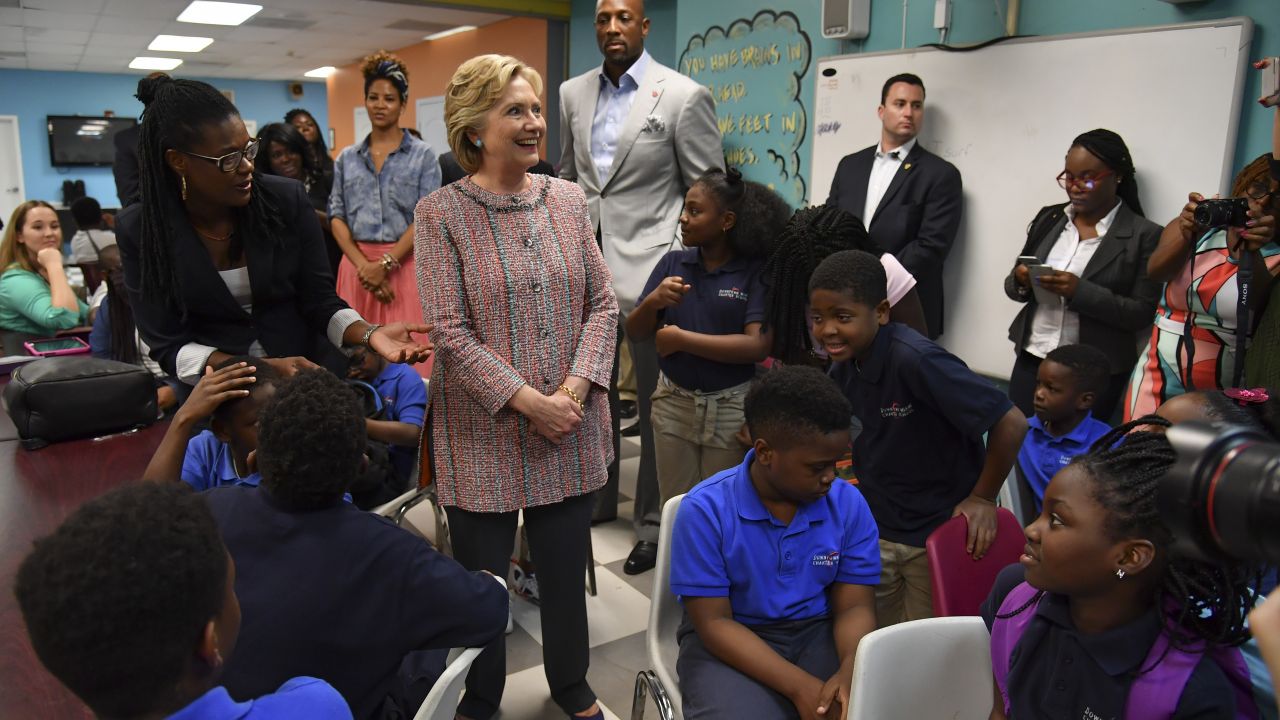

Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton greets students, joined by NBA Hall-of-Famer Alonzo Mourning and his wife, Tracy (rear center), during a visit to Overtown Youth Center on Oct. 11, 2016 in Miami, Florida. OYC is a Mourning Family Foundation project, founded in 2003 by Mourning to create a safe haven for children living in Overtown, a historically black and predominately low-income community in Miami. (Photo by Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

It would be wrong to ignore the psychological, social and political damage this poisonous election is causing. When the movement called Citizen Therapists Against Trumpism, an effort to awaken therapists to their public responsibilities, commissioned a study of 1,000 voting-age Americans, 43 percent reported emotional distress from Trump and his campaign. But 28 percent also feel distress from the Clinton campaign. As many have observed, beyond proposals for new government programs it is hard to see an inspiring vision coming from Clinton. This absence is part of a larger crisis in government-centered views of democracy. “The liberal story that has ruled our world in the past few decades … is collapsing,” writes Yuval Noah Harari in a recent New Yorker. “So far no new story has emerged to fill the vacuum.”

But in the midst of a dismal election, it is possible to see signs of a democratic awakening. This way of seeing puts citizens – not government, markets or powerful leaders – at the center of politics, problem-solving and the creation of a democratic way of life.

I learned about a citizen-centered view of democracy in the civil rights movement.

In 1964, too young to vote — change in the voting age came in 1972 — I proclaimed with the zeal of an 18-year-old to Oliver Harvey, the janitor at Duke who was organizing a union, that “there is no difference” between Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater,” the presidential candidates of the Democratic and Republican parties that year. “Johnson won’t desegregate the South!” I said.

Harvey replied, “That’s ridiculous. That’s what we’re doing, desegregating the South.” But Harvey also detailed the ways in which a president could make a difference in our work – helping shape the public narrative, supporting legislation, making federal appointments, protecting civil rights workers and more. He was making the point that while government – and politicians – are crucial partners, the driver of change and democracy itself is the people.

This was, in fact, the original view of those who invented the word democracy. As the classical scholar Josiah Ober shows in his essay, “The Original Meaning of Democracy,” democracy for the Greeks did not mean voting. It meant, “more capaciously, the empowered demos… not just a matter of control of a public realm but the collective strength and ability to act within that realm and, indeed, to reconstitute the public realm through action.”

In the early 1830s, the French observer Alexis de Tocqueville revived this view in his reflections on American society. “In democratic peoples, associations must take the place of the powerful particular persons,” he wrote in his classic, Democracy in America. The people as agents of democratic change continued over the sweep of American history. As the great sociologist Robert Bellah put it, “political parties [in America] often come in on the coattails of successful popular movements rather than leading them.” In The Story of American Freedom, Eric Foner shows this dynamic in the 1930s. “It was the Popular Front, not the mainstream Democratic Party, that forthrightly sought to popularize the idea that the country’s strength lay in diversity and tolerance, a love of equality, and a rejection of ethnic prejudice and class privilege.”

A citizen-centered view of democracy emphasizing the agency of the people was widespread in the civil rights movement. Septima Clark, an architect of the movement’s citizenship schools whom Martin Luther King called “the mother of the movement,” articulated their purpose: “To broaden the scope of democracy to include everyone and deepen the concept to include every relationship.” Vincent Harding, sometime speechwriter for King who served with my father on the executive committee of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, argued similarly. “The civil rights movement was in fact a powerful outcropping of the continuing struggle for the expansion of democracy in the United States,” he wrote. “It demonstrates…the deep yearning for a democratic experience that is far more than periodic voting.”

Here are three signs that a citizen-centered view of democracy is awakening again:

Government of the People

Democracy as a way of life that the people create is suggested by Abraham Lincoln’s view of government “of the people, by the people, for the people.” In the 20th century, this view sometimes found large-scale expression.

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union holds a meeting in East Arkansas, June 18, 1937. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Jess Gilbert in Planning Democracy: Agrarian Intellectuals and the Intended New Deal, describes a striking example. From 1938 to 1941 a group of agrarian leaders in the Department of Agriculture worked with land grant colleges, cooperative extension workers and community leaders to develop a democracy initiative on rural America. “They believed that democracy required continuous learning, personal growth, cultural adjustment and civic discussion,” writes Gilbert. The effort involved farm organizations and unions, churches, youth clubs, professional and business groups, and government agencies, training about 60,000 discussion leaders. In all, the project involved 3 million people. It conveyed the idea that democracy is something people make together and launched a process of participatory land use planning across the country that helped to birth soil conservation districts and plans for preventing soil erosion, fertility depletion and protection of family farms.

The rural initiative created precedents for later government initiatives like the programs of the Department of Housing and Urban Development organized by Monsignor Geno Baroni, a leading architect of community organizing, who served as director of the Office of Neighborhood Self Help in the 1970s. In recent years such a view of government as empowering partner has been returning. Carmen Sirianni’s Investing in Democracy details examples. Each June the Frontiers of Democracy conference sponsored by Tufts University’s Tisch College of Civic Life includes many examples. These point to a substantial challenge that is emerging to the “citizen as customer” model of government practice that has long dominated our national thinking.

Citizen Professionals

Citizen Therapists Against Trumpism is organized by Bill Doherty, a leading family therapist and professor at the University of Minnesota and founder of the Citizen Professional Center there. Doherty has helped to develop what is called the public work framework of citizenship in family therapy. His partnerships are based on the idea that the energy of families and communities are the most important resource for addressing many complex problems. Citizen professionals are catalysts and organizers who work with lay citizens, not on them or for them.

The Citizen Therapist group takes this work to a new level. More than 3,000 therapists have signed its manifesto. As a recent Politico article by Gail Sheehy, “America’s Therapists Are Worried About Trump’s Effect on Your Mental Health,” describes, the movement crosses partisan lines. Doherty says the core belief of the group is that “personal and collective agency are at the heart of the work of psychotherapists [and] only flourish in a democracy where we the people are responsible for our common life.” Beyond alerting people to the psychological dangers of “Trumpism,” the movement affirms the public role and responsibilities of therapists in our society. “For me the key starting point is to ask professionals to think about their work as a contribution to the capacity for democratic living,” Doherty told me. He adds that “it’s a startling question for many therapists to think about.”

Other examples of citizen professionalism in action include the reinvigoration of schools, congregations, businesses, businesses unions and health clinics as civic sites. At Augsburg College, where our (Sabo) Center for Democracy and Citizenship moved from the University of Minnesota several years ago, both the nursing and education departments have missions to prepare their students to be change agents – citizen nurses and citizen teachers. A new manifesto of the John Dewey Society, “Educators for a Democratic Way of Life,” builds on stirrings of democratic change in schools and colleges.

Cultural and Intellectual Life

Finally cultural and intellectual trends suggest a “return of the citizen.” The newly opened Museum of African American History and Culture illuminates the agency that black Americans developed and exercised under oppressive conditions. Obama’s foundation, to be launched in Chicago after he leaves office next year, has a central focus on citizen activation. In academia, scholars like Danielle Allen and Doris Sommer, both young professors at Harvard with public educational projects, stress civic agency and civic empowerment. The field of civic studies similarly emphasizes citizens as co-creators of democracy. One co-founder, the late Elinor Ostrom, won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics for her work on citizen governance of common resources like forests and fisheries. Her Nobel Prize address was titled, “Beyond Markets and States.”

Today, few activists believe that Hillary Clinton will fix our problems, and because of that, they are likely to be much bolder in pressing her for change than many were following Obama’s victory in 2008. As Heather McGhee, president of the progressive group Demos, put it on NBC’s Meet the Press last Sunday, “knowing that someone is such a politician … has made it easier for progressives to know how to organize after January. As opposed to what happened when Barack Obama came into office, this is what progressives talk about right now. Nobody wanted to organize against him and push him.”

If such a movement develops, Clinton could turn out to be a partner in something like the same complex ways Lyndon Johnson turned out to be an ally of the civil rights movement. Her own history may make her more open to such developments. She wrote her college thesis on the community organizer Saul Alinsky. In the 1980s, she served as the board chair of the New World Foundation, a funder of grass roots citizen efforts. Now and then in the campaign this year she has pointed to a “government as partner” approach. In the first debate, responding to Trump’s depictions of black communities as hell holes of death and destruction, Clinton talked about the value of supporting civic and economic assets, “the vibrancy of the black church, the black businesses that employ so many people, the opportunities that so many families are working to provide for their kids.”

Clinton alone won’t do the work of democracy for us. All citizens are called to build a movement for a far deeper and wider democracy. But if such a movement develops, Clinton could turn out to be a partner in something like the same complex ways Lyndon Johnson turned out to be an ally of the civil rights movement. That is a positive reason to vote for her beyond staving off a Trump disaster.

The emerging democratic ferment is also a sign of hope in dangerous times.