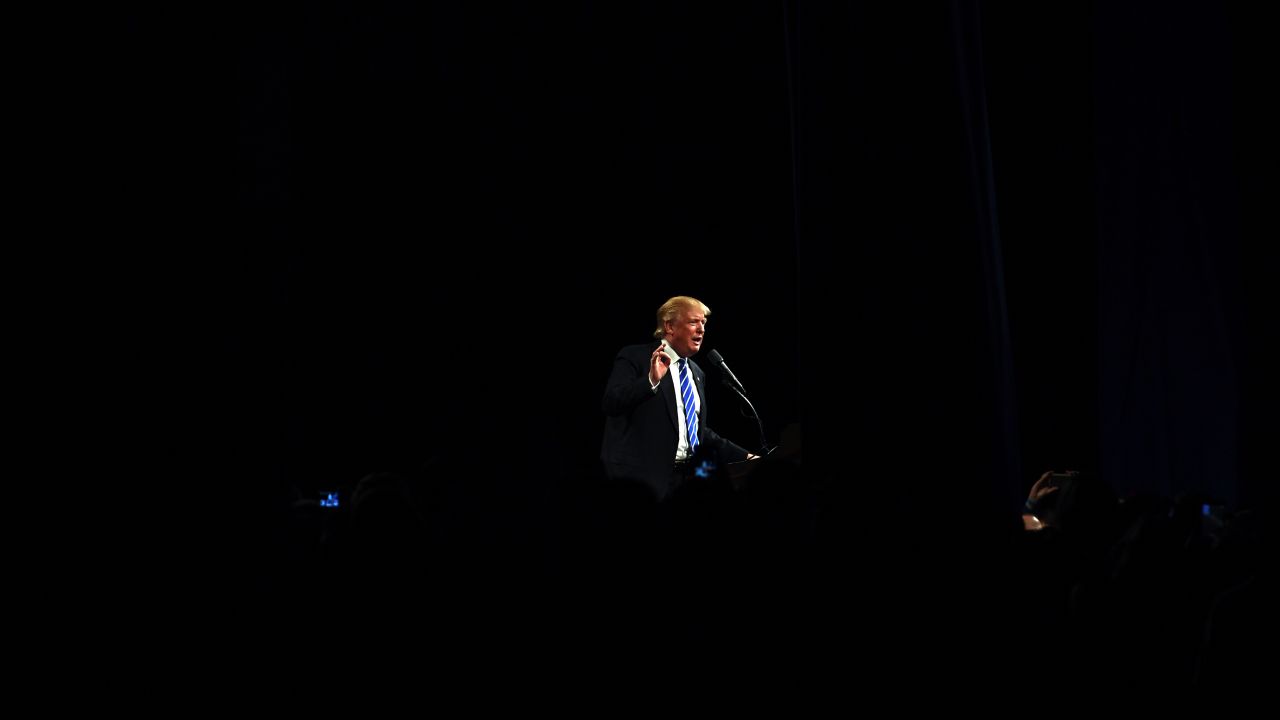

Donald Trump speaks during a campaign rally at the Suburban Collection Showplace in Novi, Michigan, on Sept. 30, 2016. (Photo by Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images)

The European Union on Tuesday voted to opt in to the Paris climate agreement, paving the way for the historic global pact to go into effect next month. That means this first US-backed international effort to keep climate change under control will enter into force right around the time the US will elect its next president.

The Paris agreement itself is not enough to ward off climate change, but it lays the groundwork for a future, more aggressive deal. Diplomats have been struggling to get an agreement like this one in place for more than two decades, and only now, with the world rapidly approaching critical climate tipping points, is it finally going to become a reality.

Unfortunately for the planet, just as the deal’s existence hinged on the US’ willingness to come to the table, its future success will hinge on what American voters decide on Election Day.

As environmental groups frantically have been trying to point out, Hillary Clinton would build on President Barack Obama’s efforts to reduce the nation’s contributions to the climate change problem. In contrast, Donald Trump, advised by oil executives and with policies drawn wholesale from think tanks that are funded by the fossil fuel industry, has made it clear he intends to move the US quickly and decisively in the opposite direction.

This very expensive GLOBAL WARMING bullshit has got to stop. Our planet is freezing, record low temps,and our GW scientists are stuck in ice

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) Jan. 2, 2014

A potential President Trump easily could undo years of hard work and trust-building. It would be within his power to simply pull out of the climate deal — and all other future UN climate negotiations — during his first year in office, writes Climate Central reporter John Upton. Moreover, a Trump administration could unwind policies the Obama administration put in place to meet its promise to cut emissions.

The Obama administration’s pledge, made first to China in November 2014 and then to the world in Paris last December, is that the US will, by the year 2025, reduce its emissions by at least 26 percent from 2005 levels. To hit this target, Obama ordered the EPA to put in place regulations to, for example, reduce the amount of pollution that comes from America’s power plants and raise fuel efficiency standards for vehicles. Faced with a recalcitrant Congress, Obama had to resort to executive orders to get the new laws in place.

The problem, however, is that executive orders are very easy to undo. And that’s a fact, Evan Osnos reports in a recent New Yorker article, that Donald Trump’s advisors are very aware of.

Trump aides are organizing what one Republican close to the campaign calls the First Day Project. “Trump spends several hours signing papers — and erases the Obama presidency,” he said. Stephen Moore, an official campaign adviser who is a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation, explained, “We want to identify maybe 25 executive orders that Trump could sign literally the first day in office.” The idea is inspired by Reagan’s first week in the White House, in which he took steps to deregulate energy prices, as he had promised during his campaign. Trump’s transition team is identifying executive orders issued by Obama which can be undone. “That’s a problem I don’t think the left really understood about executive orders,” Moore said. “If you govern by executive orders, then the next president can come in and overturn them.”

In short, much of Obama’s climate legacy could be wiped out with the stroke of a pen. If the second-highest-polluting nation in the world were to ignore the Paris agreement and give up on its attempts to cut emissions, other countries would have little incentive to stick to their own commitments. An international deal — decades in the making, struck by 200 countries — could be undone quickly by the leader of a single country.

While China now ranks No. 1 overall in greenhouse gas emissions, the US, in second place, emits far more per capita. History shows that if the US were to decide not to play ball, the agreement would become meaningless; the earlier Kyoto Protocol ultimately resulted in little progress after former President George W. Bush pulled the US out of it.

It took a huge amount of work to get the process back on track. UN bodies have fought for years to get all the world’s nations on the same page on how to go about cutting emissions. Until 2014, it looked unlikely that the US and countries with developing industrial economies would ever see eye-to-eye. But that year, US Secretary of State John Kerry announced a bilateral deal with China under which both countries would cut their emissions. Once the top two greenhouse gas emitters signaled they were ready to change their ways, diplomats were able move ahead with a global accord.

After an agreement was reached last December, each of the 191 countries that helped write it had to formally opt in. The deal would go into effect when 55 countries representing 55 percent of global emissions agreed to participate. The process of inking those agreements has been underway over the course of this year. Both China and the US opted in early last month. Obama’s diplomats had pushed hard in Paris to make sure the deal was constructed in such a way that the president would be allowed, under US law, to opt in without consulting Congress.

By the time heads of state convened for their annual September meeting at the UN’s headquarters in New York this year, 60 countries representing 48 percent of global emissions had signed on to the deal. “What once seemed impossible now appears inevitable,” Secretary General Ban Ki-moon said. This past Sunday, India, the world’s fourth-largest polluter (if you count the EU as a single entity) opted in. And the EU’s vote Tuesday marks the tipping point. Now, governments responsible for the majority of global emissions (China, the US, the EU and India are alone responsible for 60 percent) have joined the deal, moving the number of countries on board past that 55-percent-of-emitters threshold. Thirty days from now, it takes effect.

Even under the Paris agreement, countries will not cut emissions dramatically enough to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the point at which scientists say climate change will become much more dangerous, and far harder to reverse. To hit that goal, nations will have to continue to work together to improve their pollution-cutting performance beyond what they initially committed to under the Paris deal — something that diplomats behind the deal openly acknowledged last December.

But the agreement is going into effect not a moment too soon, in the view of experts who track the effects of global warming. The storm that lingered over Louisiana for days this summer, dumping rain, causing floods and rendering thousands homeless, is one example of weather events that scientists have linked to the changes underway.

But though dramatic floods might be the most obvious example of climate change, its effects are visible far beyond the weather. The Syrian civil war and its ripple effects have reshaped the world this year. The refugee crisis that the violence spawned, and the right-wing backlash to that crisis in both Europe and America, has been one of the overarching themes of 2016. But that, too, can be traced back to climate change; many experts point to the historic drought that gripped Syria during the 2000s as a key factor contributing to the country’s implosion. National security professionals refer to climate change as a “threat multiplier” — it may not directly trigger new threats, but it makes existing threats more dangerous, encouraging smoldering situations to erupt.

The breadth of the climate effects we’re already seeing underscores what’s at stake with the Paris agreement — and with the US election. “In the current presidential contest, we could not have a more stark choice before us, between a candidate who rejects the overwhelming evidence that climate change is happening and a candidate who embraces the role of a price on carbon and incentives for renewable energy,” climate scientist Michael Mann writes in a recent book co-authored with Washington Post editorial cartoonist Tom Toles. “If you care about the planet, the choice would seem clear.”

Americans are famous for deciding how to vote based on so-called “pocketbook” issues, like the economy. Yet for all the political polarization climate change inspires in political circles, a consensus may be building among ordinary voters: According to Gallup, the number of Americans who describe themselves as concerned about climate change has been increasing steadily for the last eight years. Perhaps 2016 will be the election year when Americans take that concern with them into the voting booth.