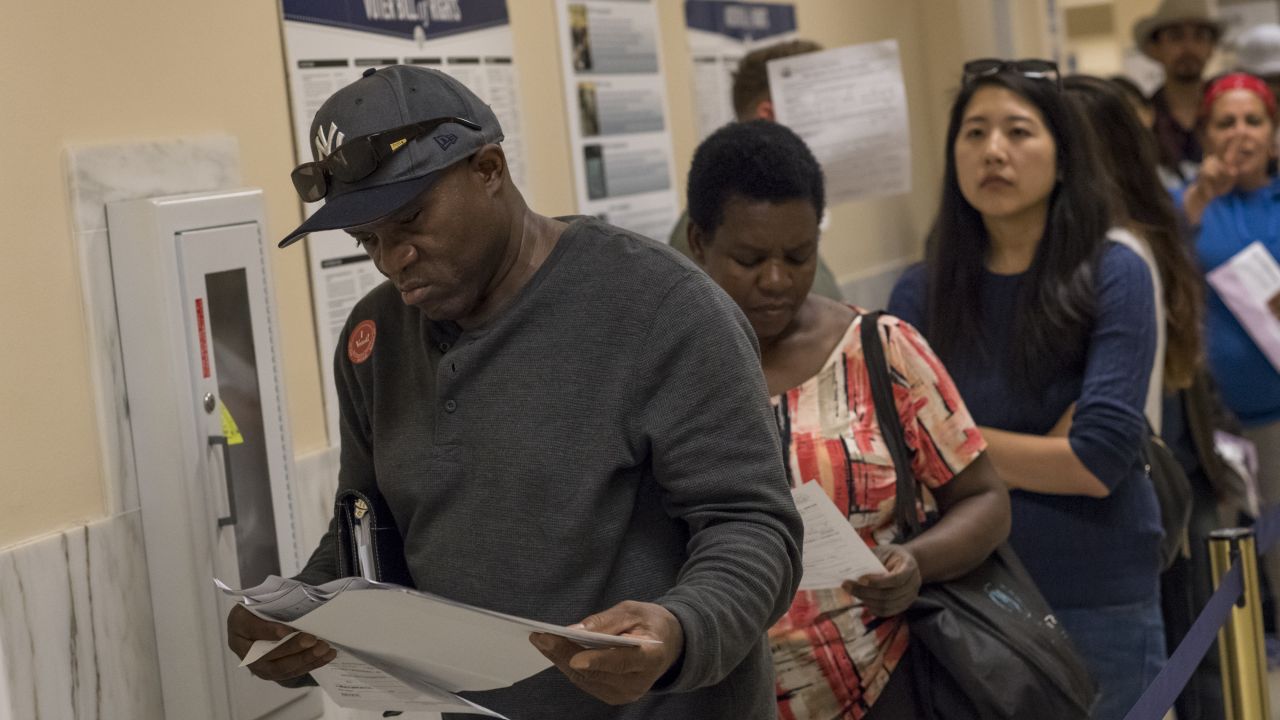

Voters wait in line to cast their ballots at San Francisco City Hall. (Photo by David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at Brennan Center for Justice.

The 2016 election is over, and while much has been written about who voted and for whom, and what the media missed, there has been frustratingly little post-election coverage on the problem of Americans being disenfranchised by predictable and avoidable shortcomings in the ways we administer elections.

Election administrators had to fend off a lot in 2016 before the election even started — claims that elections were rigged, hacks into voter registration databases, out-of-date technology, calls for private citizens to appoint themselves watchers of polling places and politicians passing laws restricting access to the ballot. Each of those issues contributed to problems at the polls. They were compounded by a persistent problem of insufficient resources.

Even before the data comes in to enable researchers to assess the impact of restrictive laws and other issues, there is still ample evidence that too many voters had to contend with:

- Long lines

- Malfunctioning voting machines

- Confusion over voting restrictions

- Voter intimidation

- Voter registration problems

Obviously, 2016 was not the first election in which these problems have occurred — and that itself is a problem.

Below is a sampling of these problems, as reported by news outlets. More information will be available soon, once the results of nationwide surveys and election protection hotlines are released.

Long Lines: “We Have to Fix That,” Still

Despite the president’s oft-quoted admonishment in 2012 that “we have to fix” long Election Day lines, in 2016, hours-long lines were reported during early voting and on Election Day. Long lines were in a diverse range of places, including swing states and non-swing states, states with restrictive laws and those without. Some places that received particular attention this election season were:

- North Carolina, where wait times at one Charlotte polling site exceeded two hours on the first day of early voting and reached three to four hours on the last day of early voting.

- Ohio, where a line to vote early in Cincinnati was a half-mile long.

- Georgia, where a journalist saw three people collapse in an hours-long line.

Other states with reports of hour-plus waits included Arizona, California, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Nevada, among other places.

There are many causes of long lines, including not enough voting sites, inadequate resources and equipment glitches. These problems were visible this year. For example:

- Not enough voting sites to meet demand. In Los Angeles County, voters waited up to four hours to vote early at one of five sites for the jurisdiction’s 5.2 million registered voters.

- Equipment glitches. At one New York City site, a line stretched two blocks outside of a building when only one of six ballot scanners worked for a time.

- Inadequate resources. In Phoenix, a polling site had a two and a half hour wait due in part to having only one computer, one printer and a few poll workers to serve the location.

Too often, resources are not distributed properly, leading to even longer lines for minority voters.

Outdated Voting Equipment Failed Voters

Aging voting machines are a known risk to the functioning of the voting system and public confidence. In 2015, the Brennan Center warned that 42 states use machines that are at least a decade old and approaching the end of their projected lifespans.

There were many reported machine problems across the country in 2012, but even more this year. These problems took a number of forms:

- Broken ballot scanners, which in New York caused delays and provoked complaints from voters.

- “Improperly coded memory cards” that led three-quarters of all the machines in Washington County, Utah to break down. Poll sites offered backup paper ballots — until some of them ran out and told voters to come back later.

- “Vote flipping” on touchscreen direct recording electronic (DRE) machines, which incorrectly register a voter’s choice and feed fears that voting equipment is rigged for particular candidates. This is often the result of age and poor calibration, and was observed this year in at least Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Texas.

Voting machine problems were also reported in Alabama, Maryland, Michigan and South Carolina.

But the problems were not just limited to just machines. This year’s election also presented a relatively new problem from a promising technology: electronic poll books. When functioning properly, electronic poll books can speed up the process for checking in voters. But on Election Day in Durham, North Carolina, electronic poll books failed by incorrectly indicating which voters had already cast ballots, which forced poll workers to check in voters by hand. Eventually, some polling places began turning away voters after running out of the paper forms that were used to check in voters instead. This led to long lines and the extension of voting hours in eight Durham precincts. And in Colorado, the state’s voter registration database shut down and caused rippling disruptions. There were problems with this technology in a handful of places in 2012 (Kansas, Virginia, Maryland and Michigan), but nothing affecting an entire county and requiring the drastic measures used this year.

Voting Restrictions Sowed Confusion

The 2016 presidential election was the first in 50 years without the full protections of the Voting Rights Act, and the first in which 14 states had new voting restrictions. It will take time to assess how many people were impacted by these new restrictions. But in addition to the harms to affected voters, these restrictions also sparked widespread confusion among voters and officials that further kept some citizens from exercising their right to vote.

The most prominent example is Texas, where the country’s strictest photo-ID requirement was found illegal by a federal court on the basis that it was discriminatory. The court-ordered fix for the 2016 election still required voters who could show photo ID without difficulty to do so. But voters who faced a “reasonable impediment” to obtaining ID should have been able to vote after signing an affidavit and showing one of a much longer list of IDs. Unfortunately, this remedy was not properly implemented. There were numerous reports of (a) public education materials in the polling places being incorrect as to what the ID requirement was; (b) poll workers not understanding the ID requirement; and (c) voters not having enough information before Election Day to understand the ID requirements.

In Wisconsin, where a court also modified a photo-ID requirement, confusion on the part of officials may have blocked voters from obtaining documents that could be used to vote. Following Election Day, the executive director of Milwaukee’s Election Commission reported that his city “saw some of the greatest [turnout] declines [from 2012] in the districts [they] projected would have the most trouble with voter-ID requirements.”

And even in places without new restrictions, there was misinformation and confusion. A few of the many examples:

- In Connecticut, poll workers improperly insisted that voters provide ID, misinterpreting the state requirement.

- In New Jersey, signs were posted indicating ID was required when that was not the case.

- Voters were also confused by precinct and moving rules in Ohio.

These challenges extended to those affected by the nation’s felony disenfranchisement laws, which barred over 4.7 million Americans living in their communities from voting in this year’s election because of a past felony conviction. In Virginia, two citizens with restored voting rights had problems casting their ballots perhaps because the voting status of those with previous felony convictions was tangled. The governor issued an executive order restoring voting rights to 200,000, but that order was reversed by a court. Then the governor took subsequent executive action to restore voting rights to approximately 60,000. One voter needed four trips to his polling place before officials allowed him to vote. Another, despite having previously been restored and having voted before, was denied a regular ballot and instead given a provisional ballot. Another, whose voting rights were restored by the governor just this year, described having registered to vote in person and then learning at her polling place that election officials had no record of her. “It was a kick in the gut,” she said.

And elsewhere, citizens with past convictions reported not even knowing that they could vote — like one man in Texas who was never told he was eligible — and an Iowa election official who conceded that some “people think that they just can’t vote” when they actually could.

Problems Not Making the List

Election Day news reports suggested problems in multiple states with those wishing to cast ballots finding out they were not on the voter registration list. This occurred in multiple states, including:

- Virginia, where voters believed that they had registered at the state motor vehicle agency but were not on the list at their polling place.

- In Pennsylvania, where student voters who changed their registration to their school address in Philadelphia were not listed on the voter rolls and a number of students missing from registration lists were reported at Lehigh University.

- California, where people who were registered went missing from records used at voting sites.

- North Carolina, where a judge ruled against a program that removed thousands of voters from the rolls, and numerous individuals reported not appearing on the voter list when they arrived to vote.

Reports of Intimidation Increased

Although incidents of intimidation were not as widespread as some feared given the calls for voters to police other voters, there was an apparent increase in the number of reports of voters being intimidated — a possible increase over the incidents covered by the news in past years.

In some cases, police officers were reported as the source of the intimidation, including in Orange County, Florida, Greene County, Missouri and Denton, County, Texas.

There were also reports of race-based intimidation:

- In Ohio, Somali voters reportedly were harassed and intimidated.

- Elsewhere in the state, billboards advertising that voter fraud is a crime were reportedly placed in primarily African-American areas.

- Conservative activist James O’Keefe reported that he was following and filming individuals giving rides to the polls to primarily to African-Americans in Philadelphia.

- In Michigan, Hijab-wearing voters were reportedly directed away from the polls by a man who others said was singling out racial minorities.

Other disruptions were reported, including a man with a holstered gun in Pima County, Arizona, a loud disruption at a Delaware polling place, voters and poll workers screaming in Pennsylvania and a group blocking the entrance to a polling place until police moved them in Broward County, Florida.

Conclusion

More work and study needs to be done before we can quantify how many voters experienced trouble when voting in 2016, and what impact those problems had on the elections. But we can say that the ways in which elections are administered, including how well they are resourced, can have a negative impact on citizens’ ability to cast a ballot and the confidence the public has in the system. In the upcoming legislative cycles, we have an opportunity to improve our election infrastructure and give American voters the best election process possible.