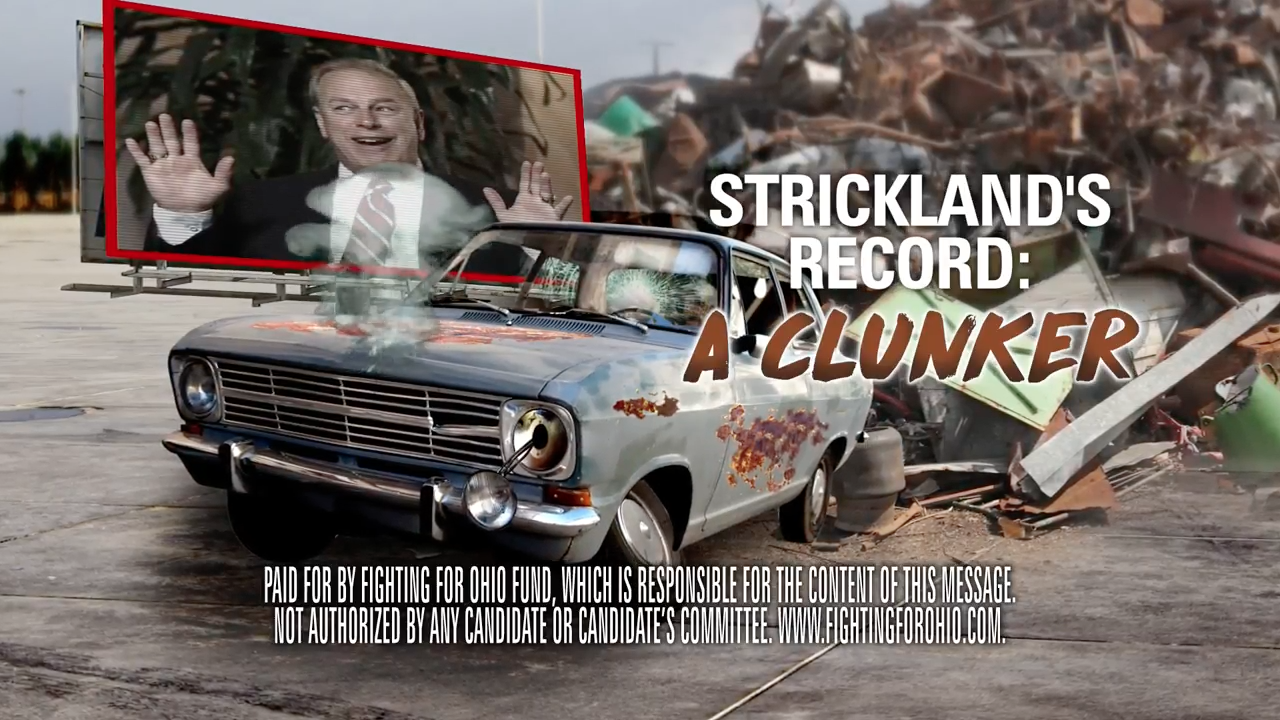

A still from an ad attacking former Ohio governor and Democratic US Senate candidate Ted Strickland. FIghting for Ohio, the group behind the ad, refused to provide info about its executives to a television station with which it purchased an ad, according to a new report by the Campaign Legal Center. (YouTube)

Transparency advocates thought they had scored a victory back in 2012 when the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ordered television stations to start posting online contract information about the political ads on their airwaves. The original mandate, which affected only stations in the top 50 markets, has since been expanded to include all broadcasters, cable outlets and radio stations.

These disclosures can provide valuable information about efforts to influence the election, most notably the identity of the persons behind vaguely named “dark money” groups that don’t have to disclose to the Federal Election Commission.

But there’s a problem: Stations are accepting incomplete or inaccurate forms from the advertisers. They’re posting “disclosure” forms that sometimes don’t disclose much: Often they don’t have the information the law requires, and that is critical for the public to understand who is trying to affect an election. In some cases, disclosures are only partially complete. In other cases, advertisers aren’t cooperating but stations are running the ads anyway.

Of 1,220 disclosures to the FCC made by television stations in battleground states, only 65 percent were complete, and many were inaccurate, according to a new analysis by the Campaign Legal Center. The group is filing a complaint with the FCC today, asking the agency to do something about this flouting of its own rules.

Among other omissions, the group found that stations are letting political organizations place ads without providing names of the people behind the often ambiguously named groups. If an ad pertains to “a political matter of national importance,” the FCC requires stations to obtain names of executives or board members of the organization making the buy. But often, advertisers claim their ad does not clear that bar — even when it obviously does. Other times, advertisers provide the name of a middleman — someone at an agency who purchased the ad on their behalf — but avoid naming anyone involved with the organization that actually created the ad.

The Campaign Legal Center found, for example, that several television stations in Wisconsin, including ABC, CBS and Fox affiliates, broadcast ads by the Chamber of Commerce supporting incumbent Republican Sen. Ron Johnson. But the group claimed its ads were not of national importance, and the television stations, it seems, were happy enough to not challenge that assertion, take the money and run — even though Johnson is running for a federal office in a contest that could determine which party controls the US Senate next year.

The effects of failing to comply with seeming legal technicalities can be profound. When stations fail to document this information in the forms they submit to the public via the FCC’s website, they make it easier for special interests to anonymously influence an election’s outcome. Whether an innocuously named group recommending a lawmaker’s environmental record is backed by an environmental group or an industry trade association, for instance, might make a difference to how voters interpret the information.

The Campaign Legal Center also highlighted a station that did try to do the right thing, up to a point — an NBC affiliate, WLWT, in Cincinnati, Ohio. But when WLWT pushed super PACs buying ads on its airwaves to give the names of their executives, the groups simply refused. And with that, the station’s responsibility was done. The FCC only requires that the stations “use reasonable diligence” to get names from advertisers. If the advertisers refuse in the face of that diligence, the ad can still air.

Another issue that complicates these disclosures: Broadcasters aren’t required to use a standard form. “When you look at all these different forms, it’s very hard to make a comparison. It’s apples and oranges,” said Meredith McGehee, Policy Director of the Campaign Legal Center. Her organization, she said, would like to see the FCC order stations to use one standard form.

Better yet, McGehee said, the FCC could require groups that buy political ads to disclose not just their executive membership, but the source of their funding. Just as political candidates say at the end of advertisements that they “approve this message,” billionaires and corporations — many of whom fund political campaign advertising by channeling it through nonprofit groups and LLCs with anodyne names like “Fighting for Ohio” — would also have to make their names publicly known.

Advocates aren’t sure how likely it is the FCC will take action to move disclosure toward this final, ideal scenario. Tom Wheeler, the head of the FCC, made it known before taking the helm of the agency that donor disclosure would not be a priority.

The reason why goes back to the efforts by Wheeler to get confirmed. Ted Cruz, a Texas senator and former Republican presidential candidate, had put a hold Wheeler’s nomination in the Senate. The hold was lifted after a private meeting between the two men, following which Cruz issued a statement declaring Wheeler “explicitly stated” that using FCC authority to require donor disclosure was “‘not a priority.’”