This post first appeared in The Nation.

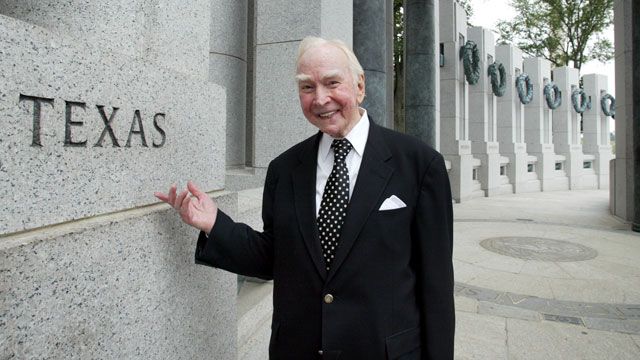

Former Speaker of the House Jim Wright has voted in every election since 1944 and represented Texas in Congress for 34 years. But when he went to his local Department of Public Safety office to obtain the new voter ID required to vote – which he never needed in any previous election – the 90-year-old Wright was denied. His driver’s license is expired and his Texas Christian University faculty ID is not accepted as a valid form of voter ID.

To be able to vote in Texas, including in Tuesday’s election for statewide constitutional amendments, Wright’s assistant will have to get a certified copy of his birth certificate, which costs $22. According to the state of Texas, 600,000 to 800,000 registered voters in Texas don’t have a valid form of government-issued photo ID. Wright is evidently one of them. But unlike Wright, most of these voters will not have an assistant or the political connections of a former speaker of the house to help them obtain a birth certificate to prove their identify, nor can they necessarily make two trips to the DMV office or afford a birth certificate.

The devil is in the details when it comes to voter ID. And the rollout of the new law in Texas is off to a very bad start. “I earnestly hope these unduly stringent requirements on voters won’t dramatically reduce the number of people who vote,” Wright told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “I think they will reduce the number to some extent.”

As I’ve reported previously, getting the necessary voter ID in Texas, which has one of the strictest laws in the country, is no walk in the park. As in Wright’s case, you need to pay for a birth certificate or another type of citizenship document to obtain one (which Eric Holder called a poll tax). A handgun permit is an acceptable voter ID in Texas but a university ID is not. And there are no DMV offices in 81 of 254 counties in Texas. That’s probably why only 50 of the 600-800,000 registered voters without voter ID in the state have so far successfully obtained one. (The Department of Justice has filed suit to block the law, which was invalidated by a federal court last year but reinstated when the Supreme Court invalidated Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act. Texas filed a motion last Friday to dismiss the lawsuit.)

Beyond the hundreds of thousands of voters, like Wright, who don’t have valid ID, millions more in Texas could be inconvenienced or disenfranchised by a provision of the law stipulating that a voter’s photo ID be “substantially similar” to their name in the poll book. In this year’s elections for statewide constitutional amendments in Texas, a district court judge, a state senator and both candidates for governor — Wendy Davis and Greg Abbott — had to sign affidavits to vote because their IDs didn’t match their poll book names.

In a highly ironic twist, Davis, a critic of the voter-ID law, offered an amendment to allow voters whose IDs were not identical to their poll names to be able to sign an affidavit to vote, which allowed her 2014 gubernatorial opponent, Greg Abbott, a top supporter of voter ID, to cast a ballot this year.

Reported Zack Roth of MSNBC:

In 2011, Davis introduced an amendment to the voter-ID bill saying that if names are substantially similar but not identical, voters can sign an affidavit and still vote. The original bill as drafted by Republicans would have required voters in that situation to present a document showing a name change — something few people bring with them when they go to vote.

And it gets better — or worse. Greg Abbott, the front-runner for the GOP nomination for governor, also will have to sign an affidavit, his campaign said, thanks to a similar names mismatch. Abbott, the state attorney general, has defended the voter-ID law in court.

“If it weren’t for Wendy Davis’ leadership, Greg Abbott might have nearly disenfranchised himself,” Davis spokesman Bo Delp said.

One in seven voters in Dallas County has had to sign an affidavit in order to vote this year. That’s over 1,000 voters so far. This requirement can create a lot of confusion and, at the very least, makes voting take longer than it should. In a high turnout election, like in 2014 when Davis will face Abbott, Texas could very well resemble Florida when it comes to long lines and electoral dysfunction. “When you have a huge turnout, a minute for every voter could really produce some lines,” Dallas County elections administrator Toni Pippins-Poole told the Dallas Morning News.

Supporters of voter ID, like Abbott, claim the law is necessary to stop voter fraud, even though there’s been only one voter impersonation conviction in Texas since 2000. Instead, the law is ensnaring the top political leaders in the state. And this is only the beginning, unless and until the federal courts decide to stop it.