William Jennings Bryan on the stump. (Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

Historians like me are sometimes described as professional gazers into the rear view mirror to tell us what’s ahead. That’s not quite right; the mirror isn’t a crystal ball but a spotlight into an attic full of lookalike things to think about. Recently I have been thinking a lot about the election of 1896. It occurred in the midst of America’s First Gilded Age and reverberates now in the midst of our second great era of vast inequality between those at the top and everyone else.

Let’s imagine ourselves in 1896. The robber barons — “captains of industry” as they and their purchased politicians preferred to call them (the “jobs creators” of their time) – are not only reveling in their private fortunes but putting that wealth to work accumulating more political power to help secure their control of the economy. Common people are suffering in the third year of a major depression. Workers lucky enough to find jobs put in long brutal hours to earn a pittance. Wheat, corn and cotton farmers are being crushed between falling crop prices and the exorbitant railroad, storage and interest charges imposed on them by the trusts and corporations that have no fear of criticism from governments they have bought off. If unlucky weather or a plague of insects destroys their crop, these struggling farming families are pushed to the edge of starvation.

Meanwhile, the upper classes are sheltered not only by their ability to buy the governments of their choice, but also by a culture which adheres to the pseudo-science of Social Darwinism – “the survival of the fittest” – and the companion academic fiction of “the free market” which holds that any governmental attempt to interfere with its workings on behalf of the victims of unregulated capitalism’s periodic crises is both counterproductive and wicked. A strong religious sentiment runs through this culture as well, and preachers remind their congregations that any effort to help the have-nots will encourage sloth and dependence among those “lower orders.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Neither Democrats nor Republicans had yet made anything but token attacks on the super-rich. But an insurgency is rising from the grassroots. “Populists,” they call themselves, many of them hardhit farmers trying to reclaim their government from the greedy hands of Wall Street, the embodiment of all that’s grinding them down.

To advance their cause they have organized the People’s Party. Its radical platform includes currency inflation to relieve suffering debtors by abandoning the single gold standard in favor of adding cheaper silver to what’s officially known as “legal tender.” The controversy around that one proposal later creates such an uproar that it obscures the appeal of a longer list of populist demands: a graduated income tax; postal savings banks; government ownership of railroads, telephone and telegraph companies; storage facilities and loans to farmers waiting to market their crops; the direct election of senators; the secret ballot and (to woo labor) the eight-hour day and immigration restrictions.

Looking back for enlightenment, we of the present need to keep those aims in mind. Essentially the populists were fighting to end government by plutocrats so that ordinary people had the chance to rise and achieve a decent standard of living.

When the two major parties hold their nominating conventions Republicans choose William McKinley, governor of Ohio, ex-congressman, and warm partisan of big business and the protective tariff. He wins the nomination without much trouble.

Not so with the Democrats, who gather in Chicago in an atmosphere permeated by acrimony. The outgoing president, Grover Cleveland, belongs to the conservative eastern wing of the party, heavily stocked with bankers and corporate heavyweights. They are virtually unanimous in opposition to government assistance to the disadvantaged and equally united in favor of the gold standard. Seething western and southern Democrats with populist leanings are determined that no one from the Cleveland wing be nominated.

They turn to a little-known representative from Nebraska, William Jennings Bryan, all of 36 years old. His nomination comes in the wake of an extraordinary event. Before ballots were cast, a persuasive group of Silver Democrats, mostly from the silver mining states of the Far West, managed to get on the platform committee and asked Bryan to speak at the convention in favor of a contested plank that would incorporate “free silver” into the document;

Bryan already had gained some reputation as a powerful speaker. The Silver Democrats did not know the half of it.

Bryan is both an evangelical Christian and a champion of populist politics who sees reform of the system as a divine mission. A silver-tongued orator, he wastes no time on economic theory, and aims his platform speech directly to the lived experience of everyday people in the distressed agricultural heartland, and at the powerful barons “back East” who had crushed their hopes and aspirations. His unamplified voice reaches every corner of the convention hall as he went straight for the emotions – and hard against the defenders of the gold standard:

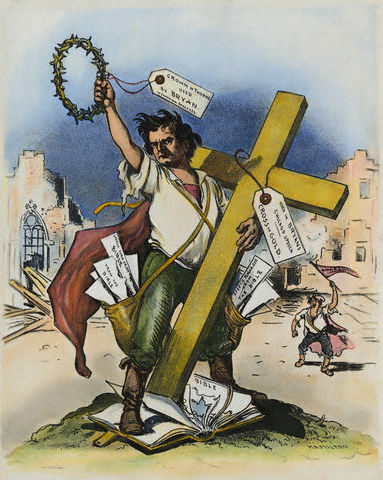

“You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold,” Bryan declares.

Remember, this is 1896. There are no primary elections to choose a party’s candidate. Had there been, the Grover Cleveland Democrats would have built a campaign chest, a wall of gold to block this youthful contender from higher ambition. They do not fear him so much as they do those angry millions of ordinary dispossessed people who are attracted to his message.

American cartoon by Grant Hamilton, 1896, on William Jennings Bryan’s ‘Cross of Gold’ speech. (Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

But the absence of the primary system makes a crucial difference. Bryan’s speech stampedes the convention into roaring demonstrations of approval that go on for nearly an hour. Not only do the delegates embrace the Free Silver plank but the next day they nominate Bryan on the fifth ballot.

At the People’s Party convention held later, the Populists decide to run Bryan as their presidential candidate, too. But because many voters are skeptical of populism and a third party, Bryan makes a point of never officially accepting their nomination. Moreover, although he was in lifelong sympathy with the Populists’ overall democratic reforms, he says little about them in 1896 and is largely a one-issue candidate, focusing on the silver issue, which held little interest for urban workers.

The insurgency had won — but it would now be the turn of the Republicans to halt Bryan’s advance.

Bryan plunges into an energetic traveling campaign — the first in history — touring the country by rail in a journey of some 18,000 miles, with hundreds of “whistle stops” at which, from the rear platform, he speaks some 600 times to an estimated 5 million enthusiastic listeners, pounding home the message of the people’s crucifixion on that “cross of gold.”

His little-known name becomes emblazoned in headlines and he soon has what today we know as “momentum.” Could this heretofore rather obscure politician from a sparsely populated state actually win the presidency?

The prospect puts the fear of God into the 1 percent. He has to be stopped, and if stopping him requires a genuinely savage counter-campaign, so be it.

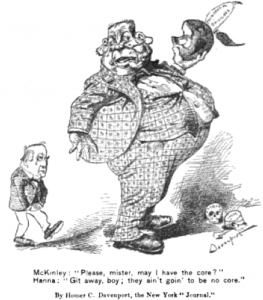

The strategist for the moneyed power’s denunciation of Bryan is a Cleveland businessman named Mark Hanna, whose wealth comes from mining properties and street railroads. One fellow Ohioan said Hanna believed that “the State was a businessman’s State. It existed for property. It had no other function.”

It seems natural to them that businessmen should run the government for their personal profit. Hanna, by the way, is the idealized role model for Karl Rove (and those like him) who wish not so much to destroy government as simply to capture it for their own use.

Political cartoon of William McKinley and Mark Hanna by Homer Davenport suggesting Hanna would be the real president. (1896, Wikicommons)

As chairman of the Republican National Committee, Hanna acts quickly. Money is no stranger to politics — voters had long been wooed with banners, buttons, barbecues and cash “encouragements.” But Hanna knows that in a huge economy, the scale of persuasion needs to be upped. He travels to Wall Street to remind bankers and treasurers that the flames of socialism and anarchy will spread to their own doors if not quickly doused. He shakes them down for contributions of a small fraction of their vast (and still untaxed) incomes. He raises several millions of dollars with purchasing power worth 20 times that today compared to the $450,000 or so that rich silver miners gather for William Jennings Bryan.

The result is a well-financed propaganda campaign disseminated via thousands of pamphlets printed in a variety of languages. A speakers bureau sends more than 1,400 lecturers into every town of reasonable size. Their messages feature one powerful argument: abandoning the gold standard would be a universal disaster. Without “sound money” no investor in the world would risk entering a contract. Business would collapse and, most devastating to workers, factories would be abandoned, taking jobs with them.

This gospel of fear decimates Bryan’s vote in the cities, while McKinley’s campaign promise of “A Full Dinner Pail” becomes a magnet for workers who come to believe that their whole futures now are permanently bound up with prospering industry.

By Election Day, the passions unleashed turn out a record number of voters, some 14 million — 80 percent of the eligible population. The popular vote is close, with McKinley winning by only 51 percent. But the Electoral College tally shows that because Bryan’s votes have come from less populous states. he garners only 176 electoral votes to McKinley’s 271. William Jennings Bryan had risen in combat against Money Power but Money Power buried him under an avalanche of dollars.

There are strong links between the campaign of 1896 and the campaign of 2016. The explosive growth of enormous wealth concentrated in a few hands gave America its first Gilded Age with its attendant miseries. But their corrosive effects brought about the insurgent spirit that eventually will always rise against injustice. When the two forces collided they brewed volcanic passions that almost tore the country apart.

The rebellions in both parties this year mark an uprising against our second Gilded Age, with excesses greater than ever. Bryan wrote a memoir of his struggle and titled it, prophetically, The First Battle. This election year is the latest re-enactment of it. We should expect a campaign that will be outrageous, passionate and wastefully, tragically expensive. Its outcome will either mark the beginning of the end of the reign of King Money or its perpetuation beyond our generation.