While red state Republicans rail against Obamacare, the question of whether their poor constituents are eventually covered under the law’s Medicaid expansion may ultimately come down to state budget realities.

When Medicaid was signed into law as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1965, 17 years passed before the last state, Arizona, opted in. But Judy Solomon, vice president for health policy at the nonpartisan research institute Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, says the context is different this time, and that states will be won over more quickly. “I don’t think its going to take 17 years,” she says. “I hope it doesn’t take 17 years.”

Solomon thinks it’s only a matter of time before all states agree to adopt the expansion, either by accepting the plan laid forth by Obamacare or by working with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to find a different method of achieving the same end. Both Arkansas and Iowa have signed into law alternative models for using Obamacare funding to help low-income residents: Arkansas, for example, will use the money to buy private insurance for 250,000 of its residents. “The politics are such that everyone wants to put their own stamp on it,” Solomon says. “I think what we’re seeing now is that the states which will come in in 2014 or 2015 will be states with some variation on the Arkansas model or Iowa model.”

Even as the administration scrambles to get the Obamacare health care exchanges up and running, the Medicaid expansion is gaining traction. Ohio Gov. John Kasich circumvented his state’s normal legislative process Tuesday to expand Medicaid to 275,000 low-income Ohioans, citing both his responsibility as a Christian to help the poor and the expansion’s economic practicality for his state. New Hampshire legislators will meet in November with the hope of reaching bipartisan consensus on how to expand Medicaid. And Maine Gov. Paul LePage recently suggested he would be willing to work with the federal government, like Iowa and Arkansas did, to find a way to expand affordable health care options for his state’s low-income residents. Both Kasich and LePage are Republicans, and, like the New Hampshire Senate, both initially opposed the president’s signature law.

Earlier this year, Florida Gov. Rick Scott — a former health insurance executive and, initially, one of Obamacare’s staunchest opponents — went up against his state legislature to push (unsuccessfully) for using the law to help poor Floridians get insurance. Oklahoma, Indiana and Pennsylvania are considering alternative models like those passed in Arkansas and Iowa. Virginia is holding a gubernatorial election on Nov. 5 in which the frontrunner, Democrat Terry McAuliffe, has pledged not to sign a state budget that does not include the Medicaid expansion. His Republican opponent, Ken Cuccinelli, filed the first suit against Obamacare while serving as Virginia’s attorney general.

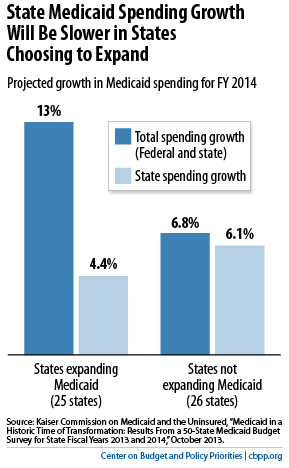

In fact, a report earlier this month by the Kaiser Family Foundation supports the budgetary arguments for the expansion advanced by many Republicans who formerly opposed the law. The study found that the 25 states that have opted in will spend less money than the states that have not. “State spending growth was slightly lower for the 25 states that are moving forward with the Medicaid expansion (4.4 percent) compared to the remaining states (6.1 percent),” the report’s authors write.

Here’s why: In 2014, Obamacare’s individual mandate will require almost all Americans to have some form of health insurance — Medicaid included — or pay a penalty. As the insurance exchanges get underway and HHS publicizes the Medicaid expansion, Americans who live below the poverty line and are already eligible for Medicaid but never applied for the benefits will apply for the first time, regardless of whether they are in a state that opted into the Medicaid expansion. So all states Medicaid rolls will see an influx of residents who live below the poverty line, a cost that will be shared with the federal government — as it currently is — with an average of 57 percent of the costs covered by the federal government and 43 percent covered by the states.

But in the 25 states that did opt in, the federal government will use Obamacare funding to cover the costs of those who were previously ineligible for Medicaid but are now eligible — that is, new enrollees who earn between 100 percent and 133 percent of the poverty line. These states will save on medical services to the uninsured for which states normally foot the bill, such as emergency room visits and mental health services. So by opting into the expansion, states will be able to insure more people for less.

These arguments could eventually change minds in big states like Texas, which at the moment is producing some of the politicians most vehemently opposed to Obamacare. “Texas is so dug in,” Solomon says, but “politics can change. I think the pressures even in a state like Texas will come from counties. The big counties there spend tons of money on indigent care.”

It was a similar push from overburdened indigent care facilities that eventually convinced the Arizona legislature to sign on to Medicaid in 1982.

It ultimately comes down to a budget decision for state governors, Solomon says. “I’m hoping that the pragmatism will trump the ideology.”