Selma marchers and Ferguson protestors (Photos: Library of Congress/Wikipedia & Debra Sweet/Flickr CC 2.0)

Politicians, activists and everyday Americans will commemorate the 50th anniversary of the historic Bloody Sunday civil rights march in Selma, Alabama, this weekend.

But the fight for equal opportunity in our democracy continues today. All over the country, the American Civil Liberties Union is litigating voting rights cases, including one in Ferguson, Missouri, a city that illustrates how a lack of fair opportunities in the political process both reflects and reinforces broader patterns of discrimination.

Following the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed African-American teenager who was shot dead by a white police officer last year, protesters took to the streets for weeks, demanding equal rights for blacks. The tensions did not arise overnight, but had been simmering for years as severe segregation and vast inequality along racial lines frustrated residents. One need look no further than the Justice Department’s new report to get a sense of the pervasive and systematic problems of discrimination and exclusion in Ferguson.

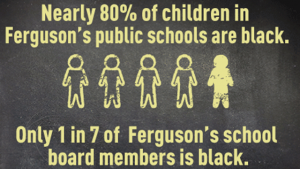

Representation in government follows similar patterns: Ferguson is almost 70 percent African-American, while its mayor, city manager and five out of six City Council members are white. The voting age population of the Ferguson-Florissant School District is approximately 47 percent African-American, as is nearly 80 percent of the student body. But only one out of seven members of the school board is African-American.Racial inequalities are rampant in the district: African-American students are grossly underrepresented in advanced courses and college readiness programs, but are overrepresented in special education classes and in school disciplinary matters.

The lack of adequate representation for African-Americans not only mirrors wider socioeconomic inequalities, it magnifies them by contributing to a sense of disempowerment and detachment between the Ferguson community and its government.

Part of the problem is how elections in Ferguson are structured. Members of the Ferguson-Florissant School Board are elected on an “at-large” basis from the school district as a whole, instead of from individual neighborhood voting districts (a “single-member district”) with each member representing a different neighborhood. Because voting in Ferguson is polarized along racial lines, the at-large system essentially allows the white voting majority of the school district to pick all school board members, depriving the African-American community of much of a voice on the board.

States and localities, blocked from denying African-Americans the right to vote, switched to new tactics: at-large elections, gerrymandered district lines and other arrangements that weakened the voting power of minority communities, preventing them from electing their preferred candidates.

The Voting Rights Act adapted to the times, becoming a tool to ensure not only that all Americans are able to cast a ballot, but also that their ballots are meaningful. The act prohibits local and state governments from the use of electoral schemes — such as at-large elections — that dilute the voting power of minority communities.

Which brings us back to Ferguson. On behalf of the Missouri NAACP and several African-American voters in Ferguson, the ACLU brought a lawsuit seeking an electoral system in which each school board member is elected from an individual neighborhood’s voting district. This way, our clients’ votes and voices will be heard.

If the last 50 years has taught us anything, it is that casting a vote is important — but how and where that vote is counted is equally important in the ongoing fight to give minority voters equal access to the political process.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.