In my first column, I introduced the concept of VIA (Verification, Independence and Accountability) when defining news. Last time, we dug deeper into the concept of verification. Now we focus on independence.

We encounter many different types of information daily. In the past, it was pretty easy to distinguish one type of information from another. When you watch a television drama, for example, you know the difference between the actual show and the commercials (that is, if you aren’t watching it on Netflix or other streaming service). The distinction is pretty obvious. However, with more of us consuming more media on the internet, it’s becoming more difficult to separate the types of content we’re seeing.

Every Facebook post has essentially the same visual characteristics: a large image (if one is attached to the post) and a line of text, which is displayed in the news feed. It also features a “like” button, a comment link and a link to share the piece. The primary distinctions are its content (which for written content can’t be displayed fully), links to another page and the creator, who is identified by name and a small picture in the upper left-hand corner. Below are two posts that came from my personal Facebook feed.

The first is a news story from NPR. The image and the headline probably catch your attention — especially if you’re a fan of Habanero peppers — and might lead you to click to find out more. The second post is an advertisement. At first glance, how would you know that? It looks pretty much the same, with the same characteristics, and even includes a video from a local news show. I’ve seen posts featuring a news story from our local CBS affiliate station in Chicago, and even I paused for a second to figure out what exactly it was. The internet has blurred the lines between categories of information, and most importantly, between journalism and everything else.

In our News Literacy course, we help students understand the different categories of information they encounter every day. We define “Information Neighborhoods” primarily by the piece of media’s main purpose. Here are those categories and their intended purposes:

- Advertising — Persuade the audience to purchase a product.

- Publicity — Increase the audience’s awareness of a brand, product or individual.

- Entertainment — Give the audience pleasure, diversion or amusement through storytelling and performance.

- Propaganda — Persuade an audience’s position through deliberate misinformation spread widely to harm a group, institution or nation, among others.

- Raw Information — Serves multiple purposes, but has not yet been examined or verified.

- Journalism — Inform the audience on information of public interest using the journalistic process of verification.

Understanding each of these neighborhoods is important because the lines that separate them are often ill-defined. In this blurring, content creators sometimes adopt the appearance of other types of information to try to increase their own credibility.

A prime example is “native advertising” or “sponsored content.” The internet and social media have created major business challenges for all traditional news outlets — newspapers, news magazines and TV and radio news departments. All of them have relied heavily on advertising, but new media have caused advertising revenues to plummet. Worse still, new media consumers simply don’t like seeing ads, so news outlets disguise them as something that looks like news but is actually just a sophisticated type of promotion.

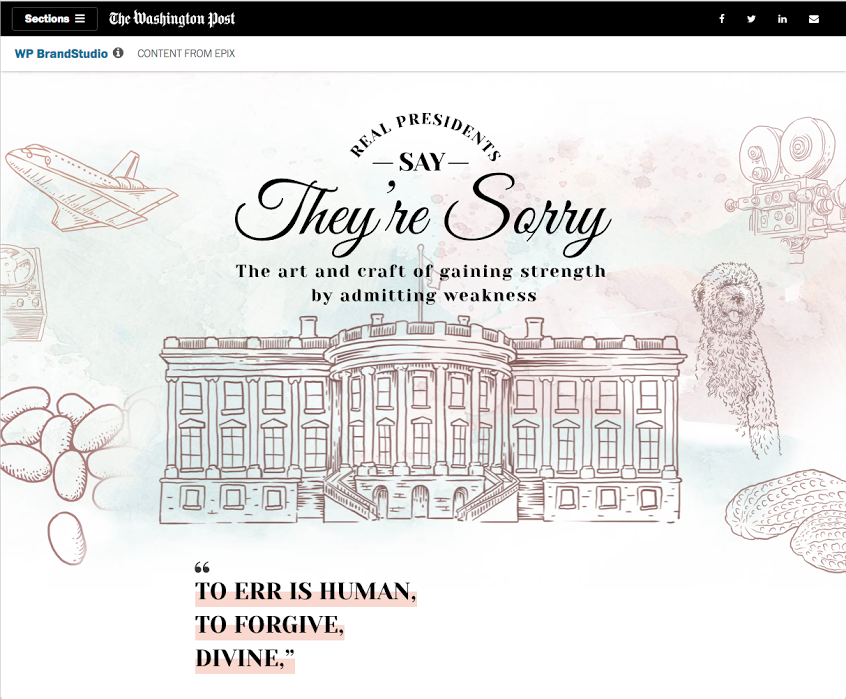

The good news is that reputable news outlets always label native ads to differentiate them from straight editorial content. In the case of this piece of native advertising below from The Washington Post’s “Brand Studio,” the label “WP BrandStudio — Content from EPIX” is placed at the top.

The bad news is that many studies have shown that even sophisticated consumers either do not see those labels — they are often in very light letters — or do not understand that the label means this information might be verified and accountable, but it is definitely NOT independent. Recent research from the Stanford Graduate School of Education, for example, finds that young and otherwise digital-savvy students can easily be duped. They have a difficult time distinguishing news articles from advertisements and identifying the source of information they encounter.

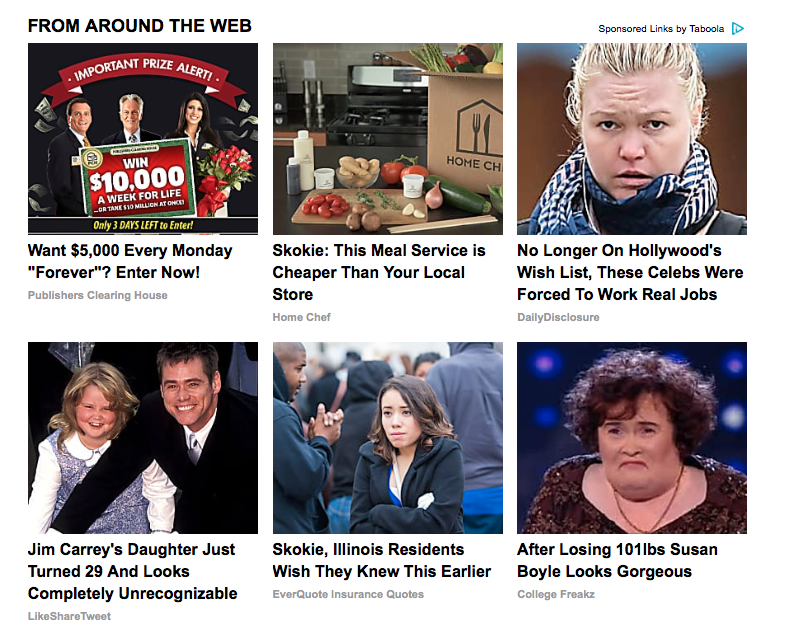

“Promoted stories,” as in the image below, are advertising that can sometimes appear next to or below editorial content on a website, usually from advertisers like Outbrain and Taboola, among others.

A screenshot of sponsored links below a story from the Chicago Tribune’s website

These are simple headlines, known as clickbait, styled to look like stories that might interest its audience and garner a click from the user. These clicks translate into what are known as “impressions” (or views), which lead to higher advertiser revenues. Publications are paid by advertisers to garner user clicks.

In both cases, the news outlet allows advertisers to borrow its credibility with consumers, a credibility whose foundation is built on its independence. Consumers expect news organizations not only to be accountable for and verify everything they publish; they also expect that news outlets will present information meant solely to inform its audience on the issues of the day, not to sell them a product, service or idea. For news outlets to be credible, they must continually show their audience that they maintain the highest standards of independence in what they publish.

Clearly, the challenges created by new media require new approaches to spotting unreliable information masquerading as journalism. Here are a few ways you can spot sponsored content that poses as news:

Look for fairness. Has more than one side of the story been presented? For example, a native ad for a new iPhone can be made to look like real journalism, but does the article only contain positives about the product? Have you ever known of a product that had no downsides? An independent news outlet will present both positives and negatives and will quote outside experts and even competitors.

Check for continuity. When encountering stories about controversial topics, check them against other news outlets. Look to see if the basic facts are the same at each outlet.

Beware of selling tactics that wear the veil of news. This is particularly relevant for headlines that contain exaggerations or that ask unusual questions. Also, always steer clear of articles with headlines that are all in CAPITAL LETTERS. It’s also a good practice to check any headline against the story’s content. If a headline is not substantiated by the article itself, that’s a good sign it’s unreliable.

Using a combination of these tactics can help you build the capacity to spot misleading information masquerading as news. To learn more about this and other topics related to news literacy, join our online “Making Sense of the News” on Coursera. See you next time.