The Obama administration released strict new guidelines for power plants this morning. They’re a big deal. They’re one of the biggest steps America has taken to combat climate change, ever. Here’s what you need to know.

1. What do they do?

The rules aim to cut US power plant emissions by 30 percent from their 2005 levels between now and 2030. Each state will have different targets to meet, but the national average will be a 20 percent reduction by 2020 and a 30 percent reduction by 2030.

In a speech this morning announcing the regulations, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy emphasized this flexibility. “That’s what makes it ambitious, but achievable,” she said. “That’s how we can keep our energy affordable and reliable. The glue that holds this plan together — and the key to making it work — is that each state’s goal is tailored to its own circumstances, and states have the flexibility to reach their goal in whatever way works best for them,” she said.

In practice, these rules restrict the amount of climate change causing emissions that each state’s fleet of power plants can produce. They encourage (but don’t specifically mandate) a state-by-state cap-and-trade program. The regulations, which will go into effect after a year-long rulemaking process and what is expected to be a bitter political battle (more on that later), come nearly a year after Obama’s speech announcing an ambitious new climate agenda.

These rules follow regulations the EPA released last fall on emissions from plants that will be built in the future — regulations that essentially make it impossible to build coal plants as we know them today.

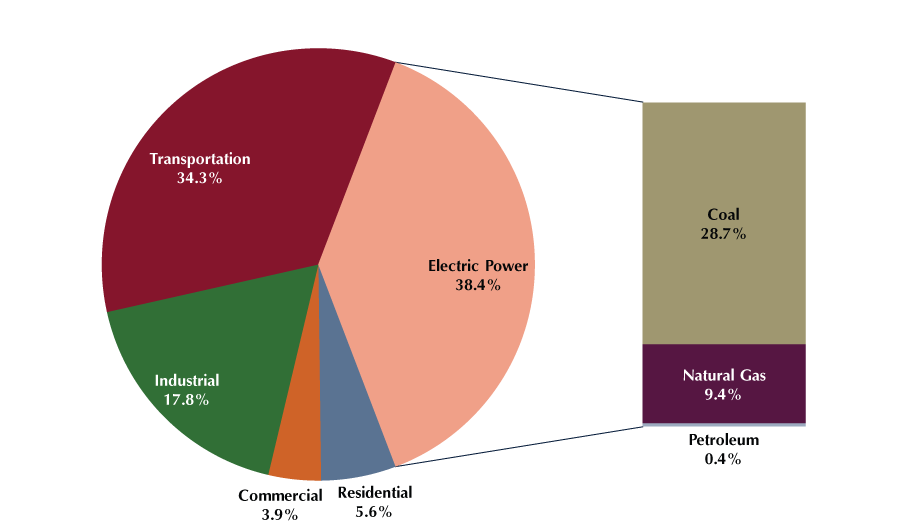

In releasing today’s regulations for plants that are already in operation, the administration is striking at the heart of America’s emissions problem. Between 30 and 40 percent of our country’s emissions come from energy generation. That’s more than any other polluting sector. These rules will regulate all sources of electricity generation, but will most directly affect coal.

Reporters in touch with EPA officials as the plan was being drafted said it was based on a report released last March by the Natural Resources Defense Council proposing a method for America to implement a cap-and-trade scheme. While corporate interests are adept at pushing bills through Congress, environmental nonprofits’ ideas only rarely become law.

2. Why a cap-and-trade-style plan for reductions?

There has long been broad agreement among economists across the ideological spectrum that cap and trade would work to cut emissions; it was conceived by Reagan administration officials and proposed by Republicans during George H.W. Bush’s administration.

In his first term, Obama tried to get cap and trade through Congress, but it died in the Senate when Democratic support buckled under a wave of attacks by tea partiers and the fossil fuel industry.

Last year, Obama responded by pushing new regulations through the EPA under the Clean Air Act. The emissions regulations announced today are the biggest yet.

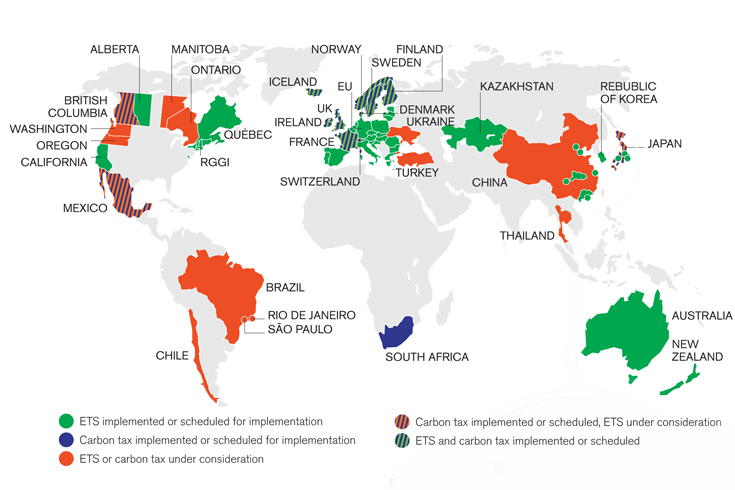

Cap and trade changes the energy market by “capping” pollution limits and requiring polluters to buy carbon offsets. These function similarly to a tax on emissions, making it expensive to burn dirty fuel. We already tax things that are bad for us, such as cigarettes and alcohol. Governments with cap and trade or a carbon tax acknowledge that global warming, and the emissions that cause it, represent a pressing danger to their citizens.

As the map above shows, many countries around the world and a handful of American states already have some form of cap-and-trade system in place. Nine states in the Northeast (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont) established a regional greenhouse gas initiative in 2005. At the time, New Jersey was also a participant, but Gov. Chris Christie has since pulled the state out of the pact. Under this regional plan, large power plants buy pollution allowances to offset the carbon they emit; the proceeds from the allowances are then used to promote sustainability and to reduce rates for low-income consumers. Emissions in the region dropped 40 percent from 2005 through 2012; consumers’ electricity prices fell at the same time. California also has a cap-and-trade program that started last year.

Both programs, The New York Times’s Coral Davenport pointed out, bear the signatures of Republicans: “Mitt Romney, the 2012 presidential nominee and former Massachusetts governor, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, the former California governor.”

As governor of Massachusetts, Mr. Romney was a key architect of a cap-and-trade program in nine northeastern states, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. He worked closely at the time with a top Massachusetts environmental official, Gina McCarthy, who today is immersed in the Obama administration’s new rule as the administrator of the E.P.A. Mr. Romney later disavowed the regional cap-and-trade program.

Both programs hope their successes can be examples for other states after today’s proposed rules become law. Pennsylvania’s Democratic nominee for governor, Tom Wolf, has said his state will join the Northeast Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative if he is elected.

Today’s rules give the states flexibility in how they will make reductions. They can change what happens in their power plants, they can change the power sources themselves, they can change the grid or they can attempt to reduce consumers’ demand. (In industry jargon, states are free to use “fence-line changes,” “fleet-wide changes” or “system-wide changes” to meet their emissions targets.)

3. Will industry groups fight back?

Of course. Over the next year, before the rules go into effect, money is expected to pour into Washington to influence the final standards. Lots and lots of money. The fight, and the rhetoric, will be bitter.

New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait predicted it will be comparable to the vicious fight over Obamacare. “The plan both fulfills a generational goal of liberal social policy and stokes conservative fears of an unaccountable executive. It’s Obamacare and Benghazi rolled into one,” he wrote.

In fact, shots had been fired even before the rules were released. The Chamber of Commerce released a report last Wednesday attempting to show that the new rules will devastate the American economy. It placed the cost at $50.2 billion per year in constant dollars between now and 2030. But as Paul Krugman noted, “real GDP over the period 2014-2030 will be $21.5 trillion. So the Chamber is telling us that we can achieve major reductions in greenhouse gases at a cost of 0.2 percent of GDP. That’s cheap!”

In fact, cap-and-trade programs will likely spur the economy in other ways, as McCarthy noted in her speech this morning. “Climate action doesn’t dull America’s competitive edge — it sharpens it,” she said. “It spurs ingenuity and innovation.”

The Supreme Court ruled in a 2007 decision, Massachusetts vs. EPA, that the agency has the authority to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant that endangers Americans. But the ruling was broad, and industry lobbyists and lawyers will look for ways the new rules fail to align with it. (Forbes’ Daniel Fisher has a good overview of some arguments they might make.)

4. This could help the US become a global leader on climate change.

Right now, we aren’t. We create the second most climate change-causing emissions in the world (next to China), and our reticence to join any international agreements has kept the discussion on hold worldwide.

Chinese officials insist that they shouldn’t have to take the first steps in cutting emissions, because theirs is a developing economy. (Historically, the US has done more to contribute to climate change and was only recently surpassed by China in emissions produced.) Chinese officials want America to take the lead in cutting emissions, and the regulations announced today are a major step in the right direction. Christiana Figueres, the executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the body’s top climate change official, said these rules might be enough to spur action from China and India, which is another huge polluter with a developing economy. Today’s rules would also allow America to meet Obama’s promise at the 2009 Copenhagen climate summit to reduce emissions substantially by 2020.

5. What’s next?

The final version of the rules will be out in June 2015.

At first, the cost of our energy might rise. Some energy providers are already raising prices in anticipation of the regulations.

But by planning ahead, finding ways to produce more clean energy and reducing the overall demand for energy, state governments and utilities can minimize those increases, or prevent them from happening at all.

And not taking action to avert climate change would, of course, be far more expensive. As Justin Gillis and Henry Fountain note in The New York Times, the international community still has a long, long way to go to avert the worst effects of global warming. And most Americans are ready for our government to act.

The rules may be here just in time. For the first time since the start of the recession, US emissions are rising again.