This Bill Moyers interview provides a behind-the-scenes look at the life and works of the mastermind behind All in the Family, The Jeffersons, and One Day at a Time. Producer Norman Lear discusses idea generation, writing, working with actors and playing the game to succeed in the world of television. This program includes interviews with collaborators Carroll O’Connor, Bonnie Franklin, Marla Gibbs, and others, as well as recollections from Lear himself and his wife.

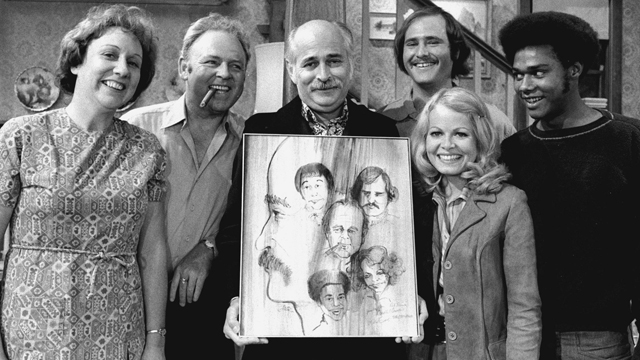

“Norman Lear (center) created, developed and produced the hit show All in the Family, which ran from 1971 to 1979. The politically charged sitcom starred Jean Stapleton, Carroll O’Connor, Rob Reiner, Sally Struthers and Mike Evans.

CBS /LANDOV”

TRANSCRIPT

BILL MOYERS: I’m Bill Moyers. So far on this journey, we’ve seen that to be creative, you have to take risks, question what other people take for granted, look at the familiar in a brand new way, seize luck as it passes, use your imagination, and allow your unconscious to use you. Norman Lear does those things, and that’s why he’s one of television’s top creators. Here’s what Norman Lear says about why television is not more creative today.

NORMAN LEAR: The three networks depend on ratings only. The name of the game for three networks is how do I win Tuesday night at 8 o’clock. And so long as that is what the name of the game is, and that’s what motivates them to decide on a show, they will decide on what they think will work, what they think will beat the opposition, and not what they think is good and will beat, consequently, the opposition.

If you’re caught up in numbers and winning or losing and how do I beat NBC and ABC, if you’re CBS, at 8 o’clock Tuesday night, then you will say, well, wait a second, what’s working. Animal House is working– let’s try. Go to MTM or go to TAT or go to Lorimar and ask them if they’ll turn out an Animal House.

Give them the pattern or give them the cookie cutter and ask them if they’ll cut this cookie for us. Very little chance for creativity in that. I’m not suggesting, for a second– I’m a commercial fellow– I have never done anything that I didn’t wish to communicate to everybody. I’m not a poet. Poets do not mind talking to narrow audiences, and thank God for them.

But I just happen to be somebody who wishes to communicate with the broadest amount of people, the most people. And I’ve not lost sight of that. And I understand that networks want to succeed. They want their stockholders to profit better than stockholders of the other two networks. But one can go about that, a network can go about that differently. You can go about that the way we just talked about.

This is working here. Take that cookie cutter, make another cookie. Or you can say to people, come to work every day. Listen to your families, watch your children, read your newspapers, exercise your vital abilities in the course of producing and directing and writing and performing for CBS– if it happens to be CBS– and we’re going to take your product.

And because it represents your best, and we think you are the best– that’s why you’re working here– we will go with that. I don’t see what anything mutually exclusive about being commercial and achieving excellence.

BILL MOYERS: Norman Lear’s impact on television in the ’70s proved that popularity and quality are not mutually exclusive. Last week we looked at the creative process by which he had gathered around him men and women of talent and inspired them to create. This week we look at what inspired Norman Lear’s own creativity.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BILL MOYERS: Norman Lear took on issues television had ignored and turned them inside out like a jacket until he found the humor that lines them. Good Times and The Jeffersons were the first series about black families. Maude was the first devoted to an independent woman who spoke her own mind. One Day at a Time became an honest portrayal of a mature, single parent.

And All in the Family was about a man who couldn’t stop the world from changing. He could only fume at it. When it appeared, All in the Family was denounced by some conservative critics as a diatribe against the working class and by some liberal ones as an apology for bigotry and reaction.

Lear was excoriated for turning racism and discrimination into one-liners and for even mentioning sex at all. But millions started laughing and kept on laughing because, well, the shows were funny. They were about life, too. And we got so involved with the characters that every week’s visit was like a family reunion, black sheep and all.

The writing and acting were superb, aided and abetted by Norman Lear’s ability to draw from life, itself, what we would see on the screen. And that was no accident, because for Norman Lear, experience is the writer’s notebook.

NORMAN LEAR: I think it’s just a question of pulling the strands of life that one has experienced– one has listened — the sights and sounds of a lifetime, and just having them available for use. The unconscious is a terrific partner, always silent — just there with answers, slipping you pieces of paper, whispering in your ear.

You go to bed with your unconscious every night. And I don’t know how many– I would imagine everyone alive has had the experience of going to bed with a problem and waking up with the answer, whatever the problem might be. And it is comforting, if one remembers to think about it, that one has a partner in one’s unconscious that’s working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and will forever be there.

BILL MOYERS: Ideas started dropping into Norman Lear’s unconscious like letters dropping into a mailbox when he was just a kid. His father was a salesman, often down on his luck, and Lear had to scrape, improvise, and make his own breaks.

NORMAN LEAR: I am never touched more by anything in life than I am by the sadness of a man who’s having difficulty supporting a family, and we did a lot on All in the Family, where Archie was facing that difficulty, constantly, because I watched so much of that with my father and his brothers during the Depression.

I was a kid of the Depression. And there wasn’t anybody on either side of my father’s family who, really, made it, who, really, was a good provider, which was the expression.

BILL MOYERS: Yet you, yourself, had some difficult moments. You lost a job in 1942, I think, or ’45, somewhere in there. You lost a job. You came to Hollywood. I don’t think many people realize this– started a company to produce a novelty ashtray. That went under.

[LAUGHTER]

NORMAN LEAR: I forgot about that.

BILL MOYERS: That went under.

NORMAN LEAR: I invented something– talk about creativity. Somebody once said that man is made to be creative, from the poet to the potter. Man is made– I believe that. I believe everybody has a touch of that. I invented and secured a design patent on something called the demi-tray, as useless an item as one can imagine.

It was a little ashtray that clipped onto a coffee saucer this way. It was this big. And it had two– you could put a cigarette this way, and it clipped on, here. Had an exciting Christmas season, selling a great deal of these, and took the money and put them into tools that we had made and put them into tools and dyes for the next Christmas to make a series of other important items– candle snuffers– little, silent, butler ashtrays. But I didn’t know anything about retailing, and we lost everything that we had made out of the original demi-tray. And two months later, I started to sell baby pictures.

BILL MOYERS: Baby pictures? That you took yourself?

NORMAN LEAR: Somebody else took the pictures. I made the appointment for the photographer. The photographer took the pictures, and then I would go back and sell the proofs, and did poorly, very poorly.

BILL MOYERS:What happened after that? When did you get your first break in the business?

NORMAN LEAR: Not long after I was here. We were living in one little room behind– a little, one-room cottage behind another home in Hollywood. And I’d met a fellow by the name of Ed Simmons, who was married to a cousin of mine. And he wanted to be a writer. And our wives went to a movie one evening. We were babysitting, and we wrote some material together.

He was going to write it, so I helped him. We, laughingly, had a wonderful time writing it. They came home, and we went out and sold it. We sold this parody that we had written for $25, but it was $25– like that– and for having fun, for having a good, good, time laughing and working.

And then we decided we would continue writing, asked the wives to go to the movies often.

[LAUGHTER]

And every evening we wrote, and every evening we went out. And three out of four times, we sold, for $40, $50, something.

BILL MOYERS: Is it true that you told Danny Thomas’ agent that you were a reporter for The New York Times?

NORMAN LEAR: I called the Agent, first. And I said, quickly, “my name is Mo Robinson. I’m at the Los Angeles airport. I’ve been out here for two days interviewing Danny Thomas. I have two last-minute questions– whoops, my plane, they’re calling my plane–” and they gave me a phone number, quickly.

So I called Thomas, and he happened to pick up the phone, because he was alone in the house. Anyway, he enjoyed the idea of how we had reached him, and he asked me if I had anything now. And I said, oh, yes. He said, well, where are you. I said, Hollywood. He said, come on over. And I said, well, it’s going to take about 2 1/2 hours.

And he said, but you said you were in Hollywood. I said, yeah, but I’ve got other things to do. “You’ve got something more important to do than sell me a piece of material, kid? I never heard your name before.” Well you see, we hadn’t written it yet.

[LAUGHTER]

NORMAN LEAR: So it was just an idea. He would wait ’til 7 o’clock, and wrote it, raced out there. And he paid $500 for it, did it two nights later. And four nights later, we were back in New York writing the Jack Haley Ford Star Revue, an hour television show every week.

BILL MOYERS: It was in the 1960s that Norman Lear saw a BBC program, titled Till Death Do Us Part. He bought the adaptation and wrote a script for a pilot, which he called Those Were the Days. By the third pilot, it was All in the Family. And there was more truth in the title than any of us knew.

NORMAN LEAR: I never knew anybody who had more joy in life than my father. And my father was an amazing character, not, in some respects, unlike Archie Bunker.

[EXCERPT FROM ALL IN THE FAMILY]

ARCHIE BUNKER: My old man, let me tell you about him– he was never wrong about nothing.

MIKE: Yes he was, Arch.

ARCHIE BUNKER: [SLURRING] Ah– father who made you, you’re warm, your father, the breadwinner of the house, there, the man who goes out and busts his butt to keep a roof over your head, clothes on your back– you call your father wrong. Ay, ay, your father– Let me tell you something, you’re supposed to love your father, because your father loves you. And how can any man that loves you tell you anything that’s wrong. Oh, what’s the use in talking to you.

NORMAN LEAR: And he was the man, literally, who would say to my mother, “Jeanette, stifle yourself!” I always wanted Carroll to do it that way– to take her like this– “Sti-fle!” Things would kind of– never hurt her, but he would scream, “Stifle, Jeanette!”

One grows in a climate. I grew in a very active, passionate family, and I listened. I don’t know what made me the kind of listener. Maybe it’s because as a kid, I never had a chance to get a word in anyway, and so I learned to listen and through listening, learned to observe.

Somebody once said– I think it was my good friend, Herb Gardner, who described people as living at the top of their lungs and the edge of their nerves. My family lived that way.

BILL MOYERS: So when Edith and Archie were arguing, often those were your parents arguing.

NORMAN LEAR: Oh yeah, as a matter of fact in a film, Divorce American Style, a lot of years ago, there was a shot of Dick Van Dyke and Debbie Reynolds arguing– they were the parents in the kitchen– and the camera, as they were in this very passionate argument– the camera panned up to a transom, and then dissolved through to another transom on the second floor, and panned down.

There’s a little boy in bed, 11, 12 years old, and he was scoring the argument. Mother on this side, father on this side– he was giving them points for how they broke dishes or how they won one point or the other, and the kinds of articulation. He was giving them points for everything. And that was me. My father had an enormous effect on me and his brothers, my uncles. My father was a grandstand player. I mean, he loved all the time, but he didn’t have the time to show it all the time. But he had these wonderful grandstand moments where he would show it. Like, he didn’t love enough when, for my 17th birthday he told me I could use his car, a Hudson Terraplane, to take my best girl to the Westport Theater.

NORMAN LEAR: My father was to be home at 5 o’clock or so to give me his car. I had a car that was a 1932 Ford something. And 5:00 arrived and 5:10 and 5:15 and 5:30, and my father wasn’t there. And finally, at 10 minutes to six or something, with the tears pouring down my face, I got into my little Ford, and I chugged along to West Hartford, and I picked up Adrian.

And I get on the Merritt Parkway, having gone all the way through all those little towns on the Merritt Parkway within 15 minutes of Westport, and I hear “honk, honk, honk.” And my father– I’m forced over to the side, and there’s my father. He had chased me all the way, found me. I got into his Terraplane. He took my car, and we had the car for the evening.

Now that was the great grandstand moment. I had forgotten it. I had totally forgotten it. But I was lying in therapy on somebody’s couch a great many years later, and in the telling of that story, I just fell to pieces. And never, ever forgot, again, for not an instant, how very much I loved him.

[EXCERPT, MAUDE]

MAUDE:And just as my date and I were walking up the high school steps, there was my father. He was out of breath and sweating, and he was holding this coat with the Persian lamb collar. He had gone to the furrier’s home and pleaded with him to open the store, so that he could buy that coat. And then he broke every traffic law in the books so that he could get there in time to give me this coat with the Persian lamb collar so that I could wear it to the prom. Oh, how could I have forgotten a thing like that? I mean, what a sweet, thoughtful, loving thing to do. You know, I think, deep down– I never said this to anyone, not even to myself, but I think deep down I loved my father. Oh, how I loved him.

BONNIE FRANKLIN (Anne of “One Day at a Time”): Norman used a lot of himself in everything that he did. And that, I think, legitimized the work that was being done, here. And his characters are, usually, based upon his family, people he loves, his friends, and he manages to take everything that he thinks about this character, I think– all of his experiences and all of this hopes, really– and he puts it into a person who can talk and make other people laugh.

NORMAN LEAR: I have found no two days, raising three daughters, married to the woman to whom I’m married, the same. No two days are ever the same. And so it seems to me, in family life, there is no way of running out of stories.

FRANCES LEAR: Although many people think that I am Maude, I am not Maude. Bea Arthur is Maude. And because she and I are both tall and dark and strong and Jewish, many people think that we’re alike. And in some respects, Norman has taken episodes of my life and put them into episodes on the screen for Maude.

[EXCERPT, MAUDE]

Uh, it’s me, all right. I’d recognize that face anywhere– the innocent glow of Donna Reed — and the crisp features of George C. Scott.

NORMAN LEAR: To hear people openly discuss the things we all feel is to unite and comfort all of us, because I believe we all feel, basically, the same things.

[EXCERPT, THE JEFFERSONS]

GEORGE: Come on now, Louise, this is crazy. What are we fighting about? We got a great marriage.

LOUISE: I’m not so sure anymore. The Willis’ were right. Our marriage does need improvement.

GEORGE: No it don’t! We’re happy, you hear! Happy, happy, happy! I’m happy, see! Hahahaha. You’re happy. You have always been happy. You’re going to keep on being happy, even if it kills you.

LOUISE:Where are you going?

GEORGE: Down to Charlie’s Bar to celebrate how happy I am. Hahaha.

NORMAN LEAR: Whatever interpersonal problems this couple faces, we know everybody can relate to out there. And the more crucial the problem, whether it’s in society or in the interpersonal relationship, the more the audience is with it. And when you ask them to laugh or spark them to laugh, they laugh harder.

[EXCERPT, THE JEFFERSONS]

GEORGE: Valentine’s Day!

LOUISE: Every year since we’ve been married, you’ve given me a box of chocolates, but this year– nothing.

GEORGE: Look Weesy, I didn’t forget. I was just thinking of you.

[LAUGHTER]

LOUISE: What?

GEORGE: Well, you are getting kind of heavy around the hips, there, you know.

LOUISE: Oh, so now I don’t look so good to you.

GEORGE: Nonono, you look great to me– bigger and better than ever.

[LAUGHTER]

NORMAN LEAR: For me, it’s all a celebration of life. There never was a doubt in my mind that Archie Bunker and Edith were going to go into the next day and the next week, the next month and the next year, together. Nothing was going to stop that. Or the Findlays, Maude and Walter, or the Jeffersons, they were not going to separate. They were always going to go into the future together. So those were not reconciliations. Those with the ends of moments of conflict or moments of passion waiting for the next moment to arrive, and certain that the next moment would arrive.

[EXCERPT, ALL IN THE FAMILY]

ARCHIE BUNKER: We’ll just go sleepy-bye, huh?

EDITH BUNKER But remember, whatever happens, I love you.

ARCHIE BUNKER: I love you, Edith.

EDITH BUNKER Truly.

ARCHIE BUNKER: Thank you, thank you.

EDITH BUNKER [SINGING] I love you tru-ly, tru-ly dear. Life with it’s sor-row, life with its tear, fades into dreams when I feel you near–

[APPLAUSE]

EDITH BUNKER [SINGING] For I love you tru-ly, tru-ly dear.

ARCHIE BUNKER: Edith, come on, darling, listen. I know your singing, and you know you’re singing, but the neighbors are liable to think I’m torturing you.

[LAUGHTER]

NORMAN LEAR: I think the shows love people and love the human condition, and that’s why they deal so– they try to, anyway– they try to deal so deeply in the human condition. They wish to go, vertically, into the human condition and not just skip along the surface.

[EXCERPT, ALL IN THE FAMILY]

ARCHIE BUNKER: Uh, Edith, uh– I’ll tell you the truth, Edith, I ain’t myself. What I mean is let’s not start something that I can’t finish.

NORMAN LEAR: The things people care about the most are the things they laugh hardest at. And laughter and tears run hand-in-hand. And it’s kind of nice to get people– if they’re laughing hard enough, perhaps– to try to move them to tears, but with a basic premise that people will laugh harder if they’re caring.

[EXCERPT, ALL IN THE FAMILY]

EDITH BUNKER I’m sorry, I thought I was doing a good thing.

ARCHIE BUNKER: Oh sure, a good thing. That’s you all over– always doing good. Edith the Good– you never get mad at nobody. You never holler at nobody, you never swear, no nuthin. You’re like a saint, Edith. You think it’s fun living with a saint? It ain’t. It ain’t, at all. Look at this. You don’t even cheat to win. You cheat to lose. I mean, Edith, you ain’t human.

EDITH BUNKER: That’s a terrible thing to say. I’m just as human as you are.

ARCHIE BUNKER:Prove you’re just as human as me. Do something rotten.

STRONG>EDITH BUNKER: All right, I will. You’re a– you’re a– Ooh! I can’t.

ARCHIE BUNKER:I know you can’t. You can’t do nuthin that ain’t good. You’re right, you ain’t human.

EDITH BUNKER: I am so human!

NORMAN LEAR: I think a good clown can make you scream with laughter and cry with despair, and do them, almost, immediately adjacent. I mean, a great clown can make you laugh and then just by a change of expression, bring you to tears.

BONNIE FRANKLIN:That’s one of the toughest things, I think, he ever did. And I became aware of it on All in the Family, which is taking an issue that is, normally, just something that you would get in screaming tears over and somehow make it work as a comedy thread. I remember a show on All in the Family about Edith having breast cancer.

[EXCERPT, ALL IN THE FAMILY]

EDITH BUNKER: I’m afraid if I have this operation, Archie won’t think of me in the same way.

IRENE: Oh Edith, stop scaring yourself. Archie loves you, and nothing’s going to change that.

EDITH BUNKER: But I’m going to change a lot.

IRENE: Listen, even if you have to have the operation, it’s still going to be all right. Believe me.

EDITH BUNKER: You don’t know.

IRENE: That’s just the point, Edith, I do know. I know.

EDITH BUNKER: You mean– you?

IRENE: Six years ago, and you see how Frank and I get along. It hasn’t made one bit of difference in our marriage. Don’t bother looking, Edith.

EDITH BUNKER: I wasn’t.

NORMAN LEAR: The audience laughed, but laughed with such warmth and identity. It didn’t resent laughing in the middle of that situation, because it was an absolutely humorous moment in the middle of a really serious situation.

EDITH BUNKER: Oh, Irene, you made me feel so much better.

IRENE: Aww.

[APPLAUSE]

NORMAN LEAR: It seems to me, Bill, I have never been in a situation in my life, however tragic, where I didn’t see some comedy. And it may be just growing up the way I grew up. But I don’t think that one’s serious observation of life is lost in seeing it through that end of the telescope that finds what’s funny in it. I think, somehow, it’s even sharper.

So it may be that the clown is just born understanding, not the closeness, but the oneness of laughter and tears. I can think of moments with Carroll and Bea, where I have laughed so hard– the tears pouring down my face– I think they will tell you that I may be the most insane laughter they have known. I mean, I am. And I had known, as I was laughing, that these people were adding time to my life, that that laughter had to be adding time to my life.

This transcript was entered on July 15, 2015.