A version of this essay will appear in an upcoming issue of The Nation, focusing on the Supreme Court. It will be available on newsstands Sept. 20, 2012.

Why a special issue of The Nation devoted to the Supreme Court? Because with partisan gridlock paralyzing both the president and Congress, the court has more than ever become “the decider” — the most powerful branch of government, and one at the center of a controversy whose outcome may shape the course of democracy for generations to come.

By a paradox both historical and constitutional, the political appointees on the Roberts Court will never have to answer for their decisions to voters like you and me. Nor to the president or Congress: once they are confirmed, the Supreme Court’s justices, like all federal judges, serve for life or “good behaviour.”

The Constitution’s framers meant to secure the court against political pressure from the electorate and arbitrary dismissal of its members from on high by presidents dissatisfied with their decisions. As the third branch of the new national government — one whose powers were to be divided to block overreach by any one of them — the court would be equal to the executive and legislative arms, even though the president appointed its members with the concurrence of the Senate.

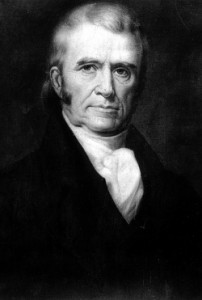

That changed dramatically when John Marshall became the fourth chief justice in 1801, shortly before Thomas Jefferson took office. The two brilliant men were bitter rivals, members of opposing parties. Marshall was a Federalist, Jefferson a Republican (no kin to the present GOP). So the supposedly neutral Court has been thrown since its infancy onto the partisan battleground, where it remains to this day.

In a landmark case in 1803, Marshall refused to apply a 1789 law giving Congress a power not strictly authorized in the Constitution and therefore “unconstitutional.” With that decision, the court was no longer merely equal to the other two branches. It had become superior — the last word on how the Constitution should be interpreted — and its lifelong members would never risk their jobs, no matter how much they fell out of step with changing times and values.

Marshall served for 34 years, exercising deft leadership and cementing two of his most cherished concerns into constitutional law. One was the supremacy of the national government over the states; the other, a hospitality to the interests of the manufacturing, commercial and financial corporations whose wealth swelled as the country expanded. Various decisions that he handed down sheltered them from state regulation, either by invoking the clause of the Constitution that forbade impairing the obligation of contracts, or by insisting on exclusive federal primacy in regulating interstate commerce.

During the Gilded Age the identity of the justices changed, but the court’s romance with big business flourished. Reformist efforts to reconcile democracy and industrialism were generally rebuffed. The court endowed corporations with personhood under the Fifth and 14th Amendments — which guaranteed the rights to life, liberty, and due process of law — and interpreted the commerce clause so as to strike down legislation that tried to inflict on capitalism such “socialistic” and un-American horrors as forbidding the employment of small children in factories. The court also looked unfavorably on limiting work hours in especially grueling or dangerous and disease-causing jobs; on breaking up the powerful trusts that steamrollered small competitors out of existence; on taxing incomes progressively; and on the right of workers to organize and strike. The court’s mantra became “Just say no” to anything that smacked of progressive reform — including efforts to ameliorate the real-life misery of everyday people. By the turn of the twentieth century, populist and progressive forces were calling in vain for constitutional amendments or new legislation to end judicial review, but the majority on the court remained hostile to democracy.

Even the national emergency of the Great Depression did not budge the court’s majority, which began to invalidate the building blocks of the New Deal. But fortune and a Democratic landslide in 1936 broke the court’s blockade. After Roosevelt tried and failed to add six extra justices, a series of resignations and deaths created vacancies that he quickly exploited. Eventually, in his 12 years in office, Roosevelt named not six but eight new justices. After almost 130 years of shielding those whom Roosevelt dubbed “economic royalists” from the effects of human suffering and popular discontent, the court swung left, where it more or less stayed for some four decades, including more than 20 years of Republican administrations.

Under Chief Justice Earl Warren, an Eisenhower appointee, a shower of socially liberal decisions refreshed the roots of “liberty and justice for all”: Brown v. Board of Education, Baker v. Carr, Griswold v. Connecticut, Miranda v. Arizona, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. These rulings in the aggregate ended segregation, decreed “one person, one vote” representation in state and federal election districts, guaranteed the right of couples to choose contraception, strengthened the rights of criminal suspects against governmental coercion, and shielded the freedom of the press from libel prosecutions. In the generally liberal atmosphere of the 1960s, frustrated conservatives could only grind their teeth and flaunt their opposition to changing values and mores with “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards and bumper stickers, but no attempt to do so ever made it to the floor of Congress.

But the days of dominant social liberalism were numbered. The last important victory scored by the shrinking number of progressive Democrats in the Senate was to defeat Ronald Reagan’s nomination of Robert Bork to the court in 1987. In his confirmation hearings, Bork proved himself a vigorous and intellectually skilled opponent of almost every one of the court’s rights-guaranteeing decisions for the preceding 50 years. His appointment would have pushed the court toward a resurrection of the good old days when the captains of industry ruled politics and devout practitioners of the dominant Christian orthodoxy governed the lives of others.