truths.

Moyers: Where you do you see the stone-age brain at work in the candidacies of Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders?

— Rick Shenkman

Shenkman: Well, I think that their voters, while they’re primarily not the low-information voters that Donald Trump is drawing, they’re also making assumptions about these candidates that are favorable to the opinion that they previously had arrived at about these candidates. So the Bernie Sanders people aren’t bothered, for instances, about the interview that he gave with the Daily News editorial board, where he seemed a little spotty in his answers to questions that are fundamental to his campaign. The same with Hillary Clinton supporters, they seem like they’re not paying too much attention to this whole email mess. They have a million excuses for why it’s not really a big deal and maybe it will turn out to not be a big deal. But we all have the capacity as voters to try to rationalize for our candidates what they have done. But we all have the capacity as voters to try to rationalize for our candidates what they have done. And it’s because, in the end, it’s not about them; it’s about the choices that we previously made. Once you as a voter make a choice for a candidate, you will then act as their spinner. You are spinning and spinning just like you were on the campaign staff.

Moyers: What’s the best hand to hold in this game? A fistful of cards that offer hope, or a fistful of cards that produce anger? Which is the greater motivator — fear or hope?

Shenkman: Fear and anger connect with people much more viscerally than hope does. Now if all the stars aligned, a guy with a hopeful message, like Barack Obama eight years ago, is able to triumph. But we’re living in a period right now where a lot of the problems from ’08 haven’t been solved and people feel like the crooks never faced their comeuppance. We see constantly on television evidence before our eyes of Muslim extremists blowing stuff up. It’s very disconcerting. In this period of high vulnerability, we are much more likely to be susceptible to an unthinking, automatic favorable response to a fear or anger message.

Now here’s the problem, where it gets complicated. When Martin Luther King was organizing marches in the 1950s, he had to count on people getting angry about Bull Conner unleashing those mad dogs on protesters down in the South. But he was leading a minority movement. A minority movement—whether it was the Civil Rights Movement in the ‘50s and ‘60s, or Act Up for gay people protesting the negligence towards AIDS victims in the 1980s — for those people, they need anger to create energy and social cohesion for their group, as they’re facing incredible odds. But, when a majority of the voters are angry, we can’t think straight. It’s not good.

Democracy doesn’t work if everybody’s angry at everybody, because anger literally stops us from wanting to compromise. Anger emanates primarily from the insula in the brain. And when the insula is activated, we don’t compromise. When we are anxious, which is the amygdala part of the brain, that’s okay. We can be anxious about stuff and we’ll still be willing to compromise. But when we go toward this dark anger, and a majority do, everything stops and that’s really my diagnosis of why the country is in so much trouble right now.

Moyers: Can a democracy die of too many lies?

— Rick Shenkman

Shenkman: Well, this is an experiment in which we are guinea pigs. Through most of American history, Americans trusted their leaders and their primary institutions. And then, beginning in the 1960s, between Vietnam and then Watergate, and Iran-Contra and the inflation of the 1970s, all of that together really assaulted our sense of trust. In the early 1960s, before all that happened, trust was at a level of somewhere like 70 percent. If you asked the average American, “Do you trust that that the president, most of the time, is going to do what’s right for the country,” 70 percent of Americans said yes. Now it’s like 20, 25 percent. You see these low trust figures for both Trump and for Hillary. It’s just appalling. Can a democracy work if people don’t trust the major players and the major institutions? Who knows? We’re going to find out. Mass democracy is not but a couple hundred years old. It’s an experiment we’re on.

Moyers: You probably don’t believe that history repeats itself, but I know it keeps knocking on the same door from time to time. And as you talk I’m thinking we’re up on the 50th year of Lyndon Johnson’s departure from the presidency in 1968, humiliated, disgraced, disillusioned. I think some of the audience, as you know, know that I worked the first and middle years of that administration and then left in ’67. I was not around in ’68 when he played with the idea of running again.

Lyndon Johnson was a president whose credibility kept sinking. He kept saying the war could be won, the war will be won, there’s light at the end of the tunnel. And facts on the ground proved him wrong. So that by the early part of ’68, the perception of LBJ was of a chronic liar, a man who was deceiving the country. Now in retrospect, and at the time, I think he believed the war could be won. I really do. I really think he thought the war would be won. And he kept pressing on until it was too late to realize he was wrong. Are there other presidents in our history who have been brought down by the perception of lying just as Lyndon Johnson was?

Shenkman: It’s interesting, some presidents are brought down by it and some totally escape it. So just as a point of contrast, let’s talk about Grover Cleveland. Grover Cleveland in the 19th century was a Democrat who got elected in the shortest timeline of any president in our history. He went from being the sheriff of Erie County, to the governor of New York, to president of the United States, in three years. That’s a remarkable — people think that Barack Obama came from out of nowhere; Grover Cleveland came from out of nowhere. Why? Well, because it was the Gilded Age. Politics was so corrupt, the American people were willing to try the presidency on anybody as long as they seemed to be honest. So his nickname was Honest Grover.

He gets into office and what happens? He’s a fairly middle-of-the-road president, kind of a conservative Democrat. He winds up winning the popular vote for reelection but losing the Electoral College. He goes away for four years. He then comes back for the next term. Right after he’s taking office in his next term, all of a sudden, he discovers cancer — cancer of the jaw. He has to undergo an emergency operation and he creates this elaborate lie saying that he’s going on summer vacation and he’s going to be out of touch with the media, and with everybody, for a couple of months. And he goes off to Cape Cod to recover. He has this operation actually out on a yacht in the ocean, where nobody else can see it, or hear about it. And he puts his people out to lie — to absolutely lie.

After he comes back to the presidency, reporters were kind of suspicious. They didn’t buy this argument that he had just disappeared for a couple of months and everything was fine. They were suspicious. Some of them even said, “Does he have cancer?” Even back then, the big C word. But he put his people out; they told the lie, and the lie held. It held even after a Philadelphia paper published the truth on the front page. The public had ingrained in their head that Grover was “Honest Grover Cleveland.” And because not enough evidence came out that he was guilty of lying about this, and this, and this, and this, and this, he was able to get away with his lies. And to this day, most people don’t know this story. I’m fascinated by it. He got away with it.

So why didn’t Lyndon Johnson get away with his lies but Grover Cleveland got away with his? Well, because one of the ways that we track people — and this is part of our cheater detection system — is that we can pay attention to people’s reputation. Cleveland basically had a reputation that he was honest and LBJ had a reputation, following him all the way from his Senate days, that maybe he’s not totally trustworthy. And that’s what led to his undoing.

Moyers: Landslide Lyndon.

Shenkman: Landslide Lyndon from ’48.

Moyers: Do you recall how Lyndon Johnson was reviled for being crude and vulgar when he showed the scar of his gall bladder operation to the public? Pulled it back on the grounds of Bethesda Hospital?

Shenkman: It was an incredible moment.

Moyers: It was incredible. You know why he did that? He did that because we knew that people were circulating that he had cancer; that he was in more trouble than we had said he was. And then he just said, “By God, I will show them.” So he pulled back his gown and there was the scar, which ultimately became the map of Vietnam in the hands of the cartoonists. But that was because, long after Grover Cleveland, he wanted people to know he was telling the truth, he really wasn’t suffering from cancer.

Shenkman: Well, here’s what’s interesting to me as a historian. I wrote a book called Presidential Ambition, and one of the things I was doing was tracking presidents lying. Almost all of them lied, except for George Washington, because he was handed power on a platter. He won the Electoral College unanimously, OK? None of his successors have. All of them have been under such pressure cooker pressure that they wound up lying, fudging the truth, compromising their principles, selling out friends, sacrificing people who were supporters, all of this horrible stuff.

But here’s the interesting thing. With these presidents, we find that they are telling the truth as they see it convenient for them. And there’s one issue though that they will lie about the most. It’s their health, to bring it back to LBJ and his scar. It’s their health. That’s what they lie about the most, because it’s personal. I think it’s really helpful to think about politicians as primates. No alpha primate wants to ever let the primates below him, with lower status, know that he is ill. That’s what our presidents do.

— Bill Moyers

The fact that Lyndon Johnson was worried about a president being called on the carpet for telling a lie about his health, well, of course his immediate predecessor, Jack Kennedy, had lied tremendously about his own health. He had Addison’s disease. It was a terribly crippling illness. He probably couldn’t have survived a full two terms, if he had lived and hadn’t been assassinated, because of this illness. He was being shot full of drugs every day just to be able to get up out of bed. But he wasn’t going to allow that for two reasons: One, if you’re the dominant politician, you want to be able to say, “I’m healthy.” That contributes to this aura of dominance. But, two, you want to be able to control the national conversation. And if you’re sick, all of a sudden, all anybody’s going to want to talk about is that you’re sick.

Moyers: When I was the press secretary at the White House, I once asked the great reporter in Vietnam, David Halberstam, who’s telling the truth out there? And David thought a moment and replied, “Everybody.” Everybody sees what is happening through the lens of their own experience. Do we ever get to the truth if we do that?

Shenkman: I’m a historian, right? People who aren’t historians think that you go look up the truth in a history book and that’s it. But if you ask any professional historian, they will tell you that every generation rewrites the history books, because history is, as Richard Curran said, an argument without end. That’s what history is all about. There is no way to consult the gods on Mount Olympus and say, you know, “Give us the truth of what really happened.”

We think the voters want the truth. The voters don’t want the truth any more than you and I want the truth. You and I don’t want to be told some truth that makes us uncomfortable about ourselves. The voters don’t want to be told some truth that makes them uncomfortable about their choices. And that’s why myths are so powerful. These are metanarratives that help explain who we are and what values we cherish. And they are mostly what elections wind up being about. We’re not really trying to decide the truth in elections. We’re trying to decide which candidate’s myth we prefer. And that’s easy, that’s much easier than trying to decide what the facts are.

Moyers: Do you believe facts matter anymore?

Shenkman: I love facts. But I am not so self-deluded as to believe that the myths in the end don’t trump the facts. The myths, just like beliefs, trump the facts. For instance: The myth that Ronald Reagan won the Cold War. That’s been dissected 20 times over from every angle, on the left and the right, and the thoughtful people say, “Okay, he did not singlehandedly win the Cold War. Maybe the Pope played a role. Maybe—”

Moyers: —Gorbachev played a role.

Shenkman: “—Gorbachev played a role. Maybe the price of oil declining and bankrupting the country of the Soviet Union, that played a role.” All kinds of people played a role. Truman played a role in setting up the Cold War national security apparatus that we put to use for 40 years in battling the Soviet Union during the Cold War, so lots of factors. And as a historian, I love complexity. I don’t like these single answer solutions. But for the American people, Ronald Reagan won the Cold War. That’s a myth. That helps them understand the world. That’s what these myths do. The world is a very complicated place. We want something that’s simple.

Moyers: Al Gore learned that when he tried to confront the American people with the inconvenient truth of global warming, of climate change. And what he discovered is that billions of people simply dismissed it, and were so affronted by it, that they became ardent opponents of the whole idea of global warming and climate change.

Shenkman: Yes. Historians like to play the “What if?” game. My “What if?” game is—if only Al Gore had been president in 2000, instead of George Bush winning the presidency, what a different world we would be living in.

Moyers: Speaking of the year 2000, when George W. Bush beat Al Gore, you claim that George W. Bush won in part, particularly in Florida, because of a severe drought. Right? Talk about that.

Shenkman: I open the book with the research by Larry Bartels and Chris Achen. They are two of the most preeminent social scientists in America, and they did research showing that droughts and flood have affected the outcome of up to a dozen presidential elections in the last hundred years. They went back from 1896 all the way to 2000. And they found that the weather actually affects the outcome; it can move the needle by one or two percent. Well, in a lot of these close elections, that can be enough.

And in Florida they were having a severe drought that was affecting the election. They do these regression analyses that show by historic measures Gore should have won by X number of votes. And in fact, he wasn’t winning and where was he not winning? He was not winning in the counties he should have won in by historical projections where the drought was most severe. That was northern Florida. What does that tell you? That tells you that voting is in part an irrational act and we delude ourselves in thinking that we’re rational creatures. We’re emotional creatures, we respond to things. When bad things happen to us that have nothing to do with politics, like bad weather, a drought or a flood, we want to take it out on the incumbent. And this is true of people all over the world. It’s something that’s embedded in human nature.

Moyers: That we blame the incumbent for the act of God.

Shenkman: Yes.

Moyers: There’s something else going on that intrigues me, and I wanted to ask you about. One of your historian colleagues, Heather Cox at Boston College, recently wrote an article about how wealthy, white elites protect themselves. And I thought about this in reference to my friend at the grocery store who was saying, “Trump is right, the two parties have collaborated and they’ve ganged up on me, and people like me.” Donald Trump, who’s not known for being a polite competitor. He’s known for being ruthless, for the art the deal, for firing people in prime time. And yet this fellow thinks that Donald Trump, this ruffian billionaire, he’s going to protect his financial interests. And he sounded like he’s going to vote for Trump on that basis. Is that the stone-age brain speaking to us?

— Rick Shenkman

Shenkman: I believe that is the stone-age brain speaking to us. A voter, his feeling, his nervous system — that’s what we’re talking about, his nervous system—is getting angst. He’s having anxious moments over what seems to be happening. In the soup of information that he is living in, he’s getting negative signals. Trump is connecting with that negative signal and he’s saying, “I’ve got a solution.” He doesn’t spell out exactly how his solutions, building a wall, excluding Muslims, is going to help this guy and his family do better in the world, but somehow because Trump is rich and powerful and he’s been a known quantity for years — he’s familiar — all of a sudden, the guy says, “I want to defer to him. I think he’ll know how to get us out of this situation.” Because, at least, Trump is dealing with something real in that guy’s world. Whereas a lot of the other politicians, Hillary Clinton, she’s really got this problem: It is not clear when somebody votes for Hillary Clinton what emotion they’re supposed to be feeling. We know what a Donald Trump voter is feeling. We know what a Bernie Sanders voter is feeling. It’s not clear what a Hillary Clinton voter is supposed to be feeling. And the election, in the end, is always about the voter. She’s made the campaign about herself. She has not made it about her voters. Until she figures that out, she’s going to struggle.

Moyers: Is it conceivable to you that if Trump were not misogynist, if he were not racist, if he were not speaking crudities the way he does, if he were not so seemingly perpetually a liar — otherwise — he’d be a hell of a candidate right now, in this time, when there’s so much disillusion with elites, with the establishment, with the economy, with what’s happening to everyday people?

Shenkman: If Donald Trump had more self-discipline, I’d say he’d be well on his way to being the next President of the United States. That’s all it would’ve taken was self-discipline. He still could have made his appeals to people’s anger, but he wasn’t self-disciplined enough. And Teddy White gives us the reason for that.

Moyers: The late reporter who wrote several volumes on American presidential candidates.

Shenkman: Exactly. In one of those books, he said that presidents get into office and they think, “Wow, I’m president of the United States. I must have gotten here because of who I am and how I operate.” They read into their success a lesson, and the lesson is, “I should continue to operate the same way I have been operating, because it got me to the most powerful job in the world.” Donald Trump got to where he was by saying misogynistic things and xenophobic things and all this other stuff, and telling lies. He got to where he is in the GOP primary campaign by saying these things. He’s now learning — he’s only been in politics for a little while — but he’s learning the lesson that, “Oh, this worked, this worked, this worked.” And even though he’s being told now he’s got to change, he’s got to pivot, and good presidents know that they have to pivot, he is instinctively saying, “But I got to where I am by being me.”

Moyers: And there certainly is a backlash. Lies are like boomerangs. They can come back and decapitate the person who throws them out there. There was a story in The New York Times recently, “A barrage of attack ads threatens to undermine Donald Trump.” And the reporters go on to say there’s evidence that the negative ads still work and that they are beginning to take a toll on Trump because, according to one Republican strategist, “The best way to go after Trump is to use the bombastic billionaire’s own words against him.” And they’re doing that now. If you look at these ads running right now in the New York markets, because of the primary coming up next Tuesday, they’re all relentlessly negative about Trump but they’re throwing back at him, like boomerangs, his own language, his own words.

Shenkman: That’s, heaven help us, one of the things that might save us from a Trump presidency. I wrote the book not thinking that I would have a hopeful message at the end, and then the more I read the scientific literature, the more I became convinced there are real strong grounds for optimism. And here’s the primary reason: because every human being comes equipped with a mechanism that creates anxiety when the real world comes into strong conflict with their beliefs. When we, over time, become convinced that something in the outside world is at variance with what we believe about the world, then we become anxious and that opens our mind to change. We are not just partisan voters. We don’t just have a partisan brain that makes us stuck forever with a bad candidate or a bad system or bad politics. We can change when we become anxious. When we start getting that little niggling feeling that, “Oh something seems wrong here, I need to investigate it.”

Moyers: The book is Political Animals: How Our Stone-age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics. Rick Shenkman, thank you very much for being with me.

Shenkman: Thank you Bill.