WASHINGTON, DC - FEBRUARY 16: Reporters attempt to pose questions to U.S. President Donald Trump during a news conference announcing Alexander Acosta as the new Labor Secretary nominee in the East Room at the White House on February 16, 2017 in Washington, DC. The announcement comes a day after Andrew Puzder withdrew his nomination. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Of all the incredible statements issuing from the fantasy factory that is the imagination of Donald Trump, the one he recently made in a speech to graduates of the Coast Guard Academy, that “no politician in history — and I say this with great surety — has been treated worse or so unfairly” sets an unenviable record for brazen ignorance plus a toxic mix of self-aggrandizement and self-pity. In his eyes, the most villainous persecutors are the mainstream “fake news” organizations that dare to oppose his actions and expose his lies.

So, having already banned nosy reporters from news corporations that he doesn’t like, branded their employers as enemies of the nation and expressed a wish to departed FBI Director James Comey that those in the White House who leak his secrets should be jailed, why should there be any doubt that he would, if he could, clap behind bars reporters whom, in his own cockeyed vision, he saw as hostile? His fingers itch to sign an order or even better a law that would give him that power. Could he possibly extract such legislation from Congress?

Such a bill might accuse the press of “seditious libel,” meaning the circulation of an opinion tending to induce a belief that an action of the government was hostile to the liberties and happiness of the people. It also could be prohibited to “defame the president by declarations directly or indirectly to ‘criminate’ his motives in conducting official business.”

With a net that wide, practically anything that carried even the slightest whiff of criticism could incur a penalty of as much as five years in jail and a fine of $5,000. Just for good measure, couple it with an Act Concerning Aliens, giving the president the right to expel any foreign-born resident not yet naturalized whom he considers “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States” without a charge or a hearing.

How Trump would relish that kind of imaginary power over his enemies!

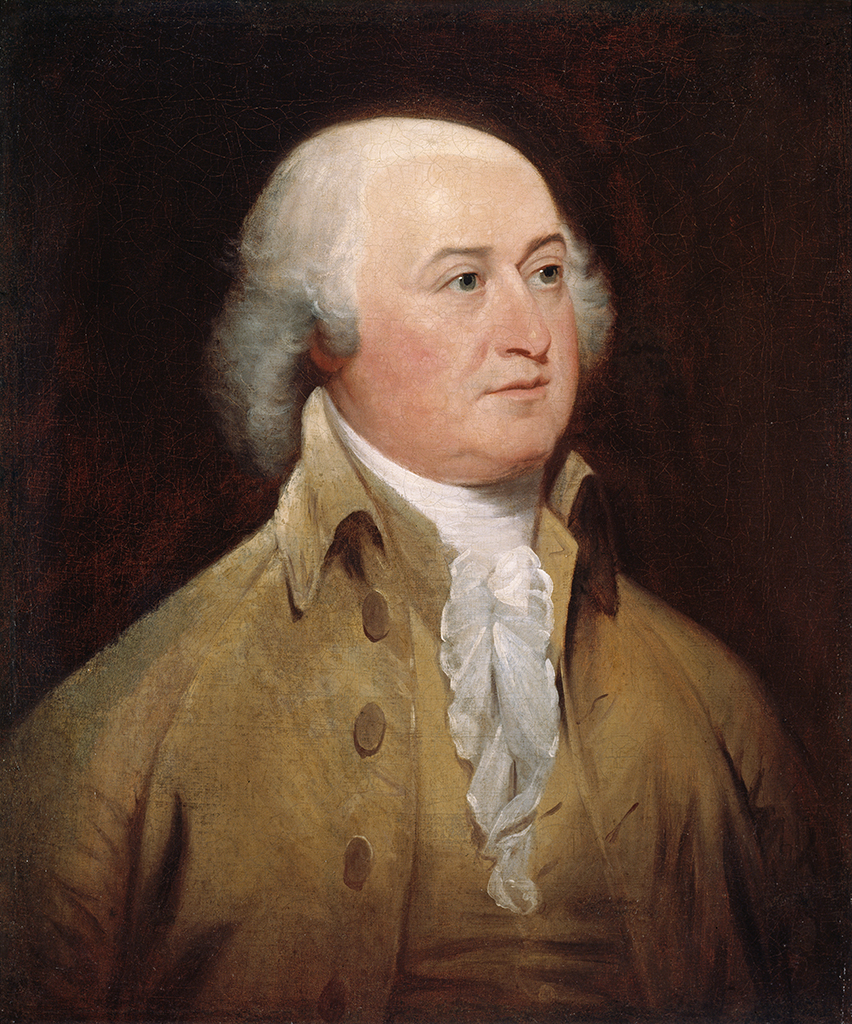

I didn’t make up those words. They are part of actual laws — the Alien and Sedition Acts, passed in the summer of 1798 and signed by John Adams, our second president and titular leader of the conservative Federalist Party. Men were actually tried, imprisoned and fined for such “sedition.” If anyone believes that under the First Amendment gagging the media can’t happen here, the answer is that it already has.

John Adams by John Turnbull, 1793. (National Portrait Gallery)

How did it happen? Just as it could happen again today — in the midst of a “national emergency.” In Adams’ day, it was a war scare with France that produced a flurry of “stand behind the president” resolutions, a hugely expanded military budget (including the beginnings of the US Navy), demonstrations of approval in front of Adams’ residence and a conviction among the Federalists that members of Congress who talked of peace — namely the “Republicans,” the pro-French opposition party who at that time were the more liberal of the two parties, “[held] their country’s honor and safety too cheap.”

In other words, just the kind of “emergency” that could be produced at any time in our present climate by a terrorist attack here at home — genuine, exaggerated or contrived — and pounced upon by the man in the White House.

Do I exaggerate? Read the chilling report of the April 30 interview between Jon Karl of ABC News and Trump chief of staff Reince Priebus, who said the president might “change libel laws” so he could sue publishers. When Karl suggested that this might require amending the Constitution, Priebus replied, “I think it’s something that we’ve looked at, and how that gets executed or whether that goes anywhere is a different story.”

This is reality. A lying president aspiring to become a tinpot dictator is making his move. It’s time to be afraid, but not too afraid to be prepared.

Let’s briefly flash back to 1798. In the bitter contest between Federalists and Republicans, their weapons were the rambunctious, robust and nose-thumbing newspapers of the time, run by owner-editors and publishers who simply called themselves “printers.” They weren’t above dirtying their own hands with smears of ink, nor was there any tradition of “objectivity.” A British traveler of a slightly later time wrote that “defamation exists all over the world, but it is incredible to what extent this vice is carried in America.”

Nobody escaped calumny, not even the esteemed father of his country. Benjamin Franklin Bache, Republican editor of the Philadelphia Aurora, commented as George Washington departed office that his administration had been tainted with “dishonor, injustice, treachery, meanness and perfidy… if ever a nation was debauched by a man, the American nation has been debauched by WASHINGTON.”

Bache also had harsh words for “old, bald, blind, querulous, toothless, crippled John Adams,” sounding very much like a pre-dawn Trump tweet aimed at some critic of His Mightiness. You might not find that kind of personal invective now in The New York Times or The Washington Post, but it’s familiar on right-wing talk radio and would sound at home coming from the mouths of Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity or Ann Coulter. The mode of dissemination changes; the ugliness at the core is unchanged.

Stung and furious, Adams and his Federalist supporters in Congress pushed the Sedition Act through Congress, though by a narrow majority. But could it survive a legal challenge from the Republican minority under the First Amendment’s guarantee of press freedom? The Federalists answered with a legal interpretation that the guarantee only covered “prior restraint,” which meant that a license from a government censor was required before publication of any opinion. Once it actually emerged in print, however, it had to take its chances with libel and defamation suits, even by public officials. Today, “prior restraint” is judicially dead, but the question of who is a public official and can be criticized without fear of retaliation in the courts continues to produce litigation.

But in 1787 argument made little difference. With the trumpets and drums of war blaring and thundering, the Constitution, as usually happens in such times, was little more than a paper barrier. Some provisions were added that would help the defense in a prosecution under its provisions. Moreover, the act was ticketed to expire automatically on March 3, 1801, the day before a new president and Congress would take office and either renew the law or leave it in its grave — which is precisely what happened when Thomas Jefferson and the Republicans eventually won the 1800 election.

Nevertheless, during its slightly more than two years in force that produced only a handful of indictments, the Sedition Act did some meaningful damage. It produced what Jefferson called a reign of witches — harmful enough to prove it was a travesty of justice, but not enough to become a full-blown reign of terror like the “disappearances” and executions of modern tyrannies.

The act never succeeded in its purpose of muzzling all criticism of the government, and in fact worked to the contrary. The toughest sentence — 18 months in jail and a fine of $450 — a huge sum in those days when whole families never saw as much as $100 in cash — was imposed on a Massachusetts eccentric who put up a “Liberty Pole” in Dedham denouncing the acts and cheering for Jefferson and the Republicans. Other convictions for equally innocuous “crimes” defined by zealous prosecutors as sedition inflicted undeserved punishment by any standard of fairness. But two were especially consequential thanks to the backlash they produced.

After the House failed to expel Matthew Lyon for the “gross indecency” of spitting tobacco juice at Roger Griswold, the latter sought justice by attacking Lyon on the House floor (then located in Philadelphia’s Congress Hall) with a cane. Lyon defended himself with a pair of fire tongs. Commemorating the row between representatives, this 1798 etching includes verse describing the scene, including the detail that Lyon “seized the tongs to ease his wrongs.” (US House of Representatives)

One involved Matthew Lyon, a hot-tempered Vermont congressman, who ran a newspaper in which he accused Adams of a continual grasp for power and a thirst for ridiculous pomp that should have put him in a madhouse. For that he got a $1,000 fine and four months of jail time in an unheated felon’s cell in midwinter. But numerous Republican admirers raised the money to pay his fine. A senator from Virginia rode north to personally deliver saddlebags full of collected cash. Lyon even ran for re-election from jail in December and swamped his opponent by 2,000 votes. His return to his seat in the House was celebrated joyfully by Republican crowds.

Jedidiah Peck from upstate New York was also indicted for his heinous offense of circulating a petition for the repeal of both the Alien and Sedition Acts. At each stop in his five-day trip to New York City for trial, the sight of him in manacles, watched over by a federal marshal, provoked anti-Federalist demonstrations. His case was dropped in 1800, and he was also easily re-elected to his seat in the New York assembly.

In fact, the entire Republican triumph in that year’s election was in good part a backlash to the censorship power grab of the Federalists. Literate voters of 1800, kept informed by a vigorous press, were not going to put padlocks on their tongues or take Federalist overreach lying down. Maybe it was from ingrained love of liberty or plain orneriness, or maybe because they were tougher to distract than we their heirs, beset by a constant barrage of entertainment, advertisements and other forms of trivial amusements.

Because that stream of noise is constant and virtually unavoidable by anyone not living in a cave, we are vulnerable to the tactic of the unapologetic Big Lie. If Trump keeps repeating “fake news” over and over at every exposure of some misdemeanor, eventually the number of believers in that falsehood will swell.

Genuine trouble is at our doorstep. If that statement from Reince Priebus is taken at face value, our bully-in-chief is looking for nothing less than control of the court of public opinion through management of the media by criminalizing criticism — all behind a manufactured façade of governing in the name of the people.

With the example of 1798 before us, we need to resolve that any such effort can and must be met with the same kind of opposition mounted by that first generation of Americans living under the Constitution. If we want to be worthy of them, we need to use all our strength and resolution in deploying tactics of resistance. We need to fill the streets, overwhelm our lawmakers with calls and letters, reward them with our votes when they check the arrogance of power and strengthen their backbones when they waver. Any of us who gets a chance to speak at public gatherings and ceremonies should grab it to remind the audience that without freedom of speech, assembly and protest there is no real freedom. If the First Amendment vanishes, the rest of the Bill of Rights goes with it. And we’re dangerously close.