Civilian Conservation Corps workers, circa 1933. (National Archives)

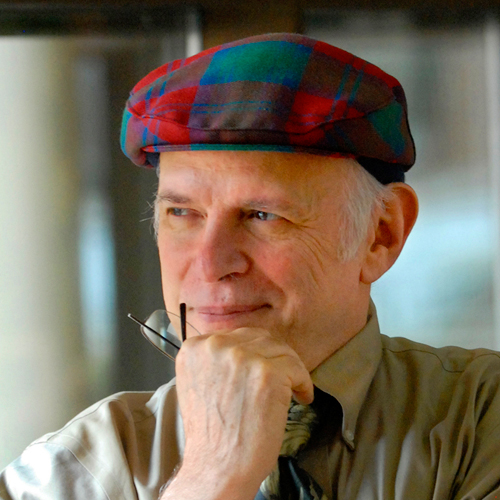

Harry Boyte was only 19 when he joined Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference – a youthful white North Carolinian working as a field secretary and lieutenant to Dr. King alongside equally young black volunteers who formed the front line of the civil rights movement.

The experience taught Boyte that “everyday politics” can change history, and he has spent his adult life teaching and proclaiming that the talents of ordinary people – “from the nursing school to the nursing home” – are essential to democracy. He founded the organization Public Achievement which now empowers young people in more than 20 countries and the Center for Democracy and Citizenship at the University of Minnesota (now the Sabo Center for Democracy and Citizenship at Augsburg College, where he serves as senior scholar in Public Work Philosophy.)

Among his many books my favorites are Everyday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public Life, which one critic said “restores the dignity of real politics” (yes, I will add – even in the Age of Trump), and The Citizen Solution: How You Can Make a Difference. He’s in South Africa right now, and I reached out to him for a response to the polarization and vituperation now roiling American politics. – Bill Moyers

Since the beginning, two narratives have warred for the soul of America. One is the “We’re Number One” America, in which the American Dream is a competition with few winners and others who bask in their reflected glory. This is the America of land grabs, robber barons and get-rich-quick schemes.

The alternative is the story of democracy in which America is a place of cooperative endeavor where people form associations, build schools, congregations, libraries and towns and fight for “liberty and justice for all.”

The novelist Marilynne Robinson was getting at this alternative in her conversation with President Obama last September in Iowa, reprinted in the New York Review of Books. “Democracy,” she said, “was something people collectively made.” Making democracy created a culture of mutual respect.

I learned this understanding of democracy as a young man working for Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in the civil rights movement. In Hope and History, King’s friend and sometime speechwriter Vincent Harding described the movement as “a powerful outcropping of the continuing struggle for the expansion of democracy in the United States.” It showed “the deep yearning for a democratic experience that is far more than periodic voting.”

Today there are new outcroppings of the democracy story but they do not yet merge into a narrative of democracy as a way of life. “We’re Number One” America dominates, coming especially from Republican candidates. It has antecedents.

In 1941, Henry Luce, the publisher of Life and Time magazines, wrote an influential essay called “The American Century.” He was scornful of democracy (“Whose Dong Dang, whose Democracy?” he sneered). He saw the American Dream as meaning opportunities for “increasing satisfaction of individuals.” And he accused Americans of vacillation in the face of the looming war with the Nazis. “The cure is this: to accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and in consequence to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.”

Republican candidates today channel Luce. Marco Rubio’s campaign theme is, in fact, “A New American Century.” Donald Trump pledges to “Make America Great Again” and presents himself as winner-in-chief.

But bashing Republicans isn’t going to revitalize the alternative.

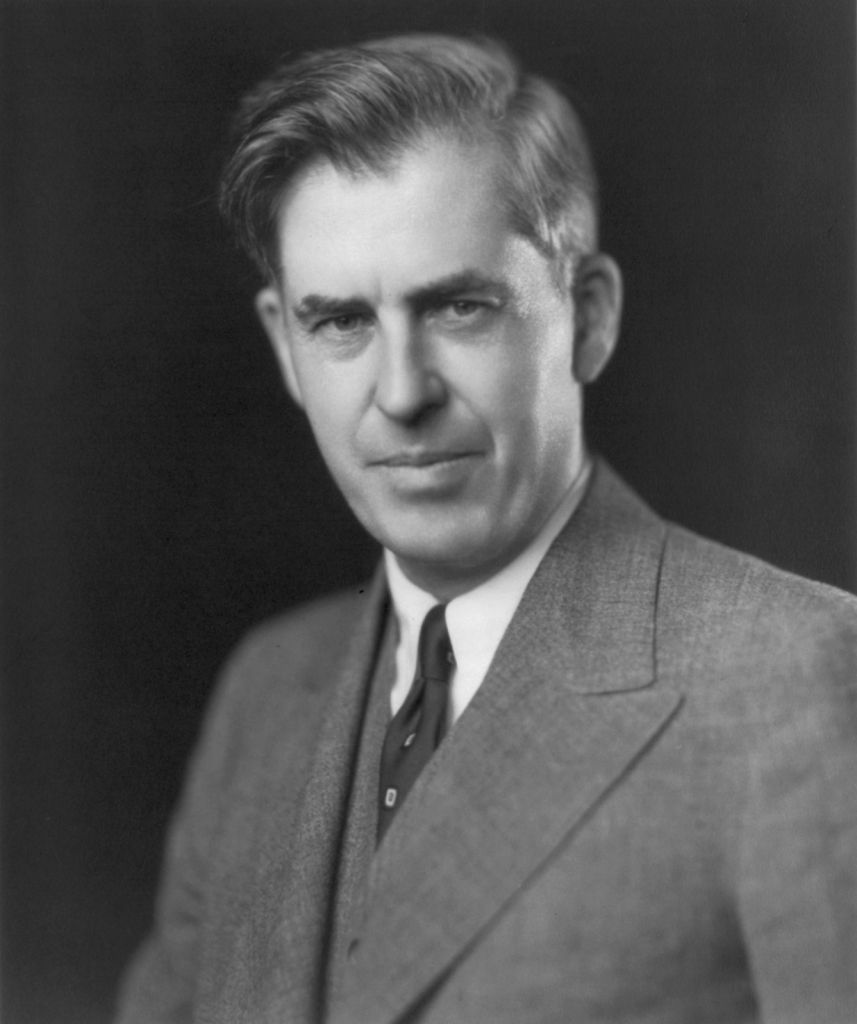

Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president, Henry Wallace, responded to Henry Luce in a speech, “The Century of the Common Man,” in New York, May 8, 1942. Wallace had been a Republican businessman until he became Roosevelt’s secretary of agriculture and then vice president. His family had deep roots in the populist farmers’ movement in rural Iowa.

Henry Wallace (Library of Congress)

Wallace saw the war against fascism as being about democracy, not American dominance. He envisioned an egalitarian democratic post-war world in which colonial empires would be abolished, labor unions would be widespread, poverty would end, and the US would treat others with respect. “We ourselves in the United States are no more a master race than the Nazis,” he said. “There can be no privileged peoples.”

Wallace’s Century of the Common Man drew on the widespread sense of democracy as a way of life built through work that incorporated public meanings and qualities. Citizenship as public work is based on respect for the productive potential of everyone, regardless of income or education, race, religion or partisan belief.

For instance, the men and women participating in programs like the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), involving more than 3 million young men in public-work projects, acted out of practical self-interests, not high ideals. They needed jobs. But their work also had democratic overtones. As people made a commonwealth of public goods, they became a commonwealth of citizens.

The CCC brought people together across differences. As Al Hammer told me in an interview for Building America, a book co-authored with Nan Kari, “The CCC got people like me out into the public. It gave me a chance to meet and work with people different than me from all over the country — farm boys, city boys, mountain boys, all worked together.”

Public work was educative in other ways. C.H. Blanchard observed that “the CCC enrollees feel a part-ownership as citizens in the forest that they have seen improve through the labor of their hands.” Participants often developed a strong sense of public purpose. Scott Leavitt of the Forest Service explained that “there has come to the boys of the Corps a dawning understanding of the inspiring and satisfying fact that they are taking an integral and indispensable part in a great program vitally essential to the welfare, possibly even to the ultimate existence, of this country.”

Government public-work programs were part of many efforts that activated civic energies during the Great Depression. These ranged from unionization of the auto industry to civil-rights struggles, from cultural work in journalism, film, and theater to rural electrification and projects to halt soil erosion.

These efforts extended far beyond government, but government programs could be catalytic, a pattern displayed in New Deal for the Arts, a National Archives exhibit now online. The exhibit celebrates the cultural work of thousands of writers, sculptors, musicians, photographers, painters and others.

Government cultural work provided jobs but also conveyed a message of hope and collective agency that signaled a shift in conventional wisdom. “The people,” seen by intellectuals in the 1920s as the repository of crass materialism and parochialism, were rediscovered as the source of democratic creativity. “The heart and soul of our country is the common man,” said Franklin Roosevelt during the 1940 campaign setting the stage for Wallace.

Cultural workers in and out of government conveyed the story of democracy as a way of life, background for Wallace’s speech. Subsequently the journalist Ernie Pyle’s reports from the front lines of World War II about “GI Joe” generated the wide public perception that the war was about democracy, not superiority. At the end of the war, mainstream commentators regularly called for modesty and expressed appreciation and respect for other nations’ contributions.

The culture of democratic respect has eroded. And as work has come to be seen only as a means to the good life and not of value in itself, the public dimensions of work and recognition of the importance of workers have sharply declined. In Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, Susan Faludi describes the changing identities of men, from African-American shipyard workers to television executives and evangelicals, as work has been devalued. They live “in an unfamiliar world where male worth is measured only by participation in a celebrity-driven consumer culture.” Public visibility of work that contributes to communities and builds the commonwealth has largely disappeared.

Below the surface of anger and division today, a myriad new stories of “making democracy” are growing again. But in this election, no candidate on his or her own is going to weave them into the democracy story. Bernie Sanders, the most vocal about “revitalizing democracy” by challenging the billionaire class, sticks to the basics. “We know what democracy is supposed to be about,” said Sanders in his announcement speech. “It is one person, one vote, with every citizen having an equal say.”

The poet Walt Whitman had a different view. “We have frequently printed the word Democracy,” he wrote in Democratic Vistas. “Yet I cannot too often repeat that it is a word the real gist of which still sleeps, quite unawakened. It is a great word, whose history remains unwritten.”

It is time to recall the greatness of the word democracy. And to reawaken the story.

Correction: Walt Whitman’s quote on democracy appeared in Democratic Vistas, not “Leaves of Grass.”

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.