The recent DC circuit court decision that killed net neutrality put the Federal Communications Commission — and its newly appointed head, Tom Wheeler — in the position of needing to figure out what they can do to maintain their authority to ensure an open Internet. If they don’t, the Web as we know it could dramatically change. Journalists and advocates point to a future in which Internet service providers (ISPs) could give users faster access to some sites and slower access to others. So if, for example, Hulu paid Comcast to allow viewers a faster connection, and competitors such as Netflix did not, Comcast subscribers might decide Netflix, with its slower streaming services, was not worth their money.

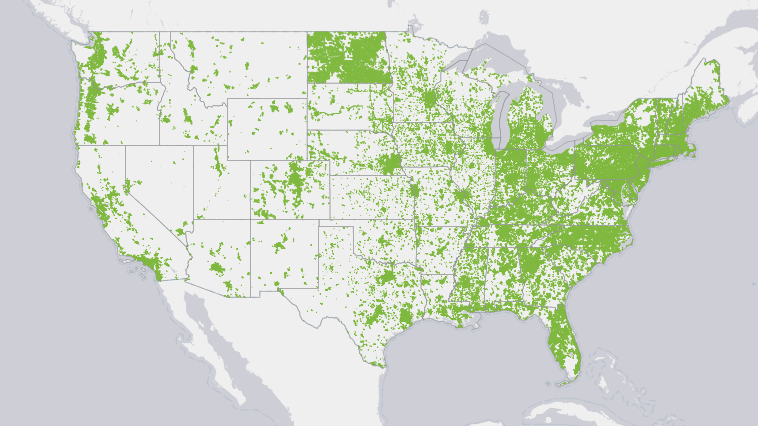

In another scenario — one that could create more serious problems for our democracy than slower video streaming — ISPs could grant users faster access to, say, The Wall Street Journal than to The New York Times. They could choose to block other sites altogether. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that, in many parts of the US, ISPs have monopolies. (The map below highlights in green areas where consumers have at least two options for broadband providers. Clearly, consumers in many areas don’t.)

The FCC and President Obama have both indicated that they don’t wish to see such a dystopian vision become reality. “I have been a strong supporter of net neutrality. The new commissioner of the FCC, Tom Wheeler, whom I appointed, I know is a strong supporter of net neutrality,” the president said in a recent video chat.

There are a number of options for how to move forward.

The Washington Post’s Brian Fung reported that Wheeler is leaning towards taking enforcement actions against ISPs that use their monopoly power to actually make the kind of discriminatory decisions outlined above. “We are not reticent to say, ‘Excuse me, that’s anti-competitive. Excuse me, that’s self-dealing. Excuse me, this is consumer abuse,'” Wheeler said. “I’m not smart enough to know what comes next [in innovation]. But I do think we are capable of saying, ‘That’s not right.’ And there’s no hesitation to do that.”

And there’s another, broader option. The DC circuit court supported the idea of net neutrality in principal, but said that the FCC was enforcing it incorrectly. The commission categorizes ISPs as information services, not communications services, and the FCC has a lot more power over the latter. If ISPs were considered communication services, FCC-imposed rules mandating net neutrality would be legal. So, instead of taking action after broadband monopolies do something the FCC finds problematic — as Wheeler proposes — the FCC could prevent those problems from arising in the first place by reclassifying the Internet as a communications service.

Last week, the nonprofit advocacy group Free Press, in cooperation with 80 other organizations, delivered petitions with more than a million signatures to the FCC, urging reclassification. And yesterday, House and Senate Democrats introduced a bill that would reinstate net neutrality rules as they stood before the DC circuit court decision and keep them in place until the FCC has come up with new rules.

But Republicans have warned that reclassification would create substantial pushback from ISPs and their lobbyists, as well as investors on Wall Street.

In an interview with Bill Moyers last year, Susan Crawford, a law professor and former assistant to the president for science, technology and innovation, said that thinking of ISPs as a communications utility, like a phone company, could have a number of benefits, including making Internet access more democratic.

“They’re in the business right now of finding rich neighborhoods and harvesting, just making more and more money from the same number of people,” she said. “They’re doing really well at that. Comcast is now a $100 billion company. They’re bigger than McDonald’s, they’re bigger than Home Depot. But they’re not providing this deep social need of connection that every other country is taking seriously.”

Watch a clip from the interview: