In 2002, with state budget deficits skyrocketing, cuts in many vital government programs – including healthcare, education, childcare and transportation – were on their way. This episode of NOW with Bill Moyers headed to California to see what may be ahead for other states. Bill interviewed Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform and architect of the conservative revolution that currently controlled the government.

Author, historian and teacher Howard Zinn lived a politically engaged life after returning from the Air Force after World War II. He talked to Bill about his opposition to a war in Iraq and the arguments he makes in his most recent book TERRORISM AND WAR.

Then, NOW went to Lincoln, Nebraska, to track down a man named Milo Mumgaard, founder and director of Nebraska Appleseed, a non-profit law center committed to defending the rights of Nebraska’s poor.

TRANSCRIPT

MOYERS: Welcome to NOW.

As I watched the news the other night, and saw the faces of young soldiers headed toward the Middle East, and then the president’s speech from Chicago on stimulating the economy by cutting taxes, I was struck by the contrast. Young Americans asking not what their country can do for them but what they can do for their country, no matter the personal cost. And the government, offering to put more money in the pockets of investors.

At the same time, a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies predicts that any war against Iraq would knock down stock prices by as much as 25%, costing the federal and state governments more tax revenue even as they are slipping and sliding into a raging river of red ink.

So Washington prepares for war, as state and city officials scratch their heads about how to provide the most basic services to people facing hard times. That’s our focus tonight, with California front and center.

Our report was prepared by NOW’s Peter Meryash and NPR’s Deborah Amos.

DEBORAH AMOS, CORRESPONDENT: Gray Davis is worried. He should be. The governor of the biggest state in the union has one of the biggest headaches in America. It hung like a bad odor over his inaugural speech on Monday:

GOV. GRAY DAVIS [at inauguration]: We face a severe budget shortfall. Its sheer magnitude boggles the mind and threatens the unprecedented progress we’ve made together. This is a national crisis, afflicting nearly every state in America.

AMOS: But no state’s pain is as bad as California’s. The deficit here could be as high as $34.8 billion over the next 18 months.

DAN WALTERS, POLITICAL COLUMNIST, SACRAMENTO BEE: Even if the governor is kiting the numbers a little bit, which he may be, it’s still the most serious budget deficit ever to hit California and probably the most serious one in relative terms to hit any state in the history of the United States.

AMOS: But California and Gray Davis are not the only ones to worry. At least 39 states are in the red, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities with estimated total deficits skyrocketing to between 60 and 85 billion dollars. Some of the worst cases:

New York – a projected deficit as high as $10 billion.

Texas – as high as $8 billion.

Illinois – as high $2.8 billion.

And in Alaska, like many other smaller budget states, a deficit as high as $896 million – more than a third of its total budget.

None of these states will get much help from President Bush’s new economic plan. He proposes sending some federal money to help tackle unemployment, but it’s only a finger in the dike. And as the President pushes for more federal tax cuts, many believe these growing deficits leave states little choice but to approve tax hikes.

That has Eunice and Bob McTyre worried. They live in the San Fernando Valley on a fixed income from Social Security, and Eunice says they can’t afford more taxes.

MCTYRE: They’re starting at the wrong point. They start talking about taxes before they make the changes or cuts that they should do.

AMOS: And there will be cuts, many of them substantial.

In health care, education, child care, transportation, law enforcement just to name a few.

There’s a legal urgency to deal with this crisis. Every state except Vermont has some kind of requirement for a balanced budget. So why are states in the red?

The weak economy has cost them tax revenues, and with less revenue they can’t pay for all the programs and tax cuts enacted when times were good and the surpluses rolled in. That’s what happened with Governor Davis and the California legislature.

WALTERS: There was irresponsibility on all parts, Republicans, Democrats, for the collective political body.

AMOS: Dan Walters is a political columnist for the Sacramento Bee.

WALTERS: They had all this money in the till. And they decided they had to empty the till. And they emptied the till on things that various political and interest groups wanted. The health care people wanted more money in health care. The education people wanted more money in education. The Republicans wanted tax cuts.

AMOS: So California’s spending ballooned. In the last 10 years, the state’s budget has grown from less than $52 billion to more than $96 billion.

And then came the bust of the high-tech bubble-tax revenues from capital gains and stock options have plummeted from $17.6 billion in 2000 to just more than $7 billion last year…a loss of revenue that accounts for 40 to 75 percent of the year’s deficit.

JEAN ROSS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, CALIFORNIA BUDGET PROJECT: California faces a very substantial challenge over the next several months.

AMOS: Jean Ross is the Executive Director of the California Budget Project, a non-profit that advocates for the poor.

ROSS: You could close down the entire state prison system, close down the state’s university system, lay off every single state employee. And you still wouldn’t close the budget gap. There will be tough choices made.

AMOS: Tough choices, in part because of California’s unique tax structure. In 1978, voters passed Proposition 13, which capped property taxes and left state officials to turn more and more to taxes on income and capital gains. That means California is heavily dependent on the fortunes of the stock market. So when the recent earthquake struck Wall Street, California’s tax revenues tumbled.

Add to this the growing burden from federal programs like Medicaid, enacted by Washington but paid for, more and more, by the states.

California’s Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal, is the medical safety-net for almost 6 million people.

Governor Davis says the program must be cut. If that happens, hundreds of thousands of the state’s must vulnerable population will lose health insurance.

Sharon Steele could be one of them.

SHARON STEELE: I try not to think of it. It’s just very frightening and depressing.

AMOS: Steele works as the choir director at her Los Angeles-area church and earns $800 a month.

She gets state money to help pay for the many medical supplies she needs, including the syringes for insulin injections and because she lost her bladder from cancer, catheters, which she needs to use 3 times a day.

STEELE: I can’t afford to buy them. If I don’t qualify for Medi-Cal I have no idea what I’m going to do.

AMOS: She says if the governor’s proposal to cut coverage for medical supplies is enacted, she would have to pay about $400 a month out of her own pocket – half of her income.

STEELE: I would have to make a choice between catheters, food, paying my phone bill, my light bill, just the bare necessities.

AMOS: As people are thrown off Medi-Cal and lose their health coverage, they often turn to places like the Venice Family Clinic, the largest free community clinic in the country. It provides a full-range of medical care to about 300 people a day.

Susan Fleischman is the clinic’s medical director.

DR. SUSAN FLEISCHMAN, MEDICAL DIRECTOR, VENICE FAMILY CLINIC: I tend to rely on our charitable network. So when I really need something for someone, I get on the phone and I basically beg favors. And I do that one by one, for each patient at a time. What does this person need and who can I call to get it for them for free? But that’s not a way to deliver health care.

AMOS: In Los Angeles county, at least 2 million people are uninsured and already 16 community clinics were forced to close down last year because of budget cuts. With more and more of the uninsured showing up for treatment, these clinics are being squeezed.

ELIZABETH BENSON FORER, CEO, VENICE FAMILY CLINIC: One of our clinics um, that I know that’s downtown is turning away fifty people a day and often has huge waits because they’re just trying to squeeze in anybody they can.

AMOS: New patients can sometimes wait weeks before seeing a doctor.

FORER: If people don’t come in and get ongoing help, they will end up in emergency rooms and sometimes they will die.

DR. ROBERT S. HOCKBERGER, CHAIR, DEPARTMENT OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE, HARBOR-UCLA MEDICAL CENTER HOCKBERGER: Our patients come here because there is no other option.

AMOS: The Harbor – UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles gets about 75 thousand emergency room visits a year, mostly the uninsured, working poor.

HOCKBERGER: I get very frustrated when I read in the papers about the inappropriate use of emergency departments for care. Um, I think a much more appropriate term would be the unfortunately necessary use of emergency departments for care because there are no options.

AMOS: The hospital itself almost fell victim to budget cuts, remaining open in large part because LA county voters passed a property tax increase to fund emergency services and bio-terrorism preparedness.

FLEISCHMAN: It’s real lives, it’s real families, it’s real people. And as you sit down with each one, and you see what they need, these are needs that don’t go away just because suddenly we don’t have the money to pay for them. And I wonder what will become of people.

AMOS: Everything is on the chopping block. The governor has already proposed cutting the $41 billion education budget for Kindergarten through 12th grade as well as the state’s universities and colleges.

ROSS: I think most Californians understand that there needs to be a balanced approach. They want government to do the best it can with every tax dollar. They want government to tighten its belt wherever they can. But I think taxpayers also understand that they want quality public schools. They want health care. They want environmental protection. And they understand that that will take a balanced approach of some spending cuts but also some revenue increases.

AMOS: Revenue increases? Taxes. And that’s what troubles Eunice McTyre, who lives on $1,800 a month from Social Security.

MCTYRE: And if they suddenly keep raising our taxes, what else is that going to take away? I mean, the only thing we have left is, we have to sell our house. And then where do we go?

AMOS: McTyre wants the state first to cut what she says is government waste and overly generous state pensions and salaries.

MCTYRE: They look at it the wrong way. They have to change things. Not just come along and ask for more money.

AMOS: And that’s the heart of the problem. Powerful Democrats who control the state assembly don’t want to cut programs that will hurt the needy, and although Republicans are in the minority, they hold veto power and oppose new taxes. A two-thirds majority is needed in California’s legislature to pass a budget or to raise most taxes, so Davis will need some Republicans to sign on to any solution.

WALTERS: You’re asking a bunch of very short terms politicians with their eye on the next election to make some– rational long term decisions that may not have any immediate political payoff. And that’s the essence of what got ’em into the problem and that’s the essence of the difficulty they have to face to get– out of the problem.

AMOS: All that red ink is not a pretty picture. The states have long been called the laboratories of democracy. But as they struggle now with how to balance spending cuts and new taxes to deal with those deficits, they are putting democracy to the test. The choices will be painful.

BILL MOYERS: If states refuse to raise taxes to fix some of those problems we’ve just seen, that certainly won’t bother my next guest. He’s a sworn opponent of all taxes. He’s also the most powerful man in Washington not to hold a public office.

Officially, Grover Norquist heads an organization called Americans for Tax Reform where for almost 20 years now he has crusaded for lower taxes and less government. Unofficially he’s been the linchpin in Washington for the conservative revolution that now controls the government. His weekly meetings of activists became the politburo of strategy where all stripes of conservatives bear their differences in order to bury their hatchet in Democrats. From the Christian coalition to log cabin Republicans to the National Rifle Association on whose board he sits, this Harvard graduate keeps the troops on mission and on message. His success prompted Senator Hillary Clinton to muse aloud, if only Democrats had a Grover Norquist. Welcome to NOW.

GROVER NORQUIST: Glad to be with you.

BILL MOYERS: Well, you do have it all. You have the White House, the Congress, the regulatory agencies, the courts more or less. The last time Democrats, liberal Democrats, held that kind of power, they made some mistakes like the war in Vietnam that they couldn’t sustain the support of at home, emphasized parochial interests at the expense of the sort of bedrock universal values of American society. What are the errors you think conservatives running everything could make?

GROVER NORQUIST: I think it’s very important to always make sure that you’re talking to the entire coalition and to as many Americans as possible; not to go chasing after one little group or another. The Democrats would bring new groups into their party and not notice that larger groups are going out the back door. And so what I try and do whenever I work on an issue or work with political leaders is make sure that when you’re talking about a new approach, how does that…how does the entire coalition view that new approach? Is there a better or different way to do it that irritates fewer people and that satisfies a larger constituency?

BILL MOYERS: And that’s what you did at your Wednesday morning meetings? Those meetings became famous, for all kinds of conservatives being in there hammering things out.

GROVER NORQUIST: And we now have 27 versions of that at the state capital level, including one in New York City. So we’re taking the model of the “leave us alone” coalition from the national level to the state level as well.

BILL MOYERS: “Leave us alone?”

GROVER NORQUIST: Um-hmm. Look, the center right coalition in American politics today is best understood as a coalition of groups and individuals that on the issue that brings them to politics what they want from the government is to be left alone. Taxpayers, don’t raise my taxes. Property owners, don’t restrict or limit my property. Home schoolers, let me educate my own kids. Gun owners, don’t restrict my Second Amendment rights. All communities of faith, Evangelical Christians, conservative Catholics, Mormons, Muslims, Orthodox Jews, people want to practice their own religion and be left alone to raise their own kids.

BILL MOYERS: Do you have any sympathy for those states we just saw a few moments ago? Under the president’s plan, those states do not expect any direct aid from Uncle Sam. Do you have any advice for them?

GROVER NORQUIST: Sure, two things. The most important thing for President Bush and the federal government to do is to create a pro-growth economic policy because its economic growth that brings in more revenue for states and local governments. At the state level what they really have to do is take a long run view and limit the growth of spending, put limits on how much you spend. And then California, the state owns a whole bunch of land and other things that it could sell off it doesn’t need, and it needs to figure out which of those government jobs need to be in government, and what can be privatized or contracted out.

BILL MOYERS: What the states are saying, though, is that since they get no direct aid, the conservative philosophy in government is actually pushing them over the cliff now.

GROVER NORQUIST: No, I would argue if you look at those states that have conservative governments, and there are only a few: Colorado, Florida –you’re looking at states that are in fairly good shape. We have Reagan-ized the Republican party at the national level over the last 20 years. It has not happened at the state level. What happened at the national level was pre-Reagan we couldn’t go to a Republican politician and say, you should be more…they say I should be more what? I’m better than the Democrat I beat, what do you want from me? You should be more like Goldwater, he lost. After Reagan he was the model for House and Senate people, and today 95 percent of House Republicans and 80 percent of Senate Republicans are Reagan Republicans. That does not yet exist at the state level.

BILL MOYERS: But George W. Bush has become like Reagan, too.

GROVER NORQUIST: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: Huge tax cuts, huge increases in military spending, and huge deficits. I mean, it does seem to a lot of us that conservatives have become fiscally irresponsible.

GROVER NORQUIST: Well, two things. One was September 11th, the slowdown in economic growth, we went from surpluses into deficit. Spending has been going too rapidly both before President Bush and including into this administration. That’s why if you look at his budget there are two sides to it this year. One is the significant tax reduction ending the double taxation of dividend income. The other part that he has talked about and that we’re going to be fighting about all year, is spending restraint.

BILL MOYERS: But the spending restraints on defense? There are none there.

GROVER NORQUIST: Well, you had asked, are there some problems conservatives can have? Can we make mistakes? Let me suggest two things we need to be very careful of. We cannot allow anything that’s called national defense to justify any and all spending. We need to be very, very careful that we don’t overspend and say, oh, that’s defense, when perhaps it isn’t.

BILL MOYERS: Here’s the question. In a time of war and fiscal woe, why not ask rich people-a little sacrifice of rich people?

GROVER NORQUIST: Well, I think what we’re looking to do is to create a pro-growth economic policy that will create opportunities for all Americans. The job of the government isn’t to go around and try and make people sacrifice, it’s to try and make people free. The reason why we have a national defense is to protect our freedoms.

BILL MOYERS: But what about those real people we saw in that film, the woman who needed the health insurance, who needed the health coverage, who was going to have to take $400 out of her $800 a month salary to meet medical costs that she didn’t have?

GROVER NORQUIST: I think you have to look at the total level of what government does to her in terms of the taxes that they impose on…

BILL MOYERS: She’s not paying much taxes, though, at $800 a month.

GROVER NORQUIST: And she’s got…well, she’s paying sales tax in that state, she’s paying Social Security taxes in that state.

BILL MOYERS: But aren’t all of those taxes sort of the membership dues we pay for living in a cooperative and collaborative society?

GROVER NORQUIST: Well, first we have to decide what we want the government to do. What is it legitimate to require with force people to pay for? It is not charity. I mean, guys with guns will show up if you don’t pay your taxes and take that money from you. And I think that we want in order to have a free society to have as little as possible done coercively.

BILL MOYERS: Here’s The Washington Post, December 16th. “As the Bush administration draws up plans to simply the tax system it is also refining arguments for why it may be necessary to shift more of the tax load on to lower income workers.”

GROVER NORQUIST: Well, I haven’t seen that argument, but I think the tax load is so heavy that we can reduce it, we don’t need to be shifting it, adding it to anywhere else. The President is not talking about increasing anyone’s taxes, his proposal is simply one of reducing taxes.

BILL MOYERS: Let me tell you what I think the mistake the conservatives could make, because I saw the Democrats make it. So many Democrats came to Washington as outsiders and stayed to become consummate insiders. And I saw it with Clark Clifford, I saw it with Bob Strauss, I saw it with Vernon Jordan. And all of those people who came to Washington to do good and stayed to do well, they have become the political, lawyerly and lobbyist aristocracy of American life. And I see Republicans doing that, too. I mean, I don’t see Dick Armey going home to teach at West Texas State University, he’s joining a Washington lawyer lobbying firm. I mean, you all are making the same mistake that the Democrats made, which means both parties are going to wind up serving the American aristocracy.

GROVER NORQUIST: Well, I think we need to be very, very careful about that. I know the activists I deal with, we sort of try and check each other to make sure that we haven’t gone native, that you come to Washington thinking it’s a cesspool, you don’t want to end up thinking it’s really a hot tub and getting used to it. So that’s something one has to keep an eye on all the time.

BILL MOYERS: Is the conservative movement is going to be seen as the servant of the aristocracy?

GROVER NORQUIST: I think that the left has always made that accusation and I think that liberal Republicanism of the 1950s suffered from that. The great thing about President Reagan is that he changed the nature of the Republican party, is a party dedicated to limited government. It is not the pro-business party; it is the pro-freedom party. And for competent businesses, that’s all they ask for. Incompetent businesses that want subsidies, they’re not our friends, they’re our opponents.

BILL MOYERS: What would you do about real life situations like this? This is a story out of New Jersey, the caseworker who closed a child abuse investigation and to a mother whose son was found dead in a locked basement here on Sunday had been working on more than 100 other investigations at the same time. That’s more than six times the national standard recommended by national child advocacy groups. The New Jersey Division of Youth and Family Services says its field agents juggle an average of 35 cases. Why shouldn’t those of us who are well off be taxed a little more to try to make a system like this work for those who have nothing at all?

GROVER NORQUIST: Because I’m not interested in saving that system. I’m interested in saving and protecting the kids that that system is supposed to help.

BILL MOYERS: How would you do it?

GROVER NORQUIST: Well, I’ve been active with groups, the Institute for Children and some of the pro-adoption groups in Washington, D.C. The last numbers I saw, there are about 500,000 kids in foster care, about 50,000 kids free to adopt, and more than a million parents looking to adopt. And we have state rules and federal rules that are being liberalized, but that up until this point have made it difficult for kids to get adopted. And, the rules are…the Federal government gives subsidies to state governments, institutions like that, for every kid they keep in foster care, and they lose the subsidy if they get the kid adopted. That is the wrong kind of incentive to have. Nobody should have 100 kids they’re chasing after…

BILL MOYERS: This is the real world, this is the only system these people have.

GROVER NORQUIST: We need to get them out of that system and into families where they’re adopted. There are more people who want to adopt than there are kids that need to be adopted. And the government is in the way of having that happen.

BILL MOYERS: But in the meantime, can we hire more caseworkers, more people, to look after these children?

GROVER NORQUIST: As we’re finding out, the government isn’t looking after those children, and no government can look after children the way a family could, the way parents could. Let’s get those kids into real families and adopted by real families who will take care of them.

BILL MOYERS: You’re on record as saying, my goal is to cut government in half in 25 years, to get it down to the size where we can drown it in the bath tub. Is that a true statement?

GROVER NORQUIST: No. The first part is an accurate statement of exactly what we’re trying to do. We’ve set as a conservative movement a goal of reducing the size and cost of government in half in 25 years, which is taking it from a third of the economy down to about 17 percent, taking 20 million government employees and looking to privatize and get other opportunities so that you don’t have all of the jobs that are presently done by government done by government employees. We need a Federal government that does what the government needs to do, and stops doing what the government ought not to be doing.

BILL MOYERS: Given all this, are you for the war against Iraq?

GROVER NORQUIST: I think given what’s been going on in that neighborhood we are going to go in and remove Saddam Hussein and hopefully establish a free society in Iraq.

BILL MOYERS: When do you think that will happen?

GROVER NORQUIST: [LAUGHTER]

BILL MOYERS: Next two weeks?

GROVER NORQUIST: Next two months.

BILL MOYERS: Next two months. After the State of the Union message?

GROVER NORQUIST: Oh, I hope we aren’t quite calculating it that much, but I do think…

Yes, yes. Sometime…February? I’m guessing. Nobody’s told me the date here.

BILL MOYERS: You know what I’d like to ask you to come back from time to time and let’s keep this discussion going and see what happens to the conservative movement.

GROVER NORQUIST: Okay. Well, we work at it every day, and we try and keep honest and we try and keep on line and we try not to get distracted by Washington.

BILL MOYERS: You were quoted yesterday of saying now that conservatives are in power it’s the gentrification of Washington.

GROVER NORQUIST: I was teasing, but I was talking about the number of Republicans who are coming into Washington, which is helpful. But we’re really winning when Republicans start leaving Washington because it becomes less important.

BILL MOYERS: Thank you very much, Grover Norquist.

GROVER NORQUIST: Thank you.

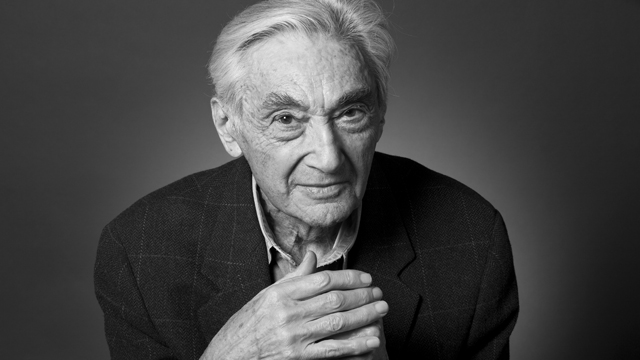

HOWARD ZINN

BILL MOYERS: We’ve been talking to people on this program who take different positions about the impending war with Iraq. Tonight’s guest is opposed and argues his case in this new book, TERRORISM AND WAR.

The author is the historian and teacher Howard Zinn, who has lived a politically engaged life since he came home from the Air Force after World War II.

He grew up on the tough streets of Brooklyn where he worked as a teenager in the shipyards, earned his doctorate in history from Columbia university, and while teaching college became an activist in the civil rights movement and the opposition to the Vietnam War.

Among his many books is this one – A PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES, written from the point of view of men and women left out of the official records of the American epic. Since its publication in 1980 it’s become a touchstone of dissident thought in America.

Howard Zinn was in town the other day, and I talked to him about the United States, terrorism, and Iraq.

BILL MOYERS: As of now, do you think war with Iraq is imminent?

HOWARD ZINN: It feels imminent. It feels immanent simply because the Bush administration seems absolutely determined to have a war no matter what– no matter what the opposition is, no matter what the international community thinks. No matter how reluctant people in this country are. And I do believe there’s a lot of reluctance in this country about war.

BILL MOYERS: What are the real reasons, in your opinion, for why we’re going to war? I mean we know the stated reasons, weapons of mass destruction, all of that. Why do you think they are so eager to go to war?

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah, I mean there’s no doubt– as you say there are stated reasons. None of those stated reasons make sense, you know? Saddam Hussein is a tyrant– well– we’ve tolerated tyrants– lots of them. We’ve put tyrants in power. You know, weapons of mass destruction, well we just had an example. Korea has more weapons of mass destruction than Saddam Hussein but we’re not making war on Korea. So, if– I think oil is one of the important factors. But I think that there are others. And one of them has to do with something psychological. That macho feeling that people in power have about the United States being the number one superpower and determined to show it.

BILL MOYERS: Is there any evidence they could present or any argument they could make that would give you second thoughts about your opposition to the war?

HOWARD ZINN: (LAUGHS) I can’t think of any. And I think there’s a fundamental reason why I can’t think of any. If we go to war, we will kill thousands, tens of thousands, we don’t know how many people. A hundred thousand? We will kill huge numbers of people. And who will we kill? We will kill the victims of Saddam Hussein. If we go to war against Iraq, we are killing the victims of the tyrant. That to me creates a moral equation which is intolerable.

BILL MOYERS: A moral equation?

HOWARD ZINN: I mean– I mean that one of the moral principals about war and about just war you know, is the issue of proportionality. And that is what harm do you do in the course of a war– in the furtherance of some end. Even presuming the end is good. The end, however moral it appears to be, is always uncertain. So, when you’re faced with a certain terrible means, and uncertain end, to me it is very clear you mustn’t go to war.

BILL MOYERS: This is the kind of war that the terrorists are fighting right now. I mean when they drove those airplane bombs into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, they were striking innocent people for their own purposes.

HOWARD ZINN: Exactly. Exactly.

BILL MOYERS: Are you saying that’s what we’re about to do in Iraq?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, that’s right. I mean– there’s– it’s a– war is a form of terrorism. I know there are people who don’t like to equate– what was done– you know on September 11th, 2001, they don’t like to equate that with a war that the United States engaged in. Sure, they’re different. But they’re not different in the– in the fundamental principal that drives the terrorists and that is, they’re saying, we’re going to kill a lot of people but it will be worth it. We’re trying to do something. We’re trying to accomplish something. They– the terrorists are not killing people just for the sake of killing people, they have some end in mind. To show that the American empire is vulnerable or to make some point about American policy in the Middle East. But they have an end in mind. We are doing the same thing. I mean, as I say, the details are different, but we are willing to kill a lot of people for some political end that we have declared.

BILL MOYERS: And in this case, it’s ridding the world of a regime that President Bush says is part of the Axis of Evil.

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah, well, you know– (LAUGHS) there are so many evil countries in the world. So, I don’t really believe him when he says we simply want to rid the world of an axis of evil. And also, there’s something else. There are too many places in the world that require attention because human beings are suffering. If we care about human beings, and presumably the reason we are going to depose Saddam Hussein is, oh, we care about the human beings in Iraq whom he has tyrannized. And of course, we should care about them. But, we have– drawn a line around this little country in the Middle East and said, “This is where all evil reposes.” And we are shunning our eyes to the deaths of millions and millions of people. Which is not a potential, which is not a potential like Iraq having a nuclear weapon. But which is a present, ongoing reality. And what is the United States doing about AIDS in Africa? It is giving a pittance to help the people in Africa while it is concentrating on this war in Iraq.

BILL MOYERS: If you were convinced that Saddam Hussein has or is about to get nuclear weapons, would you change your mind?

HOWARD ZINN: I wouldn’t change my mind about waging war. No. I’m not surprised at the thought that Saddam Hussein may be concealing his weaponry and so on. What is– ironic to me is that– we think that Saddam Hussein, who may possibly have a nuclear weapon, is such a threat as to require an immediate war. When– and here, what I’m going to say really comes from the CIA. And I don’t usually say things that come from the CIA.

BILL MOYERS: I don’t see you hanging around the cafeteria at the CIA.

HOWARD ZINN: No, no, they don’t confide in me, you see. But the– the CIA has said that the most likely use of weapons of mass destruction by Iraq would come if we waged war. And of course that makes sense. He is totally surrounded by enemies. He’s totally overwhelmed by American military power. The one time he is likely to use his weapons is if he is attacked and he is desperate. Now, that makes common sense.

BILL MOYERS: What would be your alternative to war? What would you do about– a despot like that who has brutalized his own people.

HOWARD ZINN: Yes. Yes.

BILL MOYERS: Invaded his neighbors. Threatened Israel. What would you do about it?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, the United Nations, I think, had it right when the United Nations charter was adopted right after World War Two. And according to the United Nations charter– countries may not make war on other countries preventatively. You can make war on other countries, you know, if other countries are an immediate, immanent threat. If they are doing something.

BILL MOYERS: You could say that the terrorists declared war on the United States in 1979 when the Iranian extremists seized the American embassy and held hostages for over a year. Then, there was the attack on the Marine barracks in Lebanon that killed over– almost 300 American Marines. There were the bombings of the American embassy in Nairobi and Tanzania. There were Saddam Hussein’s effort to kill former President Bush in 1994 when he went to Kuwait. You could say that the terrorists have been carrying on a war against the United States for a long time now. And that they have been encouraged by our ineffectual responses to them, to believe that we’re paper tigers. And that George W. Bush is at least saying to them, “We’re no longer a paper tiger.”

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah. Well, you know, we didn’t always respond ineffectually. And we didn’t always respond– (LAUGHS) non-violently. President Clinton responded to the bombings of the embassies with bombings. With– you know, bombing the Sudan. Right? Bombing Afghanistan. He responded with bombings and-

BILL MOYERS: And hitting a pharmaceutical company instead of a terrorist nest.

HOWARD ZINN: Exactly. And the point is that– are terrorists going to be deterred– are terrorists going to be scared if we react violently? No. They love it. That’s what they dote on. They dote on violence. They dote on having more reasons to commit more terrorism. We solved the problem of the hostages in Iran by negotiations. You know? And– there are many situations where we engage in violence and in wars that could be solved by negotiations. There were people who said, you know, Curtis LaMay, Joint Chiefs of Staff. Let’s nuke the Soviet Union before they do it to us. You know? Well, it would have been a horrible scenario. It would have been tens of millions or 100 million people dead–

BILL MOYERS: So you’re saying that we could-

HOWARD ZINN: We waited– And under the surface of that tyranny, people developed an opposition to the regime, and the moment came when things changed.

BILL MOYERS: Do you take terrorism seriously? The threat of terrorism seriously?

HOWARD ZINN: I do take the threat of terrorism seriously. You cannot eliminate that threat or diminish that threat by bombing a country. By singling out Afghanistan and killing large numbers of people. That doesn’t do anything with terrorism.

BILL MOYERS: But Afghanistan is no longer a nest for terrorism?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, I’m not sure of that. You don’t know who and where there’s a nest of terrorism. The thing about nests for terrorism is they’re not easily located.

BILL MOYERS: But with all due respect-

HOWARD ZINN: Yes?

BILL MOYERS: If you were George W. Bush, you would– think after 9/11 that attacking the place from which the terrorists may well have come was self-defense.

HOWARD ZINN: Oh, I think he can persuade himself– you know, I think the people in Washington-

BILL MOYERS: We were attacked. So, the President– you know, you’re a student of the Constitution-it talks about the common defense there.

HOWARD ZINN: Oh, sure. The– we were attacked, but then the question is, who attacked us? If we could locate the people who attacked us and get them, grab them, find them. Okay, that’s self-defense. But if we are attacked and we don’t know who attacked us, and we just select a country from which we think the attackers may have sprung, and then just bomb that country, that is not defense. That is indiscriminate violence.

BILL MOYERS: But there was no doubt about where Bin Laden was.

HOWARD ZINN: Yes, but it’s like– you know, there’s no doubt that this murderer is hiding out in South Boston. So, let’s bomb South Boston. You know? Because he probably has even friends in South Boston who are hiding him out. Let’s bomb South Boston. We may kill 1000 people in South Boston, and by the way, we may not find the murderer. Will we call that defense? No. I don’t think so.

BILL MOYERS: Did you think when you were dropping bombs in Europe that you were defending the United States?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, actually-

BILL MOYERS: Or civilization?

HOWARD ZINN: Civilization. I probably did. I probably did. But that was a case of real defense.

BILL MOYERS: You dropped lethal weapons on military and civilian targets below you. What was going through your mind when you do something like that?

HOWARD ZINN: Remember this. When you’re bombing, you bomb from 30,000 feet. And six miles up, you don’t see any people. You don’t hear screams. You don’t see blood. You don’t– you know– see limbs being torn from people. You just see a target. And you’re aiming for that target and you’ve done this again and again. You’ve dropped bombs on targets where you never saw human beings– this is the nature of modern warfare. And this is why huge numbers of people can be killed– and– they don’t register as human beings to you. Kill at a distance. I’m sure the men who dropped the bombs on Hiroshima did not see what was going on down below. They were just bombing a target. So, yes, I looked through the bombsight and I was just aiming for this target which had been identified for me by the intelligence people before we went off.

BILL MOYERS: Tell me what happened over Royan?

HOWARD ZINN: Oh. That’s this little town on the Atlantic coast of France. And that experience, I think, has something to do with that attitude towards war, even so-called good wars that I developed after World War Two. A little town on the Atlantic coast of France and we thought, I– with my bomb group in East Anglia in England thought we were not going to fly any missions anymore. The war was about to be over. It was a few weeks from the end. Everybody knew that. And then suddenly we were aroused in the middle of the night, told we’re going to bomb this little town. Why? Well, they said there’s several thousand German soldiers there. They’re not doing anything. Talk about pre-emptive.

BILL MOYERS: They’d been left behind– by this time the Allies had rolled across France.

HOWARD ZINN: Absolutely.

BILL MOYERS: And these had been left behind in a pocket.

HOWARD ZINN: Exactly. The Allies roll across France into– into Germany. We’re surprised that here were these German soldiers. They’re just waiting there on the edge of the sea, waiting for the war to end and we are going to bomb them. And so we sent– and I didn’t know the number of bombers. It’s interesting, when you’re in a military operation, you don’t see the larger picture. I knew our 12 bombers from our base were going over. I didn’t know that 1200 bombers were going over this tiny town.

BILL MOYERS: 1200?

HOWARD ZINN: 1200 bombers. Yes, 1200 heavy bombers, 1200 B-17s went over this town of several thousand French people with the several thousand German soldiers around it. And we dropped what they called a– it was what they told us in the briefing room, you’re going to drop jellied gasoline instead of your usual demolition bombs. Napalm. It was the first use of napalm in the European theater. And– we did this. I– I didn’t even think about it twice. I mean to this day, I know– I can understand how atrocities are done by ordinary people. You know. What Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil.” I understand how– because I– I didn’t even think about it. I was just trained to drop bombs. There is the enemy, you make a decision at the beginning of the war, they’re the bad guys, you’re the good guys, and therefore everything goes. And so we just did this. And so, we destroyed the town of Royan. Killed Frenchmen, killed women, children, killed the German soldiers. Victory. And it was only afterwards– it was only after Hiroshima and Nagasaki that I thought about that. And then I thought about Dresden. And then I thought about the other– killing civilians in the war. Unnecessary even from the point of view of winning the war. And I thought war brutalizes everybody involved in it.

BILL MOYERS: Is your conclusion that we should not fight wars then because there will be civilian casualties?

HOWARD ZINN: Yes. (LAUGHS) Yes.

BILL MOYERS: Does this make you a pacifist?

HOWARD ZINN: No. I– I– I avoid the word pacifists. And the reason I avoid it– is that it suggests passivity. That is people think of pacifists as somebody who are going to sit by and do nothing while, you know, maybe mediate, while terrible things go on in the world. No. I mean– I think– I keep coming back to the fact that political tyrannies like Iraq have to be juxtaposed against other problems in the world which are very, very serious. I don’t believe in passivity. I believe we should do something about these problems. But we should not do war. Because war makes things worse than they were before. War has consequences which you cannot predict.

BILL MOYERS: How would you have us fight terrorism?

HOWARD ZINN: What I’m suggesting is change our posture from that, from a military superpower to a humanitarian superpower. We are enormously wealthy. Let’s use that wealth to send medicine to Africa. Let’s use that wealth to help change social and economic conditions around the world.

BILL MOYERS: So, here we are a few days away from that decision and possible war. What do you think is going to happen?

HOWARD ZINN: I don’t know. I’m a historian. Historians don’t know what’s going to happen. They guess like everybody else. I think– we’ll probably go to war. I’m not sure. I hold out– always hold out a hope that– the President will look around and think there’s not enough enthusiasm in the country for the war. And maybe when they see the casualties, even a small number of casualties– maybe my– and then this is the way he’ll think about it. Maybe my political fortunes will decline instead of rise. Maybe I’ll be blamed instead of praised. I’d like to think that that’s a possibility. But I think it’s only a possibility. But you act on the basis– not of probabilities, but of possibilities. If you act against war, even if you think that probably we’ll go to war, because you know that in the past, there have been times when something only seemed possible and yet it came to pass.

MOYERS: It is a long way from the Persian Gulf to Lincoln, Nebraska, a long way as well from the clash over budgets and taxes in Washington. But Lincoln, Nebraska, is a good place to go to be reminded that when matters are out of our hands, it still matters what we do with our hands.

My colleague Keith Brown went to Lincoln to track down a man named Milo Mumgaard whose family arrived on the Great Plains generations ago, and who now stretches out his own hand, to offer hospitality to strangers.

KEITH BROWN: America’s heartland — it’s been a destination for generations of Eastern European and Scandinavian immigrants in search of opportunity. Nowadays there’s a new wave — tens of thousands of immigrants from Mexico and Central America bypassing Texas, Arizona and California, to make the wide-open spaces of the midwest their new home.

In Nebraska, they’ve found an advocate in Milo Mumgaard. He’s a native Nebraskan, a devoted family man, and a New York University trained attorney with a passion for justice.

MILO MUMGAARD: Our system of government and law and justice have generally not been fair in so many critical ways to working people — to minorities — to those who do not have the means or the skills to really use the system.

KEITH BROWN: Mumgaard is the founder and director of Nebraska Appleseed, a non profit law center committed to defending the rights of Nebraska’s poor. Lately, his work has been focused on the state’s newcomers, those whose dreams have been met with unforeseen hardship.

MILO MUMGAARD: We are in a position where they are contributing to our community and our society but have to live in the shadows because of their undocumented status.

KEITH BROWN: Are they are burden on the system though?

MILO MUMGAARD: The reality is that undocumented workers are not a burden on the system. This is a population that works, that contributes to the overall economic vitality of, of the area and so on.

KEITH BROWN: Over the last 10 years, the Latino population in Nebraska has exploded to nearly one hundred thousand. Rural towns and small cities, once all white, are now thirty, forty and in some cases more than fifty percent latino. Schuyler, for example was only 4 percent latino in 1990. Now it’s up to 45 percent. And that does not include undocumented residents.

One of the lures for them is Nebraska’s huge meatpacking industry.

MILO MUMGAARD: It’s vital to the economy of my home state to have a health industry. Nebraska is the number one beef packing state in the country. If you’re eating a steak in New York, chances are it came from here.

KEITH BROWN: And chances are it passed through the hands of an immigrant from Mexico or Central America. Latinos make up 70 to 80 percent of the workers in Nebraska meatpacking. The work is dirty and hard. And, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, it’s the most dangerous occupation in America.

MILO MUMGAARD: It’s an incredibly fast work place. And it’s all driven by a chain line that the steers killed on one end and it’s boxed up at the other end. People are in a very compact environment. They have lots of knives, and just imagine the blood and the guts and the slippery nature of everything. You add all that together and you’ve got a lot of injuries.

KEITH BROWN: For every 100 workers there are 25 reported job related injuries and illnesses, many of which leave workers permanently disabled. Mumgaard calls them the walking wounded. And says even those who escape injury have a hard time getting by.

MILO MUMGAARD: We’ve been criticized, actually, Appleseed, for referring to meatpacking jobs as sub-poverty wages. And the reason we refer to it that way is-it is certainly not a wage that could support your family.

KEITH BROWN: In fact, meatpacking is one of the lowest paid industrial jobs in America. But at seven to nine dollars an hour, the wages are certainly attractive to Latino immigrants — who often earned 7 to 9 dollars a day in their native countries. Yet no matter the wages, the harsh conditions inside the slaughterhouses make the job short-lived for many. And the injured are often left out on their own.

Nebraska Appleseed joined forces with other organizations and rallied the support of lawmakers to address the needs of these workers. It resulted in a workers bill of rights that established minimum workplace guidelines that include: the right for workers to organize, to a have a safe workplace and to be able to seek state help.

MILO MUMGAARD: We are not asking for revolutionary change here. All we’re asking for is decency and fairness and humane treatment of workers.

If we can do things that actually show that things can happen – then they can have over time the effect of mobilizing, engaging, inspiring more and more people to get engaged and more and more will happen.

KEITH BROWN: Mumgaard formed Nebraska Appleseed six years ago in his basement with help from the Washington D.C.-based National Appleseed Foundation. The organization is now supported by local and national foundations, and has a staff of 14 lawyers, associates and volunteers to help carry out its mission.

These days that involves heading off new strains brought on by the state’s changing demographics. Some longtime Nebraskans question if their new neighbors are only here to feed off the land, with no interest in assimilating.

MILO MUMGAARD: There is undertow of, are people really wanting to be here? Are they really just here working taking advantage of the good life but not willing or interested in being a permanent part of Nebraska.

KEITH BROWN: Is that true? Is it warranted?

MILO MUMGAARD: And the answer to that is – and that’s not true. It’s probably a reflection of latent biases and discriminatory attitudes, sort of couched in terms of well – you know Mexicans don’t really want to be here! And that’s just not the reality.

KEITH BROWN: The reality is: new immigrants have revitalized some of Nebraska’s once dying towns and cities. Single men who first came to Nebraska are now bringing their families. They are buying homes and starting small businesses — all indicators, Mumgaard says, that they are here to stay.

MILO MUMGAARD: People want an integrated Nebraska. Everybody wants that.

KEITH BROWN: Now a significant portion of Mumgaard’s time is taken up not just with changing laws, but with changing minds. This Sunday, a talk at the First Lutheran Church in Lincoln veered to issues of integration.

MAN #1: You know when our forefathers came here from Scandinavia or Germany or whatever, when they came here, yeah, they formed their little communities but they were always taught in English. Everything was in English then. And they didn’t object saying well we want our stuff in Swedish.

PAUL: That isn’t really true. The – even the church that I went to was – they were preaching in Swedish in the church. There were after school Swedish things.

MAN #2: I know that in my folks’ community, they spoke Swedish all the way up through school and they spoke Swedish. But yet when they went to school, they had to learn things in English.

KEITH BROWN: In America’s changing heartland, where Swedish has given way to Spanish, Mumgaard has become a consistent voice for Nebraska’s poor and disenfranchised.

MILO MUMGAARD: I’m not a working poor person; I’m not a new immigrant; I’m not a welfare recipient; and I’m not and won’t ever be in their shoes, but I care! This is a function of who I am. I don’t have any psychoanalytic insight into why I give a damn as much as I do, but rather I have this conscious recognition that I give a damn!

This transcript was entered on August 20, 2015.