In June, President Obama announced his Climate Change Action Plan, which calls for cutting total U.S. carbon pollution by 17 percent from 2005 levels by 2020. A key part of that effort is placing limits on the amount of CO2 emitted by power plants, and the EPA plans to do it by enforcing regulations under section 111d of the Clean Air Act. The little-known section of the 1970 law allows the EPA to develop and apply regulations to specific types of polluters — e.g., sulfuric acid manufacturers, landfills and, now, power plants.

The EPA explains:

For newly built power plants, the plan calls for EPA to issue a new proposal by September, 20, 2013, and to issue a final rule in a timely fashion after considering all public comments, as appropriate. For existing plants, the plan calls for EPA to issue proposed carbon pollution standards, regulations, or guidelines, as appropriate, for modified and existing power plants by no later than June 1, 2014 and issue final standards, regulations, or guidelines, as appropriate, by no later than June 1, 2015.

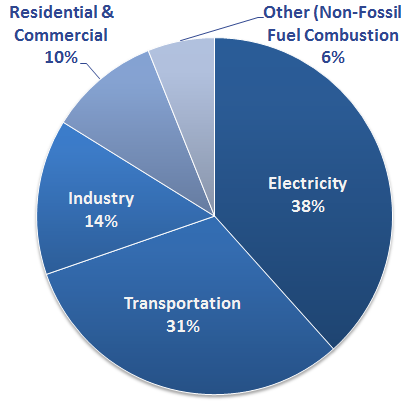

Approximately 40 percent of America’s carbon footprint comes from power plants (transportation is the other big one), and there are many viable alternatives to the dirty fuels many plants burn. That’s why environmental groups like the Natural Resources Defense Council argue that targeting power plants makes sense: Power plants don’t have to get 37 percent of their energy from coal, and an additional 30 percent from (somewhat cleaner, but justifiably controversial) natural gas. Far more than the current 12 percent could come from renewable sources.

Before any new law or policy can go into effect, there is an extensive rulemaking process. With a situation as complex — and contentious — as regulating already-existing power plants, that process can take years to complete.

This week, the EPA will engage policymakers and community leaders in that process with a “webinar” video explaining the Clean Air Act’s section 111d and how the agency plans to use it.

Of course, the industry that stands to lose the most — the industry responsible for extracting and burning America’s most widely used dirty fuel, coal — isn’t taking this lying down. The Center for Public Integrity (CPI) reports that the new regulations could “halt construction of future coal plants” and mean potential closure for many of the more than 500 coal plans operating today. They outlined three ways in which the industry will likely push back.

- Industry is sure to flex its muscles in the regulatory process, inundating the EPA with comments, analyses, legal opinions and technical documents, and picking apart its draft plans.

- Plan critics will engage lobbyists to influence the rules’ language, enlisting support from other federal agencies, and offering alternatives to the White House.

- And, the coal industry is sure to oppose strict rules in a scorched-earth strategy infused with aid from allies in Congress.

This sort of multipronged approach by industry to weaken yet-to-be-written regulation is a time-honored tradition in Washington. A recent corporate interest group success story can be seen with the painfully slow implementation of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, the law written to reign in the risky banking behaviors that led to the 2007-2008 financial crisis and caused our ongoing international economic woes today.

Three years after the president signed Dodd-Frank into law, regulators are besieged by comments on the rulemaking process from Wall Street, and politicians have been inundated with lobbying money from the same. Some in Congress challenged parts of the law, or even sought to repeal it entirely. Of the 398 deadlines set for regulators to write the rules for implementing the law, 280 — or about 70 percent — have come and gone, and 61.4 percent of them were missed. The Volcker Rule, one of the law’s most powerful elements, was supposed to go into effect over a year ago but has yet to be implemented. The Government Accountability Office said in January that one of the major challenges slowing regulators was “extensive industry involvement through comment letters and litigation resulting from rulemakings.”

The Sunlight Foundation, a nonprofit that tracks money in politics, writes:

By most accounts, the banks’ besiege-the-regulators strategy has yielded rich rewards in sapping, slowing, and stymieing regulations intended to prevent another massive financial crisis. The emerging consensus is that Dodd-Frank implementation is limping, while the big banks are poised to return to being the most profitable industry in the U.S.

Dodd-Frank, in its final form, will be a lot more comfortable for Wall Street than the lawmakers who wrote the law would have hoped. The coal industry hopes to achieve the same thing with the EPA’s regulation of power plant emissions.

But they may not succeed. In a recent story for The National Journal, Coral Davenport writes that the coal lobby feels existentially threatened — more so, at least, than our country’s banking elite.

Coal is under siege from forces beyond its control. Its dominant place in the American economy is slipping—and so, for the first time in a century, is its ability to get what it wants from Washington. There are two big reasons for this. The first is economic: Over the past two years, as a glut of cheap natural gas has flooded the U.S. energy market, coal has been pushed out. The second is more existential: The world is waking up to the fact that pollution from coal-burning plants is the chief cause of global warming. Although some coal companies still deny that, governments around the world don’t—and they are pushing policies to end coal’s use. In the U.S., President Obama is deploying the full force of his executive authority to crack down on climate change. Coal is now reckoning with its role in global warming, whether it likes it or not.

But stricter regulations on burning coal in America wouldn’t necessarily be a nail in the coal industry’s coffin. As domestic natural gas production has increased, coal has successfully found overseas markets for their American product. United States coal exports hit a record 126 million short tons last year.