Ann Ravel in the FEC hearing room in Washington on Friday, July 17, 2015. (Photo By Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call)

Federal Elections Commissioner Ann Ravel stepped down last week, frustrated at her agency’s inability to staunch the flow of dark money in elections. On her way out the door, Ravel released a report on the problems she observed. It explains that, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, wealthy donors were using nonprofit groups — 501(c)4s and 501(c)6s — and limited liability corporations to pass money to candidates while remaining anonymous, yet the three Republican commissioners on the FEC balked at cracking down on this dark money, and on other abuses, blocking the three Democratic commissioners from taking action. When the FEC commissioners disagree along party lines, the Commission doesn’t act.

One day before she left office, we spoke with Ann Ravel about some of the incidents that bothered her most, how the situation could get worse under Trump, and the need for renewed democratic engagement in the years ahead. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

John Light: You were confirmed in 2013, when the Citizens United decision had already been around for three years. Did you expect that this would be your experience at the FEC?

Ann Ravel: I did not expect that this would be my experience. And the reason is, yes, of course, as my fellow commissioner [Republican Lee Goodman] has said, the law has changed, there has been deregulation. But there are plenty of campaign finance laws that are still in effect that are really important.

In particular, that there should be disclosure of all campaign finance information — all expenditures, all contributions. That was explicitly in Citizens United. Justice Kennedy, with the approval of eight other members of the court, said, in Citizens United, that the way that we understand whether there’s corruption is because there is robust disclosure about campaign finance information, and the internet provides that information to the public.

Well, of course, that’s not true, and that hasn’t been enforced at the FEC.

JL: In your report you lay out many examples of ways in which disclosure has not been happening the way Justice Kennedy intended. Was there a specific incident among these that made you feel like you could be more effective outside of DC?

AR: There have been numerous incidents. I’ve worked in government most of my life. I believe in government transparency, and I think that disclosure of this information is incredibly important to the public for them to believe that there’s a reason to trust government and for them to understand that the electoral process is fair. And from the beginning the commission has considered cases involving dark money through 501(c)4s, 501(c)6s and, most recently, limited liability corporations (LLCs).

One case I’ve spoken about recently was the Carolina Rising situation. The outrageous thing about Carolina Rising is that the group is a 501(c)4 tax-exempt organization. They’ve said in the past that they are a social welfare organization, even though in their disclosures to the IRS they said they were doing political activity on behalf of a Senate candidate. But even more striking was that the information showed that they had given 97 percent of their funds in order to elect a Senate candidate — 97 percent. The standard is, if a majority of their resources are used for political activity, then they should be considered to be a political committee.

The head of that 501(c)4 [Dallas Woodhouse], on the night of the election, went on television wearing his hat with the name of the candidate at the candidate’s victory party. He seemed to be slightly tipsy, and he said, “We did it.” The video is on the internet. It is outrageous. Yet the commission none the less split 3-3, and they refused to say that it’s a political committee. And the consequence of that is that if it’s not a political committee then they don’t have to disclose who their donors are. And it’s the public that does not get the information to which it is entitled.

This has been going on for quite a long time. It was obvious to me that the law was not being adhered to in a very blatant and purposeful way. There was another incident that as a human being caused me a lot of distress. And that involved the Murray energy cases that are also detailed in the report. In particular — there are two cases involving Mr. Murray — but the one that made me the most upset is that he actually shut down the coal mine in order to force his employees to have to go to a political rally for a candidate that he supported. And shutting down the coal mine meant that those hourly workers were not going to get paid for their shift. And yet, the commission did not see this as coercion, which is clearly against the law, no question about it. You cannot coerce your employees to support your political perspectives or candidates. This was a very obvious and really mean-spirited way of requiring these low-paid employees to support a political candidate, and when it was discussed at the commission, one of the [Republican] block of commissioners said, well, yeah, this was probably not good employee relations, but employee relations are not within our purview.

It was things like that that, as a human being, it impacts you greatly, because you see that not only are the decisions made at the commission part of a broader attempt to decimate the work that we do that is important in the Democratic process, they also have a more wide-ranging impacts on people.

JL: And with the Carolina Rising example — how did that discussion play out among the commissioners?

AR: Well, often, and I honestly can’t tell you precisely about what their rationale was because I haven’t looked at it recently. But often it is “this organization doesn’t exist anymore,” or “there’s no reason to do anything about this. It’s no longer in existence and therefore we can’t find anybody to penalize.”

But that actually, I think, is so disingenuous. Because whether or not the organization exists anymore, it’s important to provide this principle. Other organizations are going to set themselves up to exist only for a campaign and then they’re gone — this is often true for all these 501(c)4s and (c)6s, that they’re merely for the purpose of being political committees and then they’re gone. And so we are deprived of the ability to send a message to those organizations that there will be some consequence if they’re doing something contrary to the law. It’s the way all these organizations operate, so we’ll never be able to enforce against an organization.

JL: What harm does it do to the regular, average voter who’s trying to make a decision when we don’t know who is behind these groups?

— Former FEC Commissioner Ann Ravel

AR: The court has said that the reason that disclosure is important is twofold. One, it gives the voter all the information that they need to be able to make a reasonable decision consistent with their perspective about whether or not they want to support a candidate or an issue. So that’s the first reason. And it’s a very important reason. There have been a lot of studies that have talked about government disclosure and transparency and how important that is for assuring faith in the democratic process, and also how important it is for people to be able to use cues, voting cues, to be able to vote.

And then the other reason the court has said it’s important to have disclosure is to prevent corruption. Disclosure is a way for individuals to determine, based on the information about where people are receiving their money, if there is any corrupt activity taking place. Government officials are not equipped to investigate everything that happens. And we are dependent on having the public be a partner in making complaints. That’s true at the FEC, it’s true in California, where I worked previously. There aren’t resources to be able to investigate everything so you want people to be the watchdogs.

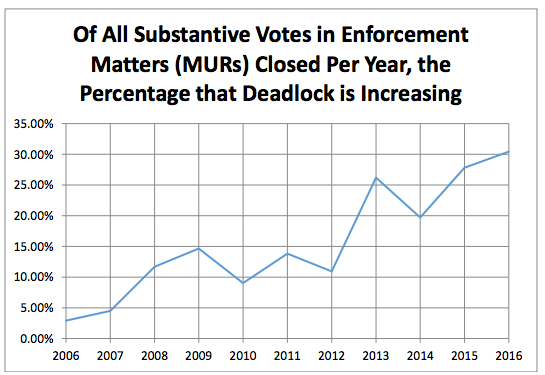

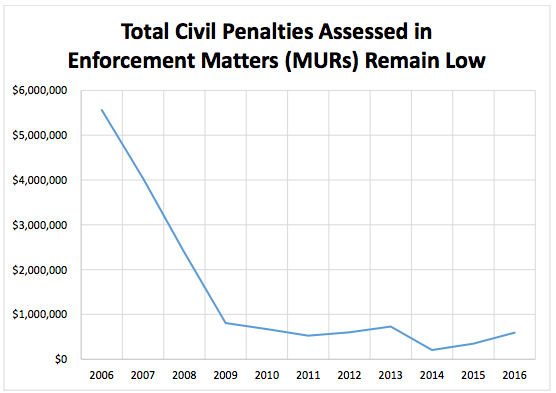

JL: In your report you make clear that the problem isn’t just Citizens United. You show real increases in deadlocked votes among commissioners, and decreases in the frequency with which the commission issues fines. It wasn’t always this way. What changed among the GOP block?

From Dysfunction and Deadlock: The Enforcement Crisis at the Federal Election Commission Reveals the Unlikelihood of Draining the Swamp, a report by former FEC Commissioner Ann Ravel’s staff.

Well, in about 2008, the GOP block turned over. It changed. Prior to that there had been vacancies on the commission. And the person who came in, together with the other two Republicans who are still on the commission, was the person who is now the White House counsel [Don McGahn]. And while I did not serve with him at any point, his impact on the commission is well known, both from what I’ve heard from commissioners who were here at the time, and others, as well as employees at the agency. It was very clear that he made a concerted effort, along with the other two Republicans, to always vote as a block. Always. And to ensure that nothing could happen.

From Dysfunction and Deadlock: The Enforcement Crisis at the Federal Election Commission Reveals the Unlikelihood of Draining the Swamp, a report by former FEC Commissioner Ann Ravel’s staff.

With regard to enforcement matters, often, the [FEC Office of General Counsel], because this is their job, recommends that there should be enforcement in certain matters. So they had taken it upon themselves to intimidate and harass the employees who were providing these neutral, nonpartisan recommendations. And that serves to, as I said, intimidate the employees at this agency, which accounts in many ways for some of the ultimate dysfunction, and it certainly accounts for the fact that we are now in the study that is done of employee morale in the federal government, at the lowest level of morale of all the small agencies in the government.

JL: And I imagine too that that must create a chilling effect on recommendations of enforcement.

AR: Yes, absolutely it does. In addition, since I have been here, we have not had a general counsel because there is a stalemate, and these commissioners do not want anybody who is going to be an enforcement lawyer. They want people who are going to do nothing.

JL: It strikes me that the FEC, before many other agencies, had the experience of being led by folks who are ideologically opposed to its mission, and now we’re seeing that more with other agencies in Washington.

AR: You’re quite right. The way I see it, the FEC was in a way a test case. It was an important commission that had an impact on members of Congress and senators and their campaigns. And Sen. McConnell, who appointed all three of these commissioners, has a strong ideological opposition to disclosure and campaign finance law. So the effort to decimate this commission was done tactically and thoughtfully and now it’s something that will ultimately be utilized for many other agencies in the government. The idea of public service, and following what the missions of the agencies are, is not something that seems to be of concern.

JL: As you mentioned, Don McGahn is now the White House counsel. What should we make of that?

AR: The concern about that is that he is a person that once said about the FEC, “I’m not enforcing the law as Congress passed it. I plead guilty as charged.” And that is a stunning thing for any lawyer to say. But it is also stunning for any person who is supposedly doing the service to the public that they were appointed to do and expected to do when they were confirmed by the Senate. So I think what we can make of that is that the advice that he’s going to give may not be the kind of advice that most general counsels should, which is neutral, thoughtful, helping the president achieve whatever the president’s policy desires are but also giving very careful explanations of legal concerns.

JL: I can imagine folks who agree with you saying, ‘You have the right perspective on this. Why let the administration replace you?’ What would your response be to that?

AR: I have two months left on my term. The other commissioners, all five of them, are already holdovers. The president can replace everybody. And one person on the commission has no ability to accomplish anything. In fact, three of us have no ability to accomplish anything, nor have we been able to. Because it requires four votes to do anything. It’s likely that the president will make replacement appointments because it’s rumored that some of the Republican commissioners would like to go to the administration.

But 3-2 or 3-3 — it’s the same. It means that nothing will happen. And that’s what they [the Republican commissioners] want to achieve. What we want to achieve is to affirmatively write regulations on the impact of foreign money in our campaigns. We want to do enforcement of those who are violating our laws. But it requires four votes. I am very gratified that there are people emailing me saying I have to stay for the good of the country. But actually, for the good of the country, I think I can do better on the outside.

JL: You’re saying that some of the GOP commissioners want to move into the administration. Do you think that now, with an entire commission where everyone’s terms are expired, we may see a full slate of six new appointments?

AR: I have no way of knowing. I think probably a couple of the commissioners who are here now will probably stay, one from each party. The tradition has been that a Republican has been paired with a Democratic nominee. So my guess is that probably there will be either four new appointees or what’s also possible is that the president will do removals and appointments in a way that will ensure that there is not a quorum so that really nothing can happen. These are the two alternatives that I see.

JL: What would you urge people to do to challenge this trend during the Trump administration?

AR: I believe the Congress may yet be an avenue for change at the FEC. Not that — I never thought that the composition, 3-3, should be changed. Clearly, there are other reasons why elected officials in the Senate and Congress would not want there to be a tiebreaker that is of one party or another. But what is so important is that there be people who come to the table with good faith and a belief in the law. I think that — this may sound naive — but I do think that it would make sense for people to put some pressure on their senators and their congresspeople to make sure that something happens in that regard. So I’m always in favor of mobilization of some kind to keep this issue at the forefront, which is why I’ve tried to be so public about it.

JL: Would you be able to comment on what the FEC’s role should be with the president suggesting that millions of people voted illegally? I’ve seen that one of your fellow commissioners was speaking out about that.

AR: Well, I do think that our job is to insure fairness in the electoral process. And we have an important role in democracy and insuring faith and trust in democracy, and allowing and working to permit more people to participate in the political process, all within the ambit and the scope of our role. So, for example — I’ve been roundly criticized for this — but for many years I’ve talked about the role of campaign finance in making it difficult for women, minorities and people of modest means to run for office. So while that is not specifically within our purview — we don’t rule on those issues, obviously — they’re so closely related to what we do that it makes sense for us to speak out on those issues. So obviously the commissioner who spoke about those issues is being criticized, and complaints are being filed, but I do think that our job in this government agency is to uphold our democratic values.

JL: What do you have planned next?

AR: While I’m working for the government I haven’t been able to make final plans with anybody, although it was reported by The Washington Post that I’ll be a professor at [University of California, Berkeley] law school — I’m teaching one class, on ethics, in fact. But I am talking to a number of different foundations and other groups both internationally and in the United States to continue to work in the area of campaign finance and democracy issues. My real kind of focus is on civic engagement. I think one of the real effects of not just our campaign finance system but economics and other reasons is that people are disengaged. People do not feel a connection to government or to the political process. I find that concerning.

[Economist] Joseph Stiglitz has talked about this, and I find it very convincing: When people lose faith in government they became disengaged and disassociated and we are going to have, essentially, a permanent class of outsiders who don’t feel connected to our country or to our community mores. I am concerned that this political system has sidelined people and people feel they don’t have a voice. I want to work, and work in communities, to see what can be done to help people to feel more involved.