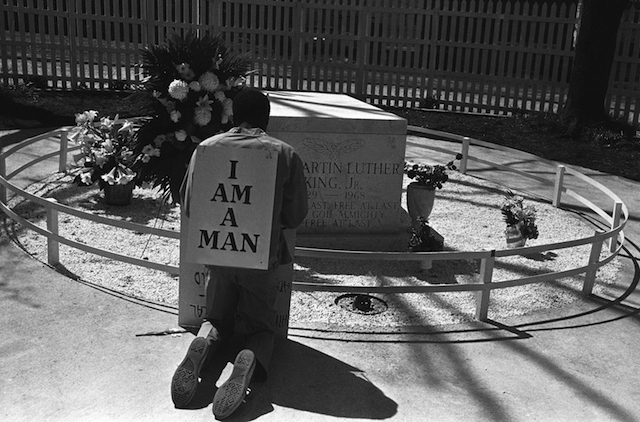

A striking Atlanta sanitation worker kneels at the grave of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after a rally by Southern Christian Leadership Conference supporting the strike in Atlanta on April 4, 1970. King was killed in Memphis while supporting a sanitation workers’ strike there in 1968. The picket signs reading “I Am A Man” were first used in the Memphis strike. (AP Photo/BJ)

Can American history teach us anything about how to eradicate economic inequality? It can and what it tells us is not reassuring. Historically, American reform occurs sporadically, lasts briefly, and brings about only incremental changes. It took the Great Depression to create the opportunity to only partially fix the excesses of American capitalism. And historians have long argued that it was not FDR’s New Deal which ended large-scale unemployment but World War II.

Perhaps the most revolutionary effort to end American inequality occurred almost 50 years ago and was led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The urban riots that occurred between 1964 and 1967 in New York, Boston, Los Angeles, Cincinnati, and, worst of all, in Newark, New Jersey, where 44 people died, convinced King that his movement had done little to improve the lives of those trapped in American ghettos. Even before the 1967 Newark tragedy, he decided to dedicate his life to the elimination of poverty. “I choose to identify with the poor,” he told his congregation in August, 1966. “.. If it means dying for them, I’m going that way, because I heard a voice saying, ‘Do something for others.’” Those words summed up the last two years of his life.

He could not have chosen a worse time to mount a “Poor People’s Campaign.” The Vietnam War had torn the Democratic Party apart, breaking its reform coalition. On April 4, 1967, King officially joined the anti-war movement.

Speaking at New York’s Riverside Church, he publicly denounced the Vietnam War with a passion he’d once expressed for voting rights. “The greatest purveyor of violence in the world today,” he said, was the United States. To save itself, America must lead an international crusade against “poverty, racism, and militarism.”

Vietnam and the ghetto riots radicalized King. “For years I labored with the idea of reforming the existing institutions of the South, a little change here, a little change there,” he told the journalist David Halberstam in April 1967. “Now I feel quite differently. I think you’ve got to have a reconstruction of the entire society, a revolution of values.” Such a reconstruction, he explained, entailed many of the characteristics long associated with Socialism, such as a “multibillion dollar Marshall Plan” for the cities, a guaranteed national income for the poor and government control of major industries.

In October 1967 he announced that he would soon launch a “Poor People’s Campaign,” a march on Washington, where the impoverished of all races would set up shelters on the Washington Mall and “cripple the operations of a repressive society” until the federal government granted them an “Economic Bill of Rights.” Such an effort included “nonviolent sabotage,” poor people “lying on highways, blocking doors at government offices, and mass school boycotts.” Such “militant tactics,” King believed, were as “dramatic, as dislocative, as disruptive, as attention-getting as the riots without destroying property.” To a skeptical staff, he said, “We’ve got to go for broke this time…If necessary I’m going to stay in jail six months. They aren’t going to run me out of Washington.”

LBJ, fearing that King’s plans would wreck his re-election, begged him to call off the campaign. J. Edgar Hoover told the president that King had now become “an instrument in the hands of subversive forces seeking to undermine our nation,” and launched POCAM, a major Bureau effort to destroy the Poor People’s Campaign.

King refused Johnson’s request and ignored the increased FBI surveillance as well as reports of impending assassination attempts, which grew daily. He toured to raise money while his emissaries visited more than half a dozen cities that had experienced rioting. They hoped to persuade the poorest people to join their cause. But from the first, the campaign faltered. The money wasn’t there, siphoned off by people already contributing to the anti-war movement. Nor did the urban poor wish to travel to Washington, where they would live in tent cities until the government came to their rescue. King had hoped to recreate Birmingham and Selma: organize the masses, demonstrate, touch the conscience of the nation, and thus force the government to act. It had happened in 1963 and 1965, so surely it could happen again.

But it didn’t. “We’re in terrible shape with this campaign,” King told an aide. “It just isn’t working. People aren’t responding.” But his plans to occupy the capital went forward.

King’s closest friends grew increasingly worried about his physical and emotional health. He was smoking and eating too much, sleeping too little and suffering daily from migraine headaches. Sometimes he broke into tears during public events.

Only one thing might lift King’s spirits: a call for help. It came in March 1968 from his old friend Jim Lawson now leading a campaign to improve the lives of Memphis’ sanitation workers. Again, his staff opposed his involvement but King saw it as preparation for struggle in Washington and flew to Memphis. It was there that an assassin took his life on April 4, 1968.

Ralph Abernathy, King’s chosen successor to head the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, went forward with the Poor People’s Campaign. On May 12, 1968, Coretta Scott King brought 5,000 demonstrators to Washington, DC, seeking an Economic Bill of Rights. “Resurrection City,” a shantytown, was constructed on the Mall to house many of the visitors who met with congressman and senators to plead their case. None of the disruptive activities envisioned by King occurred, and people quickly began leaving the city before the National Park Service’s permit to camp expired on June 23.

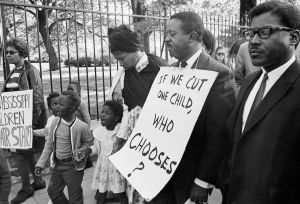

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who succeeded the slain Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, joined a group of Mississippi protesters on April 25, 1968 in front of the White House. The picketers were protesting any slash in funds needed for the Head Start Program. (AP Photo/ Bob Schutz)

The next day, over a thousand police attempted to clear Resurrection City and several hundred demonstrators were arrested, including Ralph Abernathy. There was sporadic violence and the National Guard was activated to restore order. No Economic Bill of Rights was ever created and the campaign produced only minimal results — more food stamps became available and funding for Head Start programs in Mississippi and Alabama was increased. One SCLC official called the Poor People’s Campaign their “Little Bighorn.”

Had King lived, it is doubtful that he could have achieved more. The American political system is incapable of producing the massive changes King prescribed in 1968 and other groups like #BlackLivesMatter are recommending today. That such changes are needed is indisputable but how to achieve them in a time of institutional and political paralysis is the million dollar question that lacks a practical answer. That 20 children and six adults could be slaughtered at Connecticut’s Sandy Hook Elementary School in December, 2012, without producing any reform of gun laws seems to foreclose the possibility that any campaign to eliminate economic inequality could possibly succeed. The unfortunate history of the Poor People’s Campaign and the failure to deal with contemporary outrages is not a prescription for inaction, however. Quite the contrary.

King put it best: “I can’t lose hope,” he once said, “because when you lose hope, you die.”