Attendees listen as President-elect Donald Trump speaks during an event in West Allis, Wisconsin, on Tuesday, Dec. 13, 2016. Trump said publicly on Tuesday that he expected to lose the election to Democrat Hillary Clinton, based on polls showing him behind in several critical states. (Photog by Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Donald Trump is Time magazine’s person of the year, but the most interesting aspect of America’s story this year isn’t the man himself.

Trump has been covered relentlessly. During the 18 months of the campaign and since, cable news has discussed his every tweet. Investigative reporters sifted through all the documents and anecdotes about his personal life and business doings they could dig up. On Election Day, America knew who this guy was, and 62 million voters — a minority but a minority that lived in the right states — delivered him an Electoral College victory.

Some time around 8 or 9 p.m. on Nov. 8, it became clear to the rest of America that Trump had harnessed something far larger than the punditry class and political establishment had imagined. On Nov. 9, residents of blue districts across the country peered outward with some of the same questions that had been asked many times already over the last 18 months but remained inadequately answered: Who had done this? What had the pundits, the prognosticators and Hillary Clinton’s campaign staff all failed to understand? Who are these people?

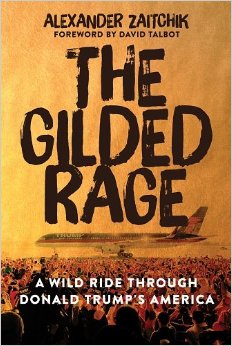

Some answers can be found in The Gilded Rage, a book by freelance journalist Alexander Zaitchik that was released in September and received far less attention than it probably deserved. That last question — “Who are these people?” — is Zaitchik’s jumping-off point for a series of lengthy, fascinating interviews with Trump voters. “Stripped of the condescension, this is a good question,” he writes. “A more difficult, more interesting, and more important one than ‘Who is Donald Trump?'”

Starting in March — the month in which Marco Rubio dropped out and it was starting to look pretty clear that Trump would indeed be the nominee — Zaitchik followed Trump’s campaign around the country. He didn’t cast himself as a reporter; he went into the rallies after standing in the general admission line, or hung around outside of them, speaking with whoever wanted to chat. His interview subjects got to know him as, in his words, “a random Bernie guy with coffee stains on his T-shirts, lots of questions and no media affiliation.”

The results of his effort is a compilation of Studs Terkel-style long-form interviews with voters who defy easy categorization. In Zaitchik’s pages we meet an anti-mountaintop removal activist, an injured veteran who wants universal health care, and a border-state resident whose sympathies lie more with migrants than with the border patrol agents that police the area. They all discuss at length their support for Trump and frustration with the status quo. “Often their cynicism runs deep enough to suspect the whole thing is just another giant setup: they cheer and jeer, their opponents seethe and somewhere out over the horizon, Les Moonves and Joe Scarborough are clinking Arnold Palmers on a private beach in the Hamptons,” Zaitchik writes.

I finished the book three weeks ago, and as Trump has filled his administration with many of the same plutocrats whose business dealings and political lobbying have dealt these voters blow after blow, year after year, there are many passages that I’ve found myself thinking of again and again. One such passage comes in the middle of the book, when an attendee at a Trump rally in central Pennsylvania’s coal country describes the feeling of helplessness that has gripped the area. The good union jobs in coal mining have long since disappeared, victims of America’s natural gas boom and automation; factory work has also dried up as corporations send manufacturing abroad or replace workers with robots. “It’s all gone now. The jobs,” this Trump voter tells Zaitchik. “The smart ones escaped.” For those that are left, there’s “lots of welfare, welfare, welfare.”

He continues:

“There’s lots of Trump support in these towns. They are just tired of everything. I promise you, it’s a 50- or 60-year-old guy who’s seen everything, like us. And he’s, like, ‘We don’t see change. We don’t see it. We tried. We voted Democrat. We voted tea party.’ Nothing’s working. Maybe they were Ross Perot voters, and now, it’s like, ‘Here is our last chance. If we don’t do it now, we’re going to go to our grave and it’s never going to happen.’ That’s what I think is driving this. It is the last chance.”

We spoke with Zaitchik in early December about the book. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

John Light: After having spent the primaries writing this book, how did you feel on the day of the election about Trump’s chances? Did you think he had a better chance of winning than most people on the left and in the media did?

Alexander Zaitchik (Photo by Joseph Gamble Wiley)

Zaitchik: Yes. There was a feeling that I got early on in this project when I started going to Trump events — this hard-to-pin-down feeling that the people at these rallies knew something I didn’t. It took me awhile to get a handle on it, but it grew right up until the last Trump event I went to. That was in western Pennsylvania, just west of Pittsburgh, right in the Ohio-Pennsylvania-West Virginia triangle. The event drew people from those three states. And the energy there and the numbers — the line went around the building six times and it was clear no one was going to get in. People were just celebrating and I was like, “Have you guys seen the polls?” But that was another planet to them, and this planet seemed a lot more real than the numbers being crunched in DC. So yeah, I wasn’t as shocked, I think, as a lot of people were, although I was of course taken aback, the same as everyone, and am still processing.

Light: And that event you’re describing, when was it?

Zaitchik: Two days before the election.

Light: So you were on the trail right up until the end.

Zaitchik: I went back to western Pennsylvania the week before the election and revisited some of the places I had gone to [during the primaries] and went to some last-minute Trump events in the area and yes, there was a huge mismatch between that feeling that was at the air hangar [where the rally was held] and the complacency I saw in the liberal media, absolutely.

Light: Did you have fun reporting the book? Did you enjoy having these conversations?

Zaitchik: Yeah, I mean, “fun” in quotation marks sometimes. But I generally enjoy traveling the US and getting outside of the blue-city enclaves where I spend most of my life. And I like talking to people. I think, ultimately, it’s reporting, it’s my job. I love to do it. And I’ve never really been a pundit or commentariat type.

I especially enjoyed talking to people on this project because things are breaking in such interesting ways. I mean, you had these two insurgencies [during the primaries], and people were thinking about politics in different ways and hearing different things than they’ve heard in a long time. It was an interesting time to travel the country and go to corners that don’t often get a lot of attention. I was in the borderlands, three southern border states. I was in small-town Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and deep coal country. Deep coal country might be the exception — it was getting a lot of attention this year. Everyone was using it as the Rosetta Stone for explaining Trump’s appeal. So I was definitely part of a flood that went down there. But yes, it was a fascinating year to be on the road in America. I did enjoy it.

Light: You say at the end of the book, in the acknowledgements, that you didn’t have press credentials, but folks still opened up to you regardless. I’m curious how you were received. Do you think your approach may have made you more likely to hear a complete narrative than reporters who were just parachuting in and out?

Zaitchik: Yes, the credentials thing does cut both ways. I think a lot of the problems with coverage, and one of the impetuses behind the book, was precisely what you just described, you had these articles saying, “Meet the Trump voter,” and it was someone parachuting into the parking lot of an event with a press tag and sticking a microphone in someone’s face. And it creates this frame where everyone assumes a character and you get the answer you want in a lot of cases.

Not being obvious press and just hanging out and getting to know people as people before — sometimes I wouldn’t even mention that I was working on a project. I’d just be some guy. And then it would come up, and then you built trust. But it takes time. Sometimes people didn’t want to talk to me for hours or days. I’d see them later in the week and be like, “Hey, remember me?” And then two or three beers later they’re like, “Alright, let’s sit down.”

But it’s not something where you can just add water and pop into a scene. It’s the same as reporting any story: The longer you spend someplace, the deeper you’re going to get into something and the more likely you are to get something approximating quote/unquote “the truth” than if you have this artificial divide that’s just the nature of the game if you’re in the press pen and you’ve got your press hat on and you’re this obvious outsider, and you’re asking loaded questions that are obviously geared toward what they’re hearing in the news and they’re already defensive about it. It’s just a recipe for disaster really.

Light: How did you describe what you were doing? Did you say you were writing a book or did you say you were a reporter?

Zaitchik: Yes, I was always completely upfront. I said I was working on an oral history project. A lot of people were quite familiar with Studs Terkel — that was a useful reference point. I just said I was interested in collecting people’s stories, what it’s like to live here, what it was like to grow up here and why you’re so excited about this candidate when maybe you haven’t been excited about anyone in a long time.

I didn’t really try to lead anyone. I didn’t ask about race. It always came up on its own, usually later in a conversation, almost never near the beginning. But I just let people talk and encouraged them to keep talking as much as possible. I have way too much tape, more than I could possibly use. I had to condense the interviews and keep the flow and keep what I thought were the salient points, biographical and otherwise.

But yes — once people started talking, they were thrilled to have someone who really wanted to get into the guts of their lived experience and the nuances of how they saw things. And often there was a level of self-awareness and critical thought involved that you wouldn’t think necessarily was the case. A lot of these people saw the same things in Donald Trump that I did and other critics of Trump did but were nonetheless willing to roll the dice for whatever reason, and they all had their own slightly different reasons.

Light: I read somewhere that you spoke to over 100 people for this. How did you decide who you were ultimately going to include in the book?

Zaitchik: That’s a good question. There were certain themes that re-emerged again and again. I didn’t do 100 long-form interviews, but for whatever number of months it was, I basically only spoke to Trump supporters. Some of those were long conversations, some were short. But I took the themes that kept recurring and just chose people that seemed to embody those themes in the best way and were the most articulate and seemed to be the best representative of those themes. But I tried to get the ones in there that I heard the most often.

Light: A lot of campaign coverage this year seemed somewhat reductive — 800 words where at the end we arrive at a point, the author’s making an argument. What advice would you give for how journalists should be approaching political coverage next time around?

Zaitchik: Well that’s a tough one. It’s not true that everyone was just up in some cubicle in Washington or Manhattan writing punditry. I mean, maybe the Vox guys or something are an extreme. But there was a national press corps that was traveling widely and meeting people and writing about this stuff. So I don’t feel comfortable saying nobody was out there trying to figure out what the real story was.

But yes, for whatever reason — and this is where you can maybe get into the politics of the press — there was this really strong, almost instinctive urge to make it this false binary. It was just so obviously counterproductive, but they kept insisting that it was this or that, the economic versus the racial motivation. And it was just baffling to me. The only way to make sense of it is that it masked some desire to let the Democrats off the hook — I didn’t know how else to make sense of it.

But clearly it was a false dichotomy, and I think we all understand that at some level — and I think people are starting to finally come around that. I know Van Jones is supposed to have some special where he gets into the interplay between the two. A lot of writers have started to talk about how one can influence the other, and there’s history here to think about and it’s a huge thing that we’re going to have to work through. But obviously it’s not as simple as this or that.

For that reason, this was a maddening book to try to do press because I was in these little tiny windows, I was expected to say economic or racial and I was like, “What is this, a game show?” It always made me look bad; there was just really no way around it. You know, people just force you to come down on one side because there’s 15 seconds before the commercial break. You don’t want to do that but you also aren’t allowed to sit there and not say anything. So, if I had to come down on one side I would say — and to this day defend — that the economic and the social are first and second and maybe even first, second and third motivations, before you start getting into the racial ethno-national stuff that everyone wanted to put up first.

And I say that because it’s my reporting and that’s all I have. I’m sorry, but I’m not going to listen to some guy crunching numbers over my own experience. I just did a random sampling of Trump supporters in six states. It’s not definitive. It wasn’t some monumental study. But I got to know a lot of people and I gave them a lot of time to reveal themselves and I think I’m a pretty decent judge of character. I’ve got 20 years of covering conservatives and far-right politics. I’ve covered professional racists, casual racists — I’m not naïve about what racism is and how it manifests. So, that said, what [Trump supporters] wanted to talk about again and again and again was the industries that they grew up with that are gone. And the nephews who are on heroin. And the service industry jobs that suck. And how these people aren’t going to have pensions. And it’s not fair. And, “This guy’s the only guy who’s pissed about it and whose anger I can relate to. And he’s not a perfect candidate or a perfect man but maybe he’ll be like an FDR-type class traitor and he’ll think about the little guy,” as the miner in Pennsylvania told me.

And yes, racial stuff would come up, the anti–PC stuff which you can unpack and try to figure out what’s going on there. Some of these guys had more than a little Bubba in them, no doubt. But it’s not like a race-hate movement. It just wasn’t. Most of the guys I talked to — and I focused on lower-income guys of a certain age, so it was somewhat self-selecting in that way, I wasn’t going into upper-income homes or country clubs, but — these guys weren’t on Twitter. They had no clue who [“alt-right” icon and white nationalist] Richard Spencer was. You mention these Twitter storms and stories that got a lot of press to these guys and they just look at you like you have three heads. You know what I mean? Sometimes on the coasts, people who are really heavily involved in media and social media just get this really distorted view of what’s driving these Rust Belt votes. The younger you get, the more that stuff is visible, but, you know, when you get above like age 35 — I mean, I just didn’t encounter it once.

Light: You mean they weren’t plugged into all of the various online communities that were supposedly playing a role in the election.

Zaitchik: Yes, and what’s being called the “alt-right:” organized racist and anti-Semitic activism.

Light: We’ve been hearing a lot about fake news and the role that conspiracy theories and sites like Alex Jones’ Infowars played in the election. Did you encounter a lot of that? Because there wasn’t much of it in the book.

Zaitchik: You know, I think — and I hate using this term but I guess it has its uses — the “average” Trump voter is a mix of Howard Stern and Rush Limbaugh, with dominant side of Howard Stern.

Light: In terms of personality or media consumption?

Zaitchik: Just in media consumption, personal values. One of the things that really came home in doing this project was this conservative voter that we have in our mind is sometimes an anachronism. We think of people who grew up in some black-and-white Leave It to Beaver America, but even these older guys who are near retirement age have been listening to Howard Stern for like 25 years. Some of the characters in the book say that while they were in college they were doing meth, or they grew up smoking weed and dropping acid. These are conservative voters now.

And so, yes, I encountered a lot of conservative media consumption that was not what you might consider wholesome. It wasn’t just straight AM talk radio, and Alex Jones is, yes, increasingly in the mix. When I was at the RNC I went to some events where it was all his people and he, of course, brought a lot of people into the Trump campaign and vice versa. So, that’s an interesting relationship. I didn’t really focus on it but I would not say Infowars came up in a single conversation I had.

Light: You talk a lot about the protests in the book, and how there were a lot of the Trump voters you were speaking to who felt like the protests didn’t serve a purpose beyond polarizing the community further. That was their perspective. How did you feel about the protests? Did you feel that they were effective in some way or did you agree with the Trump voters, that these protests were just making people angrier to no productive end?

Zaitchik: That was a tough one for me, because my background and my sympathies were with the protesters and the groups that were protesting. At the same time, I was on the other side going into these rallies with people I’d come to know, and I was going through these security lines having invective hurled at me, sometimes physical objects, and, you know, I did see it from the other side, too. Man, some of these things were just vicious.

Like in Albuquerque — I tried to do it justice in the intro to that chapter — they basically crashed the gate. They crashed the security lines and starting burning Trump merch. I mean, it was crazy. I can’t believe there weren’t more violent clashes outside in the streets. So I’m not sure what they accomplished. Obviously, I think protest is important but some of them veered into just interfering with people’s right to assembly and First Amendment rights. I don’t like to see that.

Light: A lot of folks that you spoke with claimed to want policies that overlapped to some extent with Clinton but were also very much in line with the things that Bernie Sanders was talking a lot about during the primaries. Did you encounter much confusion among these voters about whether they should support Trump or support Sanders?

Zaitchik: Yes, that was one of the things that also made me want to probe Trump fans a little bit: exploring that overlap and finding out if there even was one. A lot of people did indeed perk their ears up when they heard Bernie Sanders speak. A lot of people liked a lot of what they heard and might have been tempted by a candidate that was not a self-described socialist from Vermont.

Light: Interesting.

Zaitchik: You’ve got to understand that that word for these people who are still, for a lot of them, coming out of conservative communities, conservative backgrounds, they grew up in the Cold War — that’s a big river to cross. They still have all this conservative propaganda pounded into them about how there’s nothing that’s free and socialism is evil and godless. And there’s this cognitive dissonance because they’re also starting to think very critically about capitalism and the products of the 2008 crisis and they’re struggling to get to some new place. Trump tapped into that with his poisonous right-wing populism. But he was tugging at them in one way, and Bernie was tugging on a different string, and there was some confusion. I tried to probe that as much as possible but often it came down to language. It was fascinating to watch people be like, “But he’s a socialist. I can’t vote for a socialist. But of course I want these things.”

It made me think that if we have people who maybe aren’t using certain words we might get a little bit farther. For example, in Wisconsin there was a guy who blushed and was ashamed when he explained to me what BadgerCare was because he was raving about his BadgerCare. And he was like, “Well, it’s Medicaid, but it’s BadgerCare. It’s really BadgerCare.”

So language is so key, I think, in talking to a lot of these people and getting that space opened up further and in bringing some of them in. But there is a lot to work with there. I’m encouraged by the way a lot of people are open to — you know, not too long ago they were still mimicking the small government, the old Republican verities — but Trump represented a break for a lot of them in some ways even if they don’t quite understand it. Even if Trump doesn’t quite understand it. I mean, they were cheering his calls for defending Medicare and Social Security, which was a huge part of his stump speech. It was in every single one of them. And it got cheers as big as anything — maybe not the wall, but he said it everywhere he went. And that was a pretty big break from what everyone else [in the Republican primary] was saying. He was talking about the little guy and using some very FDR rhetoric, which the voters are about to be very disappointed in, I think. But that rhetoric is what they were responding to, and it has brought them to a new place and now I think a good number of them might be up for grabs, especially after the betrayal they’re about to experience.

Light: Right. I think more than one voice that you had in the book said that they’d tried being Democrats, they’d tried being Republicans, they tried being tea partiers — none of it worked. And now they’re going to try this Trump thing. It sounds like you’re saying that you don’t think they’re going to feel any better about this vote in the long run than they felt about any of those others.

Zaitchik: It would be pretty shocking based on the way the administration is shaping up.

Light: Have you heard from anyone that you met — folks in the book or otherwise, any of the Trump supporters that you were in touch with on the trail?

Zaitchik: I had spoken to a couple shortly before the election, not since the election. I’ve been running around. But one of my plans is to get back in touch with people in the new year and see where people are at.

Light: So you’re intending to follow up on some of this in the months ahead?

Zaitchik: Yeah, I plan to. I’m not sure in what form. What’s happening now is kind of — stakes are high. One thing you notice talking to people is just that sort of basic political consciousness among the working class is in such a degraded state. These are things that people used to understand because there were unions to give people a framework. Now unions aren’t what they were, and people have been subjected to 40 years of counterattack propaganda and they don’t know who the enemy is. They don’t quite know how to articulate that.