This 2002 episode of NOW with Bill Moyers looked at the digital future of intellectual property. Mega-media companies were spending millions to buy influence in Washington, and Congress had recently extended the term of copyright — giving corporations control of intellectual property for far longer than the framers ever imagined. NOW investigated the future of copyright in the digital age and the debate that pits private control against the public interest.

In the next segment (jump to read): Conservatives call it the Death tax. Lawyers call it the Estate tax. Others call it the Inheritance tax. In 2001, a small group of wealthy families successfully campaigned for the repeal of the Estate tax. In 2002, there was a campaign to restore it — led, believe it or not, by some of the country’s richest people, including Bill Gates Sr. and Chuck Collins, heir to the Oscar Mayer fortune. They spoke with Bill about why an inheritance tax is fair and responsible.

Finally, NOW sat down with leading epidemiologist Devra Davis, who spent her career researching the effects of the environment on health. Her book, the WHEN SMOKE RAN LIKE WATER, was inspired by the 1948 industrial smog that killed more than 60 people and made an additional 6,000 ill in her hometown of Donora, PA.

TRANSCRIPT

MOYERS: Welcome to NOW. We begin with a headline from the Supreme Court this week.

It’s from the USA Today Web site and it says “Court Protects Mickey Mouse.” But read on.

It’s not really Mickey Mouse who has the friends in high places. It’s the Disney Corporation and a host of other huge companies like Disney, companies that control the television and movies we see, the music we hear, and even the news we get.

These mega-media companies spent nearly $150 million over the last 12 years to buy influence in Washington.

And in 1998, their investment paid off.

Congress voted to extend the term of copyright, giving these corporations permission to keep control of Mickey for much longer than the law had allowed.

Now, why should you care who owns Mickey Mouse?

Well, if you’ve loaned a friend your copy of the latest SIMPSONS, or printed an article from a Web site, or if you want to copy a chapter of a book at the local library, you could wind up breaking one of these new laws, unless you pay these corporations for what you’ve been doing all along for free.

These add up to a profound issue for our country’s democracy.

Here’s our report by NOW Producer Greg Henry and NPR Correspondent Rick Karr.

RICK KARR: The buzzword right now in the media industries is “digital”. As in, Digital Cable, offering you five hundred channels of news and movies and sitcoms and music around the clock. As in, Digital Video Discs — DVDs — bringing you the clearest picture and the best sound. Media executives say “digital” means consumers have more options. Jack Valenti is chairman of the trade group the Motion Picture Association of America.

JACK VALENTI, CHAIRMAN, MOTION PICTURE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA: We want to build a digital future that will win the admiration of American families, to give them wider choices of movies in a place they want to watch them, in their home, at their command, at the time they want it.

RICK KARR: The “digital” future isn’t just for entertainment — it’s affecting the way you receive news and books, too. It may sound like science fiction, but technologists say that within a few years, you’ll get the latest John Grisham novel, your daily paper, and all your magazines on something that looks and feels like a sheet of paper but that changes the text every time you “turn the page.” Pat Schroeder — the former crusading member of Congress from Colorado — is now lobbying on behalf of publishers as president of their main trade group. She says digital technology — the power of computers — promises readers a lot of new options.

PAT SCHROEDER: The simplest example of where we might go with this would be, say you’re taking a trip. You may want two chapters outta one travel book, a chapter outta something else, your favorite poems from someone about that.

You may want some information on cooking. You just put that all together in your own little digital product. But you pay for the bits and pieces that you assemble.

RICK KARR: But amid the promise of a bright future a growing chorus of lawyers, librarians and educators says the promise comes at a price — that, for example, you might have to pay every time you want to read your favorite novel or listen to your favorite song. And, they say, you’re losing freedom: to record a TV show and watch it later; to photocopy a page out of a book; to e-mail a news article to a friend. And someday, the critics say, you may no longer be able to check a book out of the library.

The central question in the debate over the digital future is…Do we want to treat, movies and music and books and even the news we read in the paper or see on television as products of commerce or as parts of our culture? Are they private property or are they public goods? Are they ways for some people to make money or are they things that enrich our society and the world we live in?

And the moneymakers are winning, according to Eben Moglen who teaches copyright law at Columbia University because the very technology that promises the digital future allows the media conglomerates that own record companies, publishers, Hollywood studios, and major news outlets to take control of the way people interact with culture. Moglen says things could turn out to be pretty dark for the typical American of the future.

EBEN MOGLEN, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW: She can rent music for her Saturday night party, a thousand songs, and they erase themselves again on Monday morning.

She can get an E-book delivered to her pocket, the newest Robert Ludlum novel and it will be there until she’s read it once or twice or five times. But she can’t lend it to anybody. She can’t even print a page of it on a photocopier to show somebody to say, “Here, you’d really love this novel.”

And not only has she lost rights that we take for granted, to make a private copy, to share, she’s also lost privacy, because somebody knows about everything she reads and everything she watches and everything she listens to.

I call this giving people everything they want without letting them keep it. And it seems to me a pretty insidious form of culture.

KARR: It adds up to media companies controlling what you do and how you access culture. And it’s already happening.

Now let’s say you bring home a DVD, and you decide you want to skip over the trailers at the beginning. If the studio that released the disc doesn’t want you to be able to do that, you can’t. In other words, the studio can disable the fast forward button on your DVD player. And there’s nothing you can do about it.

The technology that disables the fast forward button also keeps you from making a copy of the DVD to share with a friend.

Media executives say that the law should allow them to exert that kind of control — they own the rights to the material. But that makes your home computer THEIR enemy because it’s an excellent copying machine. Every time you double click and open something, you’re actually making a perfect copy of the original. It comes onto the screen for you to see — but you can send it onto the Internet for anyone to see. And media executives say that’s stealing.

JACK VALENTI: A 12-year-old, with a click of a mouse, can send a movie hurtling to all of the five continents. So, it’s a kind of piracy, a kind of pilfering and theft that causes more than a few Maalox moments to the movie industry.

We’re trying to have some kind of sturdy protective clothing put on these movies.

RICK KARR: That “sturdy protective clothing” — so far — has been technology. But publishers, movie studios and record companies have also lobbied Congress to change the laws that govern “intellectual property.” They want tighter control over it and they want to own it longer.

This discussion actually dates back to the Framers of the Constitution, who wrote protection for “intellectual property” directly into Article One, Section Eight where Congress is given the power “…to promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors the exclusive right to their writings.” Today, we know that idea as copyright.

Copyrights are exactly what the name implies — the right to make a copy of a book or a movie or a song or a photograph.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY: This is what’s known as the copyright bargain. We, the people, grant this monopoly power to a copyright holder. Because we feel it’s important for the copyright holder to be able to make a living. Or, at least try to make a living.

In exchange, we get something back at the end.

RICK KARR: Siva Vaidhyanathan is a cultural historian at New York University who’s written extensively on copyright.

SIVA VAIDYHANATHAN: The founding fathers clearly saw that without an indigenous literary industry, information industry, book industry, we weren’t going to be able to operate as responsible democratic citizens. So, copyright was all about making sure that we were able to develop that sort of industry.

Vaidhyanathan says that that industry is now dominated by a handful of multibillion-dollar media conglomerates. In 1998, they successfully lobbied for a law that Vaidhyanathan says gives them unprecedented power to protect their “intellectual property.” The Digital Millenium Copyright Act makes it a federal crime to diminish a copyright holder’s control over digital books, music and movies. Media executives say the law is supposed to stop piracy.

JACK VALENTI: Well, it’s not so much keeping control. It’s to keep something from being stolen from you.

RICK KARR: Siva Vaidhyanathan says the law keeps Americans from doing things that have always been legal because it effectively eliminates a right known as fair use. That allows students and professors to quote things in class or scholarly papers. It lets scientists refer to one another’s research and comedians parody TV shows. With fair use, we as journalists can show excerpts of copyrighted work — say, the nightly news — in order to comment on events without asking permission or paying a fee. And every American with a VCR is allowed to tape shows and watch them later. Under the new law, Vaidhyanathan says, that’s no longer the case.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Fair use is one of the most important democratic safeguards in copyright.

Copyright could be used as an instrument of censorship. It wouldn’t be very hard to imagine a world in which complete power over copyright can stifle anybody else from using a person’s material for criticism or commentary or parody.

RICK KARR: Media executives say that’s scaremongering — Pat Schroeder of the Association of American Publishers says she finds the public’s ability to make copies at will MUCH more frightening because it could end up destroying the book business.

PAT SCHROEDER: Now, if suddenly you say when a library buys one digital copy they can then give it to the world and they can go out and make their own copy, we can visualize a world where you would sell one digital copy and that would be it.

RICK KARR: Publishers and other media companies have been aggressively enforcing their digital rights. In 2001, a corporate lawsuit shut down the music “file sharing” service known as Napster. Critics fear the new legal climate could eventually kill off the public lending library, as well.

Nancy Kranich is past president of the American Library Association.

NANCY KRANICH, PAST PRESIDENT, AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION: In copyright law we have what we call the “first sale doctrine,” and that allows us to actually physically purchase a book, for example. And we can do anything we want with that book. We might sell it, we can catalog it, we can discard it, we can use it any way we want, but that right within the copyright law is the basic right of how libraries exist.

RICK KARR: She says libraries are already losing their ability to loan things out because publishers don’t sell digital books to libraries — they “license” them.

NANCY KRANICH: Most of the materials we’re getting electronically we’re signing licensing agreements for, and the licensing agreements set the contractual terms for how the public or how we will provide access to this information as opposed to the materials we were buying before basically followed what was in the copyright law. Those were the terms, were set.

RICK KARR: So what used to be a matter of public policy is now a matter of private contract.

NANCY KRANICH: Exactly.

RICK KARR: Kranich worries that everything that libraries can do today for free — loan a book to you or to another library, or allow you to photocopy a page — will cost money in the future, each and every time it happens. During a budget crunch, a library might not be able to pay the “rent” on a digital book, so to speak. And so the book will disappear from the library’s collection.

Critics of the new copyright law say media companies have expanded their control in another way: by keeping things out of the public domain.

EBEN MOGLEN: The public domain is all the creative works that are available to everybody because copyright on them has expired or never was entered in the first place.

The King James version of the Bible, all the plays of Shakespeare, MOBY DICK, the recordings made at the very beginning of the 20th century by Paderewski, of the music of Chopin.

Whatever is not under copyright now is available for us to make what we wish of it.

RICK KARR: Corporations can borrow from the public domain, too, to make profits and to add to the culture.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: You can look at Disney films over the course of the last century, and — CINDERELLA, MULAN, ALADDIN, SNOW WHITE. These are all works that came out of the public domain. They’ve been reinvigorated and rolled out in new forms and they’ve made a lot of money, and they’ve made a lot of people smile.

The public domain is a rich source of creativity. Congress, though, has stopped up the replenishment of the public domain, ironically, at the behest of the Disney Corporation.

RICK KARR: Over the decades, Congress has extended the term of copyright — from 28 years to 56 years and then to the life of the author PLUS 50 years in 1976. Still, media companies feared they’d lose some of their most valuable “property” to the public domain. For instance: “Steamboat Willie”.

The first screen appearance of Mickey Mouse — made its debut in 1928 and was supposed to go into the public domain — and become freely available to everyone — next year. Eben Moglen of Columbia University says Disney and other studios lobbied Congress to extend copyrights.

EBEN MOGLEN: I think that the copyright extension happened precisely to make sure that all of the works of mass communications culture, remained in the hands that already owned them, and did not return to the public on the schedule the copyright law would otherwise have provided.

RICK KARR: In 1998, Congress voted unanimously to extend copyright protection by an additional twenty years. In the two years prior to that copyright extension, Disney and its employees contributed more than $1.2 million to federal political campaigns; film, television and music companies gave more than $16 million.

And there’s this new development: a legal challenge to the copyright extension law went all the way to the Supreme Court. Just two days ago, the Court gave its stamp of approval to Disney and other Hollywood studios. “Steamboat Willie” won’t come into the public domain until 2024 at the earliest.

Siva Vaidhyanathan says copyright law is supposed to benefit creative people — artists, musicians, and writers. But ironically, he says, the recent changes have made it harder for them to mix and match the ideas and images that they find in the culture.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: They’re wondering if the terrain has changed on them. They’re wondering if they can do what Andy Warhol did. And unfortunately, the answer is, less and less. You can do less and less.

We are in serious danger here, because we have altered the law. But just as importantly, we’ve altered the culture. Actually, more importantly. We’ve taken the fun and the play out of our culture. And that is going to create a creative dark age, if we’re not careful.

RICK KARR: There’s yet another school of thought on copyright in the digital future: That the law and technology don’t matter, because people are going to do what they will. And that that may not be so bad for business.

JIM GRIFFIN, CHERRY LANE DIGITAL: I don’t think it’s inconsistent at all to point out that in the history of intellectual property, the things we thought would kill us were later the things that fed us. And that’s been true almost uniformly.

RICK KARR: Jim Griffin is president of the Los Angeles music company Cherry Lane Digital. He says there’s a historical example of a new gizmo that the media industries found threatening — the VCR. In the early 1980s, film industry lobbyist Jack Valenti said that home videotaping would destroy Hollywood.

VALENTI [IN 1984]: For if what creative people produce cannot be protected, if the value of what they have labored over and brought forth to entertain the American public cannot be protected by copyright, then the victim is going to be the American republic and the inevitability of a lessened supply of a high quality expensive high budget material where it’s investment recoupment is now in serious doubt.

RICK KARR: But Hollywood was wrong: Ten years later, videotape sales and rentals generated about the same amount of income as box offices and movie attendance was rising.

JIM GRIFFIN: When the video cassette recorder comes out, it’s lawyers and technologists that try to deal with it. The lawyers file a lawsuit against Sony. And at the same time, technologists try to find a way to control it, too. Someone develops a video cassette that has a ratchet in it, so that you can’t rewind it and watch it more than once.

And ultimately, both of these groups fail. The lawyers in historic retrospect, serve only to delay the arrival of billions of dollars of new income. And the technologists never come up with a way to control the video cassette that’s effective.

RICK KARR: Griffin says it’s happening again: Consumers, he predicts, will always find a way around corporate efforts to control the new digital technologies.

JIM GRIFFIN: There is no solution to these problems that does not involve government. I wish it were otherwise.

RICK KARR: Griffin favors a radical approach: Laws that would establish entirely new ways of paying authors and creators while at the same time guaranteeing open access to consumers.

But Pat Schroeder prefers laws that would let the industries roll out the digital future that they want.

PAT SCHROEDER: The copyright industries have greater exports than automobiles, than aircraft, than agriculture. But Americans don’t know that. So, they yell that “Oh, well, Congress is protecting the copyright industry.” Well, Congress protects agriculture, automobiles, and others. And aircraft, for heaven’s sakes. Of course they ought be to protecting the copyright industry.

RICK KARR: But critics worry that publishers, film studios and record companies — and their millions in campaign contributions — will drown out the public interest when legislators consider future copyright laws.

JIM GRIFFIN: Equalizing access to knowledge is one of the hallmarks of a civilized society. Depriving people of access to knowledge based on the size of their parents’ wallet is a hallmark of a despotic society.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: We’re allowing the content holders, the content producers, to have a remarkable amount of control over the manner and amount and re-use of all this material. We don’t want to build a cultural environment, in which the media companies have that much control over our daily lives.

RICK KARR: Vaidhyanathan wonders who will remind Congress that the public has an interest in the copyright bargain, too — and that what’s good for commerce isn’t always what’s good for culture.

MOYERS: Congress got a reminder of the public interest this week from Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer.

The court, by a vote of 7-2, upheld the authority of Congress to extend the term of copyright, even as that term gets far longer than the framers ever imagined.

Justice Breyer dissented.

And in his dissent, he quoted previous decisions about the copyright clause.

His argument says copyright:

“exists not to provide a special private benefit…but to stimulate artistic creativity for the general public good… Copyright was not designed primarily to benefit the author of any particular class of citizens, however worthy… Rather, under the Constitution, copyright was designed primarily for the benefit of the public; for the benefit of the great body of people.”

That sentiment and those words, “the great body of people,” are heard so seldom in Washington these days.

They sound almost quaint, don’t they?

Conservatives call it the death tax. Lawyers call it the estate tax. I grew up hearing it called the inheritance tax. And therein lies a story of wealth and power.

After a 10-year campaign hatched by a small group of wealthy families, Congress repealed the tax in the year 2000. Their crusade climaxed with a PR campaign that made it seem the estate tax was about to kill off the family farm.

The law repealing the tax was delivered to the White House on a bright red tractor but President Bill Clinton wasn’t buying. He vetoed the bill and the estate tax continued. No sooner had George W. Bush reached the White House, however, than he made repeal of the tax a big priority and Congress of course was happy to oblige. The day after he signed its repeal the President was out in Iowa talking about it.

[CLIP OF PRESIDENT BUSH SPEAKING IN IOWA]

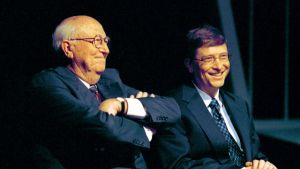

William H. Gates, Sr. and his son Bill Gates, chairman and chief software architect of Microsoft, are introduced during a lecture at the University of Washington in Seattle on May 4, 2001. (AP Photo/Andy Rogers)

But the story doesn’t end there. There’s a campaign to restore the inheritance tax. And it’s being led, believe it or not, by some of the country’s richest people including Bill Gates, Sr., the patriarch of the Gates family who heads the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Chuck Collins, an heir to the Oscar Meyer fortune who founded the organization called Responsible Wealth.

They’ve written this new book arguing for the inheritance tax. It’s called WEALTH AND OUR COMMONWEALTH. And they’re here to talk about it with me now. Thank you very much.

True or false: many family farms must be sold off to pay for the Federal taxes due on them when the owner dies.

COLLINS: That’s false. A number of investigative reporters have gone out to the midwest, they even went to Iowa, and they asked the American Farm Bureau, one of the proponents of repeal, to produce a single example of a farm that had been lost to the estate tax and they could not find one.

And they…the president of the Farm Bureau even sent out an urgent e-mail across the country saying, please, send us examples — but produced none.

MOYERS: What about that rancher or farmer on that red tractor that delivered the bill to the White House in 2000?

COLLINS: That’s an interesting case, because that rancher from Montana, we looked up his name and we found that over the last five years he’s received $450,000 in farm subsidies from us the taxpayers. We the taxpayers have been an enormous investor in the Cornwall Ranch in Montana.

MOYERS: That’s his ranch.

COLLINS: We are…we’re sort of joint partners if you will.

And when he passes that farm on upon his death, we think that the taxpayer should have a claim back on that. It’s just, this notion that we did it all ourselves, that is the great big myth here. And that’s not to dismiss individual efforts; it’s more that we just don’t look enough at the role that society plays in helping people create wealth.

MOYERS: True or false, Bill Gates, Sr.: the estate tax is a form of double taxation because you pay when the money is earned and again when you die.

GATES: Well, we do that all the time. You know, double taxation, or the elimination of double taxation, is not an axiom of tax law.

The cardinal example of course is the home I live in in Seattle. I’ve been paying taxes on that home for 40-some years, year in and year out. And that’s not double taxation. We tax property, we tax it regularly. We tax transactions.

The passage of an estate from one generation is a transaction. And that’s the proper way to look at it. It’s in effect an excise tax. And we tax gifts, we tax sales, we tax transactions …but that’s not double taxation; that’s just the way it works.

MOYERS: Why are you doing this? I mean, haven’t you declared class war on yourselves in a sense?

GATES: Well, you know, it just…to my eye, it’s just a question of fairness. It disturbs us, for example, that here we have a significant ingredient of the Federal revenue stream which people are taking away at the very time that our government is going to need revenue at a level that is unprecedented. We’re talking about $200, $300 billion deficits now.

And the notion of repealing a tax in the midst of that situation leads inevitably to the proposition that some other tax is going to have to take its place.

MOYERS: And your case in the book is that if the wealthy don’t pay their share, then working people have to pay a larger share.

GATES: That’s it exactly.

MOYERS: But isn’t it the problem you’re up against, that is, that wealth is increasingly concentrated in the top one percent of this population and they’re the ones making the largest and most consistent contributions to the political class, so you’ve got a system that is being…against what you’re trying to do.

GATES: Bill, that’s precisely true.

COLLINS: We should be concerned about the estate tax repeal precisely for the reason we have an estate tax, which is to prevent the wealthy and powerful from writing the rules and changing the rules of our culture and society.

MOYERS: Was there a moment of “a-ha!”? A moment when you said, I mean, you’re a private man, a taciturn man. Was there a moment, though, when something happened that caused you to say, I’ve got to go public on this?

GATES: Well, actually there was. I was on an elevator in an office building in Seattle and I had a friend who was…I was not aware of, but a friend who had been working on this for some years in the Congress who made the statement to me, he said, Bill, I’m about to bring to fruit of many years of effort. I think the Congress is about to repeal the Federal estate tax.

And I felt as if I had been hit in the chest with a baseball bat. I just thought, oh, no! That is just ridiculous. So…

MOYERS: Why did you think it was ridiculous?

GATES: It’s just such a fair tax. I mean, it’s just such an opportune, appropriate time to have repaid from the people who have benefitted more than anyone else from the circumstances that this country makes available, from the conditions that make it possible to become….

There’s nowhere else in the world, nowhere else in the world, that people can accrue the kind of fortunes that happen here. And that’s because of the kind of country we have.

And the kind of country we have is a function of the taxes that we pay to provide security, we have a stable market, you can predict next week will be pretty much like the week before.

We have the most immense investment being made by our government in advancing businesses by supporting the enormous research industry that’s going on in this country. And it’s that piece of government expenditure that which has everything to do with the health and robustness of our economy.

COLLINS: We believe that people who accumulate great wealth also have been lucky, have had the benefit of growing up and living in the United States, and have benefitted from this enormous public investment.

One of our leaders in Responsible Wealth was standing next to President Clinton when he vetoed the repeal of the estate tax and he said, look, I grew up in New York City, I went to public schools and public libraries and museums. Someone else paid for those.

I went to a college; someone else paid for that. I went into the technology field, a whole infrastructure that had been built with public investment that someone else had paid for. I started a company and I hired professional people who had been trained through a subsidized education system. And I made $40 million. And you’re telling me society doesn’t have a claim on my wealth? You know…

MOYERS: You gave away much of your fortune, didn’t you, when you were a young man?

COLLINS: I did when I was 26, and I…it partly was just out of this sense that I needed to make my own way, and that too much inherited wealth was actually maybe an impediment to my own…making my own way in life.

And I think we’re a country that’s better off when there’s less great concentrations of inherited wealth and more real equality of opportunity where everybody can have a shot at the starting gate of life to make a difference.

MOYERS: Why shouldn’t you be able to direct your money to where you want it to go in your will or however you want to do it? I mean, you earned it.

GATES: “You earned it” is really a matter of “you earned it with the indispensable help of your government.”

You earned it in this wonderful place. If you’d been born in West Africa, you would not have earned it. It would not have occurred. Your wealth is a function of being an American.

GATES: The huge disparity in wealth that’s happening, is something that is, I think, really dangerous.

MOYERS: Why?

GATES: Wealth is power, Bill. And it just is not a good situation. And the examples of the aristocracies of Europe are so clear. We don’t want to have a country like that. Who was it that said, it was Louis Brandeis who said…

MOYERS: Justice of the Supreme Court…

GATES: Yes, indeed. And he said, you know, we can either have a situation where we have a small number of people with a huge amount of wealth or we can have a democracy. But we can’t have both. That’s clear wisdom.

MOYERS: Are we living in a new gilded age…do you fear that we’re living in that kind of time again?

GATES: I do. I do. You know, the data is very clear. We have this enormous accretion of wealth in the top levels, and it’s hugely out of balance. The disparity is very disturbing.

COLLINS: The establishment of the estate tax in 1916 was in a sense a response to the excesses of the first Gilded Age a century ago, that there was a social movement of farmers and workers, people like Andrew Carnegie and Teddy Roosevelt who said, we should have an estate tax because too much concentrated wealth is going to backfire and create an American aristocracy.

So both that and the circumstances of World War I led to the push for an estate tax. And here we are entering the second Gilded Age, a period of incredible dizzying inequality and also new obligations in terms of defense and security spending.

It’s unprecedented to think about repealing a tax on the very wealthy in such a circumstance, and yet that’s what is being talked about.

MOYERS: And do I understand correctly that you’re not advocating that the government take everything that somebody passes on to children?

GATES: On the contrary. No, we’re not. We’re saying, for example, that if the exemption were three and a half million dollars or $7 million for a family, that…. And the rate was say, 50 percent just as a for instance, then whatever dad and mom leave in excess of $7 million, and half of the rest, still there for the children.

COLLINS: This has been kind of framed as an all or nothing debate, and I think that’s been part of the challenge. It’s either keep the estate tax as it is or get rid of it. And for the last few years people have put forward reform proposals.

President Clinton said he would have signed a proposal that would have raised the exemptions immediately to about $3 or $4 million. The problem is that the forces of all or nothing repeal have blocked those proposals. They voted against them because they understand that if those exemptions are raised they’re not going to be able to find telegenic farmers and small business owners who are going to be able to stand up, they’re going to be…they’re hard enough to find now, and they’re going to have a very hard time making the case that this is a tax that really does reach down and injure small entepreneurs.

MOYERS: What do you think is the social harm that comes from a large concentration of wealth?

GATES: I just don’t think that my son’s children or any other wealthy person’s children are benefitted by being handed a quantity of money that’s so great that they and their offspring will be really rich for that generation and for generations to come. That’s not a good thing for a human being, to be in that situation.

And then more to the point, it’s not a good thing for society.

COLLINS: I have a six year old daughter, I don’t want her to grow up in a society where we have essentially an aristocracy of power and privilege. That would undermine the quality of life for everybody.

So we’re not trying to sound like selfless people here; it’s what kind of country do you want to live in? What kind of world do we want to live in?

MOYERS: What do your two daughters think about this? I mean, in effect, you’re going to cost them something when you’re gone!

GATES: Well, I think I can fairly describe them as being understanding of what’s happening here.

MOYERS: So you are in effect penalizing them because of your principles.

GATES: That is correct, but I’m doing the right thing.

MOYERS: But isn’t it true that wealth helps create wealth? I mean, some rich people do very good things with their money. Andrew Carnegie built all of those libraries. I served on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation, they’re helping to nurture the Green revolution. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation crusading for public health around the world. I mean, would you be able to do that if your money were confiscated by the government?

GATES: Well, as you know, Bill, that choice is available to everyone. We’re not arguing about something that would change that whatsoever. The charitable gifts will be still be a deduction in computing estate taxes. So a wealthy person has an absolute choice as to whether they pay the tax or whether they give their wealth to their university or their church or their foundation.

COLLINS: Actually, on the other side, if you…if we eliminate the estate tax, we think that there will be…we know from the research there will be a tremendous decline in charitable bequests and giving. And that’s not to say that people give simply because of the tax code, but for a wealthy household with $20 million or more, the estate tax is a major incentive. Some $8 to $9 billion a year will be lost from the charitable sector if the estate tax is repealed.

MOYERS: So what’s the strategy? What happens now?

COLLINS: Well, in the coming months the proponents of eliminating the tax will try to once again bring up legislation to make repeal permanent.

And they need 60 votes to do that. And we estimate they have about 57. So we’re going to be out there basically making the case that we’ve made here, during a time of tremendous budget deficits, we should not eliminate the most progressive tax we have.

And we’re going to try to pull back and win over new allies, people who maybe under different circumstances voted for repeal but under the new current fiscal situation will vote against it.

MOYERS: Who are the swing votes?

COLLINS: There’s some key people, the Senators from Maine, Senator Snow and Senator Collins, voted for repeal. Senator Arlin Spector voted for repeal.

MOYERS: Three Republicans.

COLLINS: Senator Ron Wyden from Oregon…

MOYERS: Democrat.

COLLINS: …a Democrat, voted for repeal. We’ve identified about a dozen Senators. Senator Voinovich from Ohio, voted for repeal but he’s somebody who’s been a governor, he’s been a mayor, and he knows how hard it is to deal with fiscal issues. He’s making noises that he’s rethinking this issue.

MOYERS: If someone was to get in touch with the organization, Responsible Wealth, how do they do it?

COLLINS: They can visit us on the Web at responsiblewealth.org.

We have an online petition that people can sign supporting reform but not repeal of the estate tax. And ..we have over 1,000 people who would have to pay the estate tax who have signed it saying it should be preserved. And I think that’s an interesting story.

MOYERS: Thank you very much, Chuck Collins and Bill Gates, Sr., authors of WEALTH AND OUR COMMONWEALTH.

COLLINS: Thank you, Bill.

MOYERS: Now joining us in our studio, NPR’s Jacki Lyden.

LYDEN: How can we protect our inheritance when it comes to the environment? You’re about to meet a woman who has spent her entire career researching the effect of the environment on health.

Devra Davis is a Visiting Professor of Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University, a senior advisor to the World Health Organization and the author of this book, WHEN SMOKE RAN LIKE WATER, a story that’s not only scientific but personal.

Devra Davis, welcome to the show.

When it comes to America, at least, for the last couple, few decades, the air has been getting cleaner.

Why should we care now so much about air pollution?

DAVIS: Well, in fact, the air quality in the United States today is generally better than it has been in the past, but we understand something different about air pollution.

We now understand that current patterns of air pollution endanger public health today in subtler ways than we ever appreciated.

Whether increased rates of asthma, increased problems of health are associated with living in dirtier areas, even though we are much cleaner today than we used to be.

But we also know something else, which is the same things that contribute to local and regional air pollution– burning of coal and burning of gasoline and burning of diesel fuels– those same things also produce greenhouse gases.

These are gases that warm the planet over all, things like carbon dioxide and methane and some of them will live for a hundred years in the upper atmosphere making the planet warmer.

LYDEN: And while other contaminants have declined, greenhouse gases are one of the things that are on the increase?

DAVIS: The average American burns the equivalent of two SUVs worth of coal and sends it up into the air every year because of our current patterns of energy use, so greenhouse gases are continuing to grow.

In fact, in the United States today, we are burning 12% more greenhouse gases now than we did in 1990.

LYDEN: I want to get to your personal story, because you’re an epidemiologist.

First of all, in your book, you even write about what that means, epi and demos.

DAVIS: Well, an epidemiologist comes from two Greek words: “demos,” Meaning people; and “epi,” meaning upon.

And epidemiologists look for patterns upon the people, how diseases and pollution are related in time and space.

And the field of environmental epidemiology is probably the toughest field we have to do that research in, because we can’t control all of the things that go on in the environment broadly, so we’ve got to look for natural experiments, if you will, catastrophes that happen, explosions or accidents, where we can go back and ask what has gone on and what might explains patterns of health over time and space.

LYDEN: And sadly, you grew up with one of the catastrophes which became an environmental landmark in this country, Donora, Pennsylvania, a town I confess that even though I was once a steel reporter and covered the demise of the steel industry, I had not been to Donora nor heard of it.

It’s in the Monangahela Valley.

Tell us about what happened in Donora, Pennsylvania in 1948 when you were a girl.

DAVIS: Well, when I was a very small child, at the end of October, around the time of Halloween, a massive inversion of cold air settled over the valley and hot fumes were trapped in a kind of sandwich layer with cold air on the bottom, fumes, and a layer of cold on top.

And they couldn’t get out of this area where there were steel mills and coke ovens and coal fire furnaces.

And within 12 hours, in one period of 12 hours, 18 people dropped dead in that town.

LYDEN: It’s just incredible to think about.

This became known as the killer smog of Donora.

Why don’t more people know about it today?

DAVIS: Well, I’ll tell you frankly, I didn’t know about it at the time.

I had to go away to school, which I did, to Pittsburgh.

I was a student at the University of Pittsburgh, and my family had moved to the town of Pittsburgh from Donora, leaving the town as did half of the residents because the mills had shut down.

And I came home one day and I said to my mother, “Mom, was there another town with the same name as ours?”

She got kind of quiet and said, “Well, why are you asking?”

I said, “well, I read in a book at school that a town with the same name as ours was polluted.”

And I actually didn’t think at the time that Donora could be the Donora that I grew up in, that I had read about.

And she got kind of quiet and she said, “Well, you know, I guess today they call it pollution, but back then it was just a living.”

And so, you see, the town was employed by the mill, and the factories there.

And so people couldn’t dare think about the possibility that the same thing that kept them employed might also have affected their health.

LYDEN: Let’s look at a clip that we have, Devra, from our member station in Pittsburgh, WQED multimedia.

They made this documentary last year from vintage 1948 footage that was filmed of the killer smog.

[CLIP FROM WQED MULTIMEDIA]

NARRATOR: At first, nobody noticed.

Visibility was just worse than usual.

WOMAN: It was around Halloween time and the kids were all excited.

They were in a parade and you didn’t have to make it spooky, it was already spooky because you couldn’t see very much.

It had a very eerie feeling.

LOFTUS: I was a nurse at the Donora Mill.

NARRATOR: Eileen Loftus was a young woman then, in charge of the nursing staff.

She was called to duty when gasping mill workers crowded the infirmary.

Even at the age of 85, Eileen says she’ll never forget walking to the plant through a blinding cloud.

LOFTUS: And I touched the houses as I went along to make sure I was still on the sidewalk.

The hospital was jammed.

They wanted to know if they were going to live, or what, and I says you’re going to live if I can help it.

NARRATOR: When the funeral homes ran out of space, bodies were taken to the community center, and emergency workers struggled to keep the death count from rising.

20 funerals, grieving families, national headlines, that’s what it took to temporarily shut down the zinc plant.

[END CLIP]

LYDEN: This is truly an incredible story. The smog lasted for five days, 20 were killed immediately. You documented that many more would die the following month.

And life went on as normal. People didn’t know what was happening. The football team played its homecoming game, couldn’t even see each other.

DAVIS: Yes. It was… you have to understand that when you grow up in a world, it’s normal not to be able to see in the afternoon, it’s normal to have the headlights on.

It’s normal to have to scrub the walls down to keep them clean that you don’t know that there’s any other way for it to be.

LYDEN: Tell us what happened in the aftermath of Donora, because it would link directly to the way this country would respond to environmental disasters, indeed to even thinking about the environment as something that could possibly be harmful to us.

DAVIS: What happened of course is the public health authorities came in and did a study.

The study was never finalized.

And it began a tradition with respect to environmental disasters that we still face today, which is it’s a lot easier to study a problem than it is to do something about it.

LYDEN: You’ve written that the people who died in Donora didn’t die in vain because eventually what happened there led to laws passed in the ’60s about cleaning up the air and then into the 1970 Clean Air Act and the creation indeed of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Could you explain a little bit about the relationship?

DAVIS: We were very fortunate to have a brilliant politician as President in 1970 named Richard Nixon, and President Nixon has never been received his full due for being the environmental President that he really was.

He may not have personally cared much about the environment.

In fact, he used to keep a log burning in the White House fireplace in the summertime and had the air conditioning on because he liked the homey feeling.

But as a politician he understood that there was a growing national and international movement demanding a cleaner environment.

And so what President Nixon did was to help create first by executive order the Environmental Protection Agency and to sign into law legislation mandating clean air actions.

Before that, the federal government’s role was basically that of conducting research.

Once President Nixon saw the importance of it, the federal government actually had laws put into place that required actions.

LYDEN: Well, that of course is the debate we have today, how much research to conduct, and when to enact a law.

And some of them have been repealed, certainly the administration is trying to act to repeal some of the Clean Air Act.

They began to do that last November.

What’s your opinion about that?

DAVIS: Well, I would say that there is a serious concern now among a number of people including a number of republicans that this administration is making some fundamental mistakes.

It’s misjudging the American people.

Recent Gallup polls indicate that a vast majority of Americans consider themselves to be environmentalists.

And this is an issue that cuts across all political parties.

And I think Senator McCain is to be applauded for introducing this bill now with Senator Lieberman that says that there’s got to be economy-wide actions taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to increase our efficiency and to move us off of the burning of fossil fuels.

LYDEN: It’s not a precise science, is it? I mean, you write that looking for environmental causation and using epidemiology to do it is a blunt instrument, that it’s very difficult for epidemiologists to say that it’s this precise cause that affected this individual at this point in time.

And so that the standard of proof is not as clear as you’d expect when it comes to causation.

DAVIS: I think that that’s generally true for most of the things that we deal with in the environment.

Think about this.

We really don’t have an unexposed control group.

We have one planet right now.

We don’t have another one to go to if this one doesn’t work right.

And we have lots of evidence now, not just public health evidence, but evidence from climate studies, evidence in meteorology, evidence on air pollution.

We know enough now to know that we have got to become more efficient in our economy, in the way that we use fossil fuels, and we’ve got to move away from burning carbon to a hydrogen-based economy.

That’s very clear.

Governor Pataki has just announced that the state of New York is going to purchase 25% of its energy from alternative sources.

That’s the kind of thing that we have to encourage and see more of, but we desperately need federal leadership, as well as leadership from the private sector to make that happen.

LYDEN: Do you think we’re getting that?

DAVIS: I think that there’s a change about to happen.

I think that I’m encouraged by the republican governors of Massachusetts and New York, and the activities that they are committed to with respect to this issue.

I think it’s clear that there’s bipartisan support at this point.

And we can’t rely on voluntary action. That simply isn’t going to work.

The problem the administration is making is that they assume everybody is as nice as Laura Bush.

LYDEN: And why is Laura Bush sort of a vanguard player here, other than the fact that she’s of course the first lady?

DAVIS: Well, not only is she the first lady, but she had the vision four years ago when she was planning the Crawford Texas ranch of the Bush family to see that that ranch uses passive solar design, recycled waste water, and uses warm water from the earth to heat the floor in the winter.

So it’s pretty much green in a lot of its design, and I think that that’s a wonderful thing, that she had the vision to do.

And I think that that’s the sort of thing we need to see institutionalized because we cannot rely solely on the good motives of a few people.

LYDEN: Are we playing with our health?

You’ve looked at environmental causes, for instance, as to whether or not they’re associated with breast cancer.

Do you think that our alarm factor is about where it should be?

DAVIS: No, I think that there’s good reason to think that a large portion of some cancer today is due to the environment.

In the case of breast cancer, we know that only one in ten women who get the disease is born with a defect in her gene.

That means that women get breast cancer because of something that happens to them after they’re born.

They’re born with healthy genes, and then something happens to give them the disease.

Now some of that is due to agents in the environment — broadly conceived — that affect the amount of hormones in a woman’s lifetime and the way her body processes these.

LYDEN: Can I just ask you about the Long Island breast cancer study which was disputed last summer?

Some of the activists who had commissioned that study, a multi-million dollar study done by the National Cancer Institute and also the CDC, wasn’t really able to determine whether or not there was environmental cause to breast cancer, and yet we do know that breast cancer is a lot more common than it was a century ago.

DAVIS: Well, certainly, and some of the reasons why breast cancer is more common has to do with changes in our population.

Women are having children later in life.

But that cannot explain the increased rate of breast cancer that we’re seeing today where women born in the 1940s are getting twice as much breast cancer as their grandmothers did, and we don’t really know why.

But one of the things that we do know about that Long Island study is that it only looked at a small number of possible causes.

It looked at some pesticides that had been banned 30 years ago and found no difference in women with breast cancer compared to those without it.

But it did not look at some plastics, at some solvents, at some fuels which we know cause breast tumors to grow in male rats when we study them in the laboratory.

These things… If they can grow a breast tumor in a male rat, we have reason to think that they are playing a role for women.

The problem is epidemiology is a very crude tool, and it can…

It’s best suited to studying things that we can measure in the body.

You don’t measure residues of plastics or fuels or solvents 30 years later.

We don’t know why women in Marin County have such high rates of breast cancer, but we know the microelectronics industry and its heavy use of solvents has women workers with increased rates of breast cancers.

So we have a lot of unresolved questions on this, but I would point out it was very interesting to see how quickly people said, “Oh, well, there’s nothing in the environment here that’s going on.”

In fact, that’s a vast exaggeration of that study.

What that study looked at was some pesticides that had long been banned and some things that you could measure in tissue, but it didn’t look at a number of things that you can’t easily measure in tissue.

And it also compared women on Long Island with breast cancer to women on Long Island without the disease.

If you want to find out whether Long Island has anything to do with it, you might want to compare these women with people elsewhere.

LYDEN: I just want to ask you before we finish, do you go back to Donora very often now?

Do you know, have you met some of the people?

I know you mention a number of people in your book, but do you stay in touch with those folks?

DAVIS: I am in touch with a few of them, including a young woman who was one of my close friends in grade school.

And it’s… a lot of really good people are still in Donora, but it’s a shell of what it used to be because the mills are totally shut down.

The only growth industry in the area at this point really are old age homes and small businesses have developed there.

But you know what’s really interesting is it’s green.

It’s literally green.

And when I was a kid growing up we used to be able to slide down the hills, because on some of the hills no grass grew at all.

There was grass in some areas, but in the areas where the plumes would come in, there would be none, and it made great sliding boards for all of us.

LYDEN: And now the grass is growing, the flowers are there.

Devra Davis, it’s been great having you on the show.

Thank you very much.

DAVIS: Thank you.

MOYERS: That’s it for NOW.

I’ll look for your comments on pbs.org.

Our web page visits have doubled since last November so keep them coming.

I’m Bill Moyers.

See you next week.

This transcript was entered on March 27, 2015.