This is an excerpt from the newly published book Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy, by journalist Dave Daley. This excerpt has been lightly edited for length.

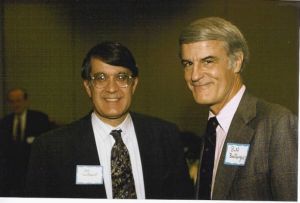

The power behind the throne in Michigan is waiting at the neighboring Grand Traverse Pie Company. Actually, Bob LaBrant might be the genius who first recognized — and fought for — every element of the modern Republican redistricting strategy. LaBrant retired as senior vice president of political affairs for the Michigan Chamber of Commerce in 2014. His hair is now more salt than pepper, but this prescient political thinker is still looking ahead.

“If you have the right talent working, you could almost game-theory a lot of this stuff out and figure out what’s this going to mean not only in, let’s say, 2021, but what it’s going to look like in 2028 as you get toward the end of the cycle,” he muses.

Karl Rove and Frank Luntz might be the Republican strategists and thinkers everyone recognizes, but LaBrant quietly and effectively ran this playbook starting in the 1970s. As a 25-year-old junior executive at the Chamber of Commerce in Appleton, Wisconsin, LaBrant read the Powell Memorandum, penned by future Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell in 1971. Powell wanted the business community to offer a counternarrative to that of Ralph Nader’s consumer coalition and to speak up against what he saw as an anticapitalist attitude on college campuses and in the media.

“Business must learn the lesson . . . that political power is necessary; that such power must be assiduously cultivated; and that when necessary, it must be used aggressively and with determination — without embarrassment and without the reluctance which has been so characteristic of American business.” A new generation of conservative media and pro-business think tanks emerged and laid the intellectual framework for the Reagan revolution. But despite LaBrant’s pleadings, the Chamber of Commerce largely resisted becoming an overt political actor until Tom Donohue took over the national organization in 1997 and made it a serious force. That the national Chamber became one of the most reliable financial supporters of the Republican State Leadership Committee is no accident. LaBrant had spent the previous two decades showing how important an investment in redistricting could be.

Bob LaBrant and Bill Ballenger

The redistricting of the early 1980s was disastrous for Republicans, who found themselves cash-strapped and reliant on whatever legal advice they could get for free, while Democrats got help from the powerful United Auto Workers union. In the wake of this, LaBrant talked his business friends into launching a million-dollar-plus Michigan Reapportionment Fund for the next cycle.

“They had a pro bono lawyer and no money for expert witnesses and they just got their clock cleaned,” he says. “At the time we had 18 members in the delegation and I think it went 12–6 Democrats.”

LaBrant and a Republican colleague, later a judge, sat in a diner and sketched out a plan for raising just over a million dollars. Starting in 1991, “We did have money, we did have lawyers, we did have expert witnesses, we did have computer support. That cycle and then every cycle since that time. That was really important — to plan for redistricting in advance.”

Seven figures for redistricting was a lot of money, especially in 1991. It helped purchase early 386 computers, as well as serious legal firepower.

LaBrant cemented his role as the conservative Zelig of redistricting by directing the challenge that would become Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce, a key Supreme Court case on the road to Super PACs and Citizens United. LaBrant wanted to take on a state law banning corporations from endorsing political candidates, so he pushed the Michigan Chamber to take out a newspaper ad in the Grand Rapids Press backing a local state Senate candidate. The ad was never placed; a judge refused the Chamber’s request to grant an injunction that would have barred any enforcement of the felony provisions for publishing the ad, then upheld the provision a year later, in 1986. But the state Chamber kept pushing, and while they lost before the Supreme Court in 1990 — with a howling Justice Antonin Scalia bemoaning an “Orwellian announcement” and an “erroneous injunction” — the last laugh was LaBrant’s. Twenty years later, the Supreme Court, led by Scalia’s long memory, delayed the Citizens United decision to collect briefs on the Austin case, then swept the precedent aside when it issued the eventful Citizens United ruling.

Perhaps no individual has done more than LaBrant to shape Michigan politics, let alone one who has never held office. LaBrant’s memoir, aptly and hilariously titled PAC Man—self-published in 2014 — does more to explain the GOP blueprint for, and domination of, the last 45 years of campaign finance, redistricting and judicial election battles than any other book. It should be required reading, mostly because there’s no real reason why a lawyer and Chamber of Commerce official should have such outsize influence. But LaBrant recognized Karl Rove’s dictum early — you draw the lines, you make the rules — and figured out how to use the Chamber’s PAC to not just grab a seat at the table, but to help pay to rent the room. And as the rules changed, so did LaBrant. As campaign finance law evolved and his reapportionment fund needed to become a 501(c)4, they just threw the word “institute” on it and called themselves the Michigan Redistricting Resource Institute. “It sounded academic,” he says.

“When you add up all the money you’re going to be spending every two years in legislative races,” he adds, “better to have some input at the beginning.”

“You just needed to get a core group of people that understood what was at stake and be relentless about it,” he says. “Then at times you had to figure out, ‘Okay, what’s the best way to approach this.’ It’s nice to have Bob LaBrant walk through the door, but if you’ve got the Senate majority leader to walk through the door with you, that makes it a lot easier to get somebody to decide to write out a check. That’s nothing new. That’s how power works all of the time.”

— Bob Labrant

In Michigan, lines are drawn by the legislature and are subject to veto by the governor. By 2008, Democrats had beaten back the post-2000 gerrymander and established a bigger House majority on Barack Obama’s coattails. REDMAP had its work cut out, but as their report states: “The effectiveness of REDMAP is perhaps most clear in the state of Michigan. In 2010, the RSLC put $1 million into state legislative races, contributing to a GOP pickup of 20 seats in the House and Republican majorities in both the House and Senate.”

When Rick Snyder was sworn in as governor in 2011, Republicans controlled the redrawing of all 148 legislative and 14 congressional districts. The firewall they built withstood Obama’s re-election. Obama won by just under 10 points in Michigan, and Democrat Gary Peters rode a 20-point landslide into the US Senate, but with the new legislative lines, the GOP retained both state chambers, and Republicans took a 9–5 majority in the congressional delegation.

“We thought we’d have divided control” after 2010, LaBrant says. “We had no idea we could pick up 20 seats in the House. That’s why it was also very important to be involved in the [Michigan] Supreme Court races in 2010″ — in case judges needed to be called in to break a legislative deadlock. So they raised a lot of money and coordinated with GOP groups in DC. “It was almost embarrassing, the amount of money that we were able to ship off to the Republican Governors Association,” he says.

Then they got out the Maptitude and had some fun. First, they needed to connect Detroit and Pontiac in the 14th. That done, it was time to fortify the friendly Republicans and exact a little revenge on Justin Amash, a brash newcomer who was more the style of the tea party than the Chamber.

Rep. Tim Walberg, another Republican, had been defeated in 2008, then recaptured the seat in 2010. “The other goal in redistricting in 2011 was to take the Walberg seat, which had been flipping back and forth with Mark Schauer and Walberg. To solve that you just take Calhoun [County] out of that district and put it in the 3rd District, which was at the time the second most Republican district.”

LaBrant is clear, direct and unapologetic. This is the way the game is played. “This is the most important political decision to be made in the state each decade,” he says, “and to somehow say, ‘We’re going to ignore the politics in this and do something that isolates the process from any political input?’ The only state that has had any success doing that is Iowa.”

Or, as he wrote in his memoir: When you have power, “you exercise it.” When you don’t, you try and remove the other side’s advantage “under the cloak of good government.”

Excerpted from Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy by David Daley. Copyright © 2016 by David Daley. With permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.