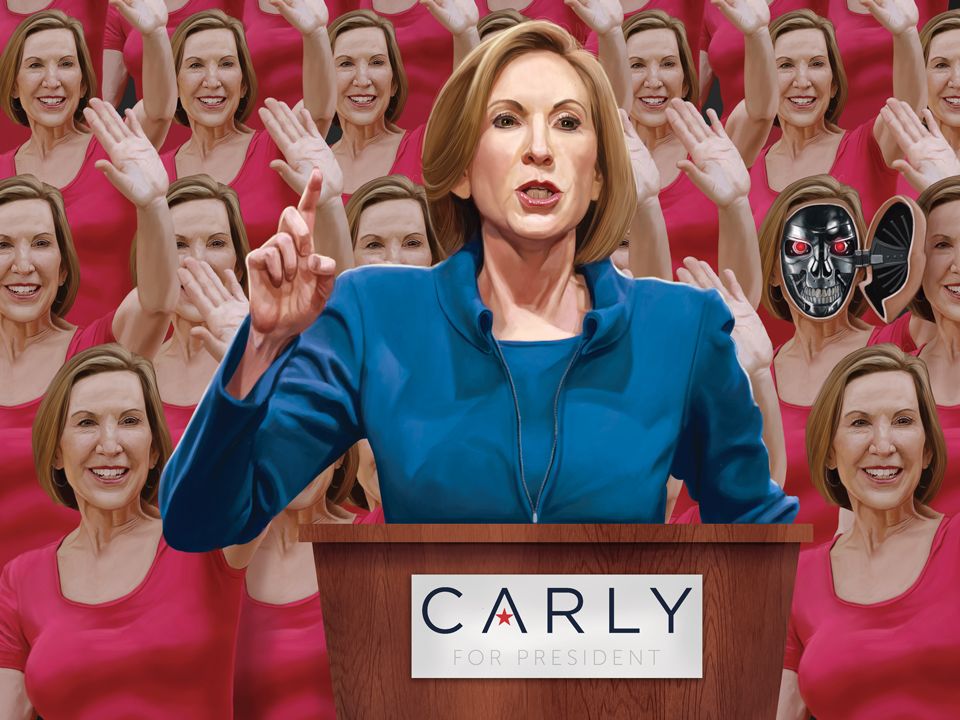

Illustration by Mark Hammermeister

This post originally appeared at Mother Jones.

One Evening in October, former Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina, Republican candidate for president, hit the stump at an elementary school in Windham, New Hampshire. It was one of those idyllic New England fall nights, just cool enough for a sweater, and along the winding road to the school’s entrance the leaves were beginning to turn. Volunteers in red T-shirts and navy blazers scurried around with clipboards, collecting tickets and handing out flyers by the door. Inside, they taped campaign signs beneath the basketball hoops, and ushered guests to their seats. Girl Scouts with badge-covered vests and glittering headbands sat cross-legged on the floor in front of senior citizens, whose white hair bobbed above the crowd like the Monadnocks in winter. The tableau was almost Rockwellian.

But unbeknownst to the voters in the room, they were guinea pigs in one of the most brazen experiments in modern politics. The people with the clipboards to whom they’d just given out their names, addresses, and phone numbers weren’t with the Fiorina campaign, despite what some of these volunteers had strongly implied. True, they did all seem to be wearing CARLY T-shirts and CARLY stickers, but technically, it was an acronym. When I asked a man with a clipboard what it stood for, he said he wasn’t authorized to answer.

In fact, the event was run by a super PAC, one to which Fiorina has, to an unprecedented degree, outsourced virtually every aspect of her operation but the stump speech itself. Signs, shirts, stickers, phone calls, canvassing, event staffing, ads, grisly rapid-response abortion videos — even a documentary, Citizen Carly, which it screened in four states. Super PACs can accept unlimited contributions from individuals and corporations, but they are prohibited from naming themselves after a candidate. So after the Federal Election Commission threatened the group with penalties last summer, the super PAC formerly known as “Carly for America” became “Conservative, Authentic, Responsive Leadership for You and for America” — that is, CARLY.

Federal law also prohibits super PACs from coordinating with political campaigns. The way CARLY and Carly navigate this is a bit more complicated. Traditionally, campaigns pick and choose which towns they want to visit, select a venue, and book an event. Fiorina doesn’t usually do that. Instead, she accepts invitations from hosts, usually supportive chamber of commerce types, who’d like to hear her speak. She then posts the event on a Google calendar that’s publicly accessible to anyone who knows where to look. CARLY sees an event has been posted and coordinates with the host about running it. So Carly coordinates with the host, and the host coordinates with CARLY, but CARLY does not coordinate with Carly. Got it?

In a normal year, CARLY’s end run around election laws might be a scandal, but 2016 is not normal. Billionaire Donald Trump led the GOP field for nearly four months before running his first TV ad; his biggest campaign expenses have included baseball hats and T-shirts. With the Iowa caucuses fast approaching, Dr. Ben Carson, his closest competitor, took a month off to sell his new book. But his campaign continued to raise and spend vast sums of money through a direct-mail fundraising tactic that gave more than half of every dollar raised to consulting firms. Hillary Clinton is such a magnet for money her outside group has an outside group. (Citing a loophole that exempts an organization from being regulated by election law so long as it only exists online, Clinton is even coordinating with one of her super PACs.) The only campaign that would have even been legal eight years ago belongs to a 74-year-old socialist.

This shake-up stems from a seismic event that shook the campaign finance system to its core: In 2010, a series of court rulings, including the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, gutted campaign finance laws and opened elections to a flood of outside cash. The result was that by the next election in 2012, megadonors such as casino magnate Sheldon Adelson could prolong the life span of a candidate like Newt Gingrich for months by funding an independent super PAC. That system has become ever more intricate over the last four years. Today we have not just parallel campaigns such as Fiorina’s, but parallel parties — clusters of donors untethered from the rest of the political process selecting and funding candidates autonomously. As if to underscore this new phenomenon, the first GOP candidate forum of the 2016 campaign was held not by the RNC, but by the billionaire Koch brothers, whose donor network plans to spend nearly $1 billion to get its preferred candidate elected.

The reality of what it means to run for president is being turned inside out in ways that are both more democratic and astonishingly less so. You can bypass traditional gatekeepers of power — provided you can find a sugar daddy to pay for it. But the flood of money and outside groups has also fueled a backlash. It has inflamed voters’ skepticism of political elites beyond the usual clamoring for a Washington outsider, and created an opening in which unorthodox candidates can thrive by running unorthodox campaigns. But that, too, comes with a catch. Those candidates aren’t shirking money in politics; they’re just acquiring it and using it in new, and even deceptive, ways. The result is an increasingly surreal landscape at every level, in which no candidacy is quite what it seems. Welcome to the Age of the Uncampaign.

Today’s political system was made for people like Jerry Perenchio, a California-based billionaire with seven figures to burn on a long-shot candidate. Nearly half of CARLY’s funding — $1.56 million, as of late October — comes from him. (Another major donor is Tom Perkins, who as an HP board member voted to fire Fiorina, and famously told an interviewer that in an ideal system, “you pay a million dollars in taxes, you get a million votes” — which is also a pretty good way of explaining super PACs.) Perenchio, the former CEO of Univision and a onetime Hollywood talent scout, produced the dystopian classic Blade Runner, which is set in a futuristic society where real people are indistinguishable from their android “replicants.” CARLY even sounds like a robot’s name.

To the Granite Staters who descend on candidate forums, notebooks in tow, the distinction between campaigns and their replicants can be equally elusive. When Ohio Gov. John Kasich visited an American Legion hall in Goffstown, a few miles outside of Manchester, in October, he was quizzed by a woman he had met at an earlier town hall. At that first meeting, Kasich had told her he didn’t yet have a Social Security plan. But, she told the candidate, when she later got a call from the pro-Kasich super PAC New Day for America, she was told he most certainly did. The reason for the confusion was obvious. The group had his unofficial imprimatur; Kasich recorded a series of TV spots for New Day, which aired in New Hampshire, in which he looks squarely at the camera and explains his positions. Whom, she asked the candidate, should she trust?

Kasich thought about it for a moment. Ignore the super PAC, he told her; they don’t speak for him. As he launched into a critique of a super PAC supporting Jeb Bush, a volunteer was tucking pro-Kasich handbills under the windshield wipers of cars in the parking lot outside, asking supporters to sign up to make phone calls, knock on doors, or donate. Traditional grassroots campaign stuff. But when I took a close look at the flyer on my own car, I realized it wasn’t from the campaign at all. The campaign’s motto is “Kasich for US.” The super PAC replicant on my windshield read “Kasich is for US.” Coordination comes down to what the meaning of “is” is.

Not every outside group is as audacious in its mimicry as New Day or CARLY. But the Uncampaign has upended the system across the board, turning even the most basic of candidacies into something previously unrecognizable. Consider Jeb Bush, the ultimate artifact of the ancien régime. The former Florida governor took his time entering the race last spring. The long wait served a purpose — it allowed Bush and his confidants to assemble a network of outside groups, which he couldn’t legally coordinate with once he was officially a candidate.

In February, four months before Bush announced, his Right to Rise super PAC spawned a spinoff, Right to Rise Policy Solutions, which was formed as a 501(c)(4) nonprofit. It was a clever way around the rules prohibiting candidates from hiring staff until they file papers with the FEC that make their candidacies official. The nonprofit paid a stable of policy advisers for Bush’s campaign-in-waiting before he finally entered the race. In that period, he was free to coordinate and strategize with those advisers, some of whom promptly joined his campaign when he announced. The group’s nonprofit status has the added benefit of shielding its donors from public view.

Mike Murphy, the longtime Bush adviser who launched Right to Rise and its offshoot, recently defended the nonprofit’s creative sidestepping of campaign finance rules. “We think (c)(4)s are totally appropriate,” he told Bloomberg News. “We have one. We’re proud of it.” But in the next breath he slammed a similar nonprofit, Conservative Solutions Project, run by a super PAC supportive of Marco Rubio, as “secret dark money” from “mystery donors,” and fretted that Kasich’s TV spots for New Day were at best an “aggressive interpretation” of the FEC’s coordination rules. So disorienting is the new landscape that even well-paid Republican operatives are starting to talk like Bernie Sanders.

When Murphy and Bush ran into each other in October at a Houston hotel where — in a remarkable coincidence — Right to Rise and the Bush campaign were hosting events at the same time, they paused and, in an acknowledgment of the absurdity of the relationship, embraced in silence.

On a Sunday afternoon a few miles down the road from Kasich’s pamphleteers, Donald Trump’s campaign headquarters was locked up. I found Joshua Whitehouse, the New Hampshire coalitions director, hanging out by the entrance. “Everyone’s out fixing one thing I can’t talk about and another thing I can’t talk about,” he told me, as he took a drag from what he said was not a cigarette.

— Joshua Whitehouse, Trump New Hampshire coalitions director

Whitehouse, dressed in the Granite State uniform of gingham and fleece, looks 15 but he is, like seemingly most people in New Hampshire, one of the 400 members of the state House of Representatives, the third-largest legislative body in the English-speaking world. “We’re gonna continue doing the unconventional stuff that’s working, and the conventional stuff that works — maybe we’ll fold them in too,” he said as I shivered in the cold outside the office park. Staffers are usually coy around people with notebooks. Whitehouse, though, sounded about as unfiltered as his candidate. “All the rules of the playbook are thrown out the window at this point, and that’s what’s driving people crazy. There shouldn’t even be a playbook!”

Trump’s disregard for campaign norms is his campaign, and at the core of that message, more central even than a magnificent wall that Mexico will pay for, is a denunciation of the new campaign finance order. As a rule, conservative candidates haven’t talked much about Citizens United, for the simple reason that they support the ruling and others like it that have kneecapped campaign finance laws. But Trump saw an opportunity. He regales audiences with stories about pathetic candidates flying to Manhattan to beg him for money; when he was attacked by the conservative Club for Growth over the summer, Trump produced a two-year-old letter from the group asking him for $1 million. When his GOP rivals cozy up to the Koch brothers or Sheldon Adelson, he calls them out and his supporters eat it up. In Boston, I even met a Sandernista who told me Trump was his second choice; in wildly divergent ways, both candidates have benefited from the same wave of frustration.

Trump’s unconventional message is backed up by the way he delivers it. Trump does most of his campaigning on Twitter. He conducts TV interviews by telephone. He receives so much airtime on cable news that he put off purchasing his first ads until early November. But there’s a fundamental irony to his unconventionality. Trump might rail against big-pocketed donors, but his campaign is itself premised on using one billionaire’s power and influence to reshape American politics. He just happens to be that billionaire. To that end, Trump didn’t build his own political organization so much as purchase it. Campaigns generally keep down their expenses by relying on volunteers, by hiring staffers who take big pay cuts for a job they believe in, or by racking up huge debt and paying their staffers later. (Nearly five years later, in the case of some of Fiorina’s 2010 California Senate race consultants.) Trump, by contrast, is the best payday many of his staffers have ever seen. Rick Santorum’s campaign spent $30,000 on television ads — total — to win Iowa four years ago; Trump has already paid as much to a driver who once chauffeured Santorum around the state gratis in his pickup. He hired campaign manager Corey Lewandowski away from the Koch brothers-backed Americans for Prosperity by promising him a quarter of a million dollars—nearly 50 percent more than Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign manager earned.

And while his supporters embrace his anti-establishment jeremiads, behind the scenes he was attempting to build the very megadonor-fueled campaign machine he had publicly denounced. The Washington Post reported in October that Trump had appeared at “at least two” events for a super PAC called Make America Great Again — the same slogan that graces his ubiquitous baseball hats. (Make America Great Again shut down a week later.) And before he began denouncing their pernicious influence on the political system, Trump had quietly tried to enlist the support of fellow billionaires, including Adelson and the Kochs. It was only after they turned him down that he sounded the alarm about their political giving. Instead, Trump’s campaign is now fueled by grassroots conservatives, so attracted to a message of sticking it to the moneyed class that they are cutting hundred-dollar checks to a billionaire.

The end product, at least in New Hampshire, is an outfit that looks a lot like a traditional campaign but doesn’t quite act like one. Trump has more paid staff in New Hampshire than any other Republican campaign, and he opened his office over the summer to much fanfare. Trump’s New Hampshire HQ occupies part of the second floor of an office building on the Merrimack River, down the hall from a hospice. But a bland Trump property is still a Trump property. His staff painted TRUMP in big letters on each of the two parking spaces the campaign was allotted; inside, you’re greeted by a huge fish tank and a wall filled with a dozen black-and-white photos of Trump through the ages.

Just like the candidate himself, there was something slightly askew about the whole thing. Considering their boss’ general bombast, Trump’s staffers have a surprisingly low bar for their own success. Joshua Whitehouse told me the campaign wasn’t working hard to win over new voters at this point in the campaign, because “we’ve got 20 percent” of the vote locked up, according to recent polls. He added: “I’m not saying we’re complacent, because we’ll never be complacent.” But 20 percent is not that much. By comparison, in 2012, that would have only been good enough for third place in the state, nearly 20 points behind the winner, Romney. And getting even that kind of showing will be tough without access to the party’s detailed voter file — something every campaign but Trump’s has purchased from the RNC. Whitehouse assured me that volunteer activity is always slow on Sundays — the opposite of what I’d heard from another campaign — and that I should come back on a weeknight. But when I showed up after work on a Monday, Trump’s campaign office was again empty. Then again, he hadn’t trailed in an in-state poll for months. Why bother with the conventional methods of campaign organizing when doing the opposite seemed to be working just fine?

The Lights weren’t on at Ben Carson’s Manchester office either, although the hours posted in the window said they should have been both nights I stopped by. (Sanders’ space above a Citizens Bank was packed with organizers, and even Jeb Bush’s storefront seemed to be buzzing with activity.) More than any other candidate, Trump included, Carson’s rise typifies the eccentricity of the Uncampaign era. Coaxed into the race by a super PAC launched by a pair of conservatives gadflies, Carson tapped Terry Giles, a longtime friend, celebrity lawyer, and former magic-club owner with zero political experience, to hire his campaign team. Not that they stuck around long. A top aide left to work on a farm; another went on safari. Giles quit to help raise money for a super PAC. Naturally, Carson soared in the polls.

The trick is that Carson, like Trump, feeds off the unrest while exploiting it too. Voters who believe the party’s corrupt power brokers have left them behind view him as the antidote. In the process, they have become unknowing participants in a different kind of racket. Carson raised more money than any other Republican candidate in the summer of 2015, almost all of it through paid direct-mail programs. Because only a small fraction of direct-mail recipients donate, it costs a lot of money to make a lot of money — in Carson’s case, he paid $11 million to raise $20 million during the third quarter of 2015. That leaves him with plenty of cash, but it also means that when you donate to Carson, you’re mostly donating to his consultants. This isn’t a new tactic on the conservative fringe, where long-shot candidates or so-called “scam PACs” have used it to separate elderly right-wingers from their money. Carson’s campaign, which did not respond to requests for comment, has just brought it to the fore.

Carson’s embrace of the Uncampaign even left him enough time to write a book, A More Perfect Union — his fifth in three years. A few days after I left New Hampshire, he temporarily suspended his campaign to go on a monthlong promotional swing, for which his publisher provided a book-tour bus. (This could be a potentially illegal corporate contribution, if the FEC decides that Carson was at any point campaigning on the company’s dime. But considering the FEC chairwoman recently filed a complaint against her own agency for incompetence, the possibility of Carson receiving a reprimand seems slim.) At some events, there was a second bus in the parking lot, with Carson’s oversize smile plastered on the side. Supporters lined up to take photos of the vehicle, then met with a crew of volunteers collecting voter information and handing out swag, paid for by a pro-Carson group called the 2016 Committee. Carson might have stopped campaigning, but his super PAC hadn’t. The tour was a resounding success, politically and personally. He even found a few days to take a vacation in Italy with his wife. When a reporter asked Carson about his unusual approach to campaigning, he promised more details in due time. “Maybe I’ll write another book,” he said.

During the townhall in Windham, CARLY volunteers and Carly staffers watched from opposite ends of the gymnasium, as if at a middle-school dance. But after Fiorina had shaken a few hands, smiled for the opposition video trackers, and taken a question from Swedish television, the two sets of staffers converged on the emptying court to coordinate the cleanup. CARLY staffers in red tore down their placards, and together the two groups folded chairs and tables.

A few feet from the entrance to the gym, one of the staffers took a break from stacking seats and huddled with a Fiorina aide.

“When you’re back in DC, let me know,” the aide said.

“We can do drinks,” the staffer replied.

“It’s semi-kosher,” the aide said. One of them joked about coordination, and they laughed and went their separate ways, never to see each other again — until the next afternoon, when they huddled again at a Rotary Club luncheon in Manchester.

The aide was Tom Szold, Fiorina’s national political director. Prior to that, he had held the same job at CARLY — that is, he had built the grassroots organization that he was now not coordinating with. When I asked the CARLY staffer what his role was, he picked up a folding chair and told me he was “just a volunteer.” Perhaps Bob Ellsworth, the super PAC’s chief technology officer, was just being modest.