Under Trump’s plan, the official tax rate for banks would drop to 15 percent, and they’d still benefit from loopholes that would let them pay even lower rates. (Photo by Michael Fleshman/ Flickr CC 2.0)

This post originally appeared on Mother Jones.

In 1980 the federal deficit was soaring and Ronald Reagan campaigned on a singular promise: He planned to cut taxes on everyone, but especially the rich. He insisted that those benefits would quickly trickle down to everyone and supercharge the economy. Throw in some social safety net cuts, Republicans said, and the whole plan would pay for itself.

They were wrong. The rich got lower taxes all right, but the economy flatlined and the deficit skyrocketed. I should know: I graduated from college the same summer the tax cut passed, and I spent the next three years managing a Radio Shack waiting for the economy to get back on its feet. In 1982 Reagan was forced to raise taxes to make up for his cuts, and he continued raising them throughout his presidency.

In 1993 Bill Clinton passed a tax increase to reduce the deficit. Republicans insisted it would do no such thing. In fact, they said, it would cripple the economy.

They were wrong. The economy boomed, and for the first time since the Roaring ’20s the deficit turned into a surplus for four consecutive years.

In 2001—and again in 2003—George W. Bush passed a tax cut. Once again, Republicans said it would supercharge the economy and pay for itself.

They were wrong. All we got was a jobless recovery and a housing bubble that wrecked the economy. It produced the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

At the beginning of 2013, as part of the “fiscal cliff” negotiations, Barack Obama forced Republicans to accept a tax increase on high earners. But even though the bill passed with bipartisan support, some Republicans insisted it would kill the economy.

They were wrong. The deficit declined and Obama produced the longest economic recovery in American history—one that was still going strong until the coronavirus pandemic killed it.

Finally, in 2017, Republicans passed yet another tax cut. This one primarily benefited corporations and the rich, and once again Republicans insisted it would supercharge the economy and pay for itself.

They were wrong. No—scratch that. They lied. They knew the evidence of the past 40 years as well as anyone, but they sold the public a bill of goods anyway.

Every single economic indicator Republicans said would go up, didn’t.

Why? Because for all of Donald Trump’s bluster, this was the one thing he really, truly had to do. It’s the one thing the Republican Party’s big donors insist on. They don’t care about immigration or tariffs. Not much, anyway. But they care about lower taxes. As then-New York Rep. Chris Collins (since convicted of insider trading) told reporters shortly before the tax cut was signed into law, donors were telling him, “Get it done or don’t ever call me again.” So they got it done.

The 2017 tax cut had to be supported by a farrago of dishonesty for an obvious reason: The public would never support a tax cut aimed primarily at making the rich richer and swelling the coffers of large corporations—which also benefited the rich. Why would they? So Republicans had to lie. And this time they couldn’t rest with a single lie. Polls showed that voters were skeptical of their tax cut, so this time Republicans had to pile lie on top of lie.

Why does this matter? For two reasons—one, lies about tax cuts have determined the course of America’s economy, and the individual fortunes of millions of families including yours, for decades. Many of the inequities laid bare by the pandemic have been in the making since the Reagan era. And two, amid the coronavirus crisis, we’re about to have another debate over whether tax cuts can juice the economy. To evaluate those claims, it behooves us to look at what Republicans said about their 2017 tax cut—compared to what actually happened. Spoiler alert: Every single economic indicator Republicans said would go up, didn’t.

It all started with the initial justification for the tax cut: namely that American corporations paid the highest tax rates in the industrialized world, which put them at a huge competitive disadvantage. So at the end of 2017, while they still had full control of Congress, Republicans passed a $1.5 trillion tax cut—nearly the size of the gigantic coronavirus rescue bill passed in March. The 2017 bill contained cuts to both the personal tax rate—which mostly benefited the rich—and the corporate rate. But Republicans faced a cognitive dissonance problem: Weren’t American corporations actually doing pretty well? Why did they need a huge handout?

This is where the first lie came into play. It’s true that the United States had a high corporate tax rate, but few American corporations paid that official rate. In fact, if you look at actual corporate tax revenue, it turns out the United States has been pretty friendly toward big business. The real corporate tax rate is middling, and among the 20 richest developed countries, the US tied for dead last in how much of its GDP comes from such taxes.

This was no secret. So to justify cutting corporate tax rates even further, Republicans had to manufacture a laundry list of reasons it would be good for the economy. And that’s when the lies started piling up.

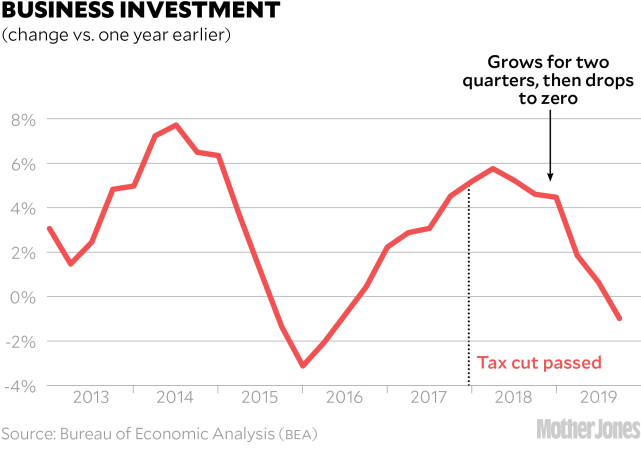

1. Business investment will skyrocket

The first and most fundamental logic behind the Republican predictions that a corporate tax cut would promote economic growth and higher tax revenues was a simple one. According to the academic language in a paper published by the White House Council of Economic Advisers, “A decrease in the tax rate on corporate profits…decreases the before-tax rate of return used to assess the profitability of an investment project.”

In plain English this means that corporations will only make investments that are likely to be profitable. Taxes are part of this, so if you decrease the tax rate on profits, more investments will go forward. In the words of Larry Kudlow, the lifelong supply-sider who became director of President Trump’s National Economic Council, corporate tax cuts produce an “investment boom.”

But Kudlow’s boom never came. Taxes may matter, but what matters a lot more is whether corporations have confidence that the economy will grow vigorously and produce more demand for their products and services. The Republican tax cut didn’t produce that confidence. Regardless of what they said in public, most CEOs knew perfectly well that a tax cut was just a temporary shot in the arm. It might modestly spur consumer demand for a short time, but in the long run it would do nothing—or maybe even produce a weaker economy.

Sure enough, business investment, which usually reflects decisions made in the past, grew on autopilot for a couple of quarters, but after that, steadily declined. In the last quarter of 2019, the level of business investment was lower than it was a year before.

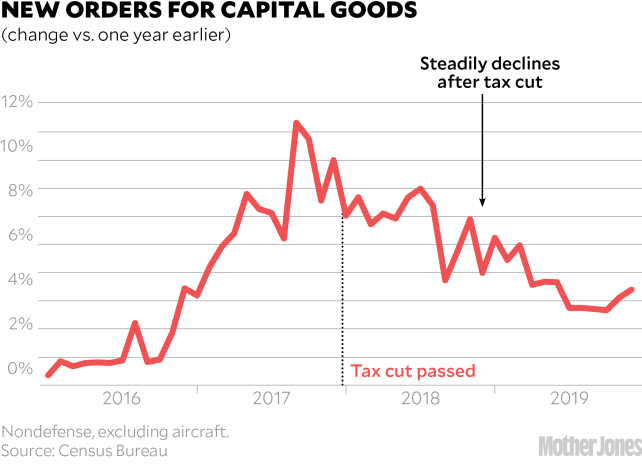

You can also look at new orders for capital goods, which generally react quickly to changes in the economic outlook. But the growth rate of new orders began declining immediately after the tax cut was passed, reaching zero in late 2018 and falling into negative territory in mid-2019. (Charts are adjusted for inflation where relevant and run through the end of 2019, before the COVID-19 recession took hold.)

It’s been more than two years since the tax cut passed, and if an investment boom were going to happen, we would have seen it by now. We haven’t. Trump may like to brag about the “greatest economy in history” that he claims he built before the pandemic struck, but all we saw was an investment bust.

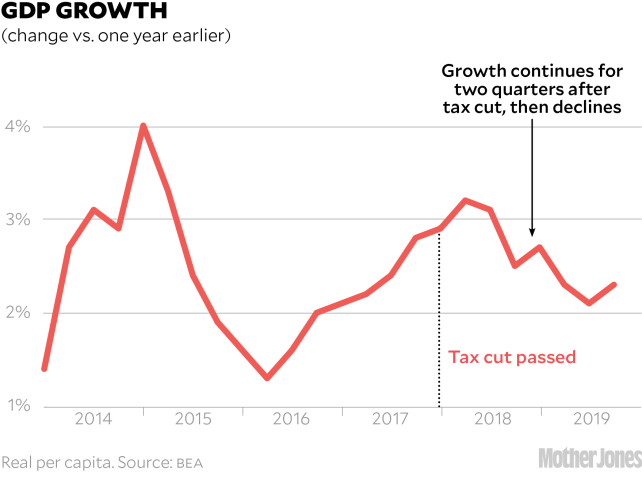

If an investment boom was the big lie that drove everything, the arguments made to the general public in support of the tax cut mostly revolved around a better-known metric: economic growth. The usual way of measuring this is by looking at gross domestic product, the sum of all goods and services produced in the United States. In the decade since the end of the Great Recession, GDP growth has averaged 2.3 percent per year.

Republicans claimed that the investment growth spurred by the tax cut would drive GDP growth higher. Kudlow predicted growth rates of 3 to 4 percent. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin went with a more modest 2.9 percent. Trump himself told reporters at his Cabinet meeting that he was holding out for 6 percent growth. These projections were mostly just spun out of thin air.

So how did we do? Since the investment boom never materialized, it’s hardly a shock to learn that GDP growth didn’t boom either. The growth rate increased modestly for two quarters and then dropped steadily. In the last quarter unaffected by the coronavirus crisis, it was barely above 2 percent. Not only didn’t the tax cut usher in the growth that Republicans predicted, but growth rates started dropping soon after.

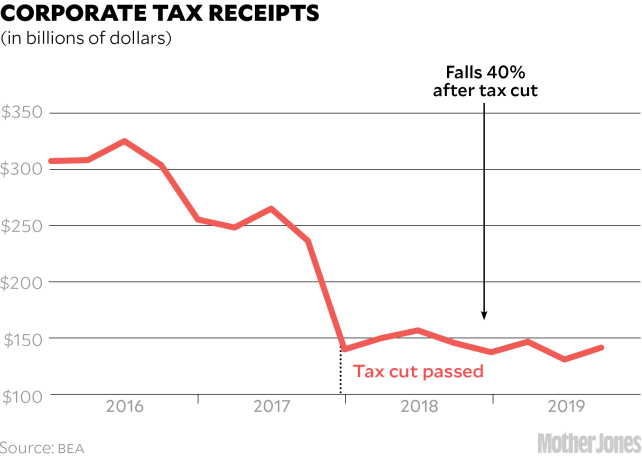

3. The tax cut will pay for itself

It was an article of faith among Republicans that their tax cut wouldn’t just boost economic growth, but would actually generate more revenue than the old, higher tax rates. “Not only will this tax plan pay for itself, but it will pay down debt,” Mnuchin said. Kevin Hassett, then chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, agreed: “You don’t really need to have a big growth effect to have Secretary Mnuchin be correct.” Former Rep. Jeb Hensarling, chair of the House Financial Services Committee, insisted that economic growth would be “more than enough” to make up for the lower tax rates.

That growth failed to materialize. Unsurprisingly, so have higher tax revenues. Corporate tax receipts plummeted from $240 billion to $140 billion in the first quarter after the tax cut passed, and have stayed at that level ever since.

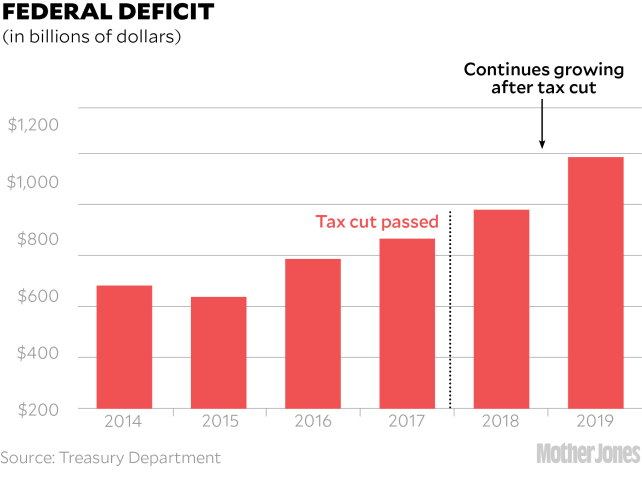

So what happened to the federal deficit? Republicans lied about the effect of their cut on tax receipts and at the same time they also decided to stop worrying about keeping spending down. As a result, the federal deficit has gone up—and that’s not even accounting for the COVID-19 stimulus spending. This comes as no surprise to anyone who has heard the same Republican tax arguments for decades and now recognizes them for the fabrications they are.

4. Corporations will bring back profits stashed overseas

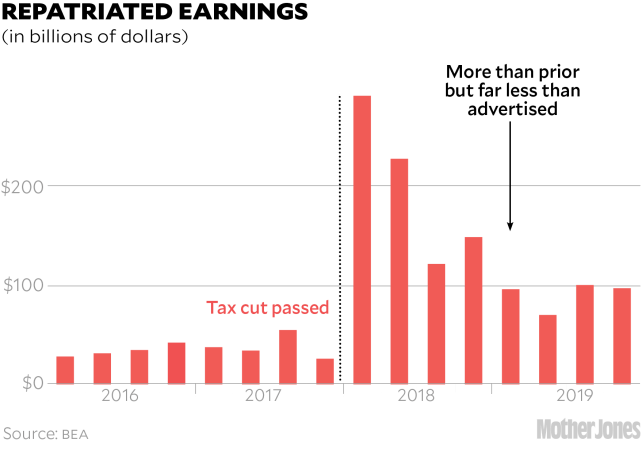

Republicans did their best to include as many corporate giveaways as possible in their tax cut, but spun them as a benefit to the greater economy. Take “repatriated earnings.” American multinational corporations like to keep their overseas profits away from the IRS, and the Republican tax plan aimed to change this by offering companies a temporary “tax holiday.” Earnings kept overseas would be subject to a one-time tax at a very low rate that could be paid over the course of eight years. President Trump promised that this would produce a flood of repatriated earnings amounting to $4–$5 trillion—nearly twice the amount that corporations were actually storing overseas.

This was just another lie, one that no serious economist believed for a moment. And indeed, after a brief boom in repatriated earnings after the tax cut passed, there was a bust. Repatriations to date have amounted to only $840 billion above normal, and the total amount of repatriations in the last quarter of 2019 is only $60 billion higher than it was before the tax cut passed. The total will never come anywhere close to $4–$5 trillion.

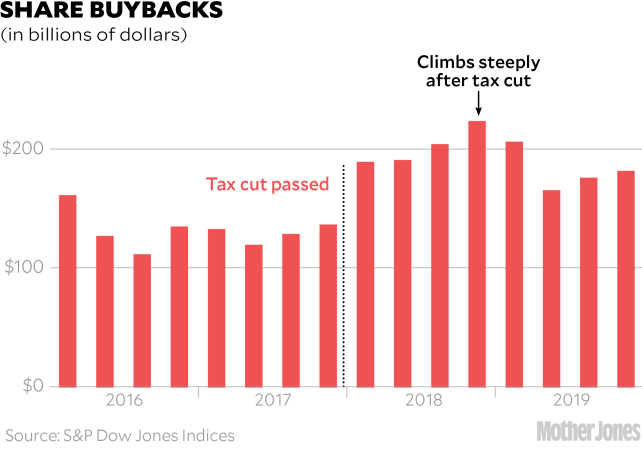

Why does this matter? The Republican theory was that companies would use their repatriated earnings to invest in new capacity, which in turn would boost the economy. This was an unusually feeble lie since American companies were already sitting on huge stockpiles of cash that they could have spent if they wanted to. The four biggest US tech companies alone—Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft—had more than $340 billion in cash on their books. But companies don’t invest simply because they have spare money lying around; they only invest if they think the economy is going to grow. If they don’t believe that, they’ll take the extra cash and return it instead to stockholders—i.e., the rich. And that’s exactly what they’ve done.

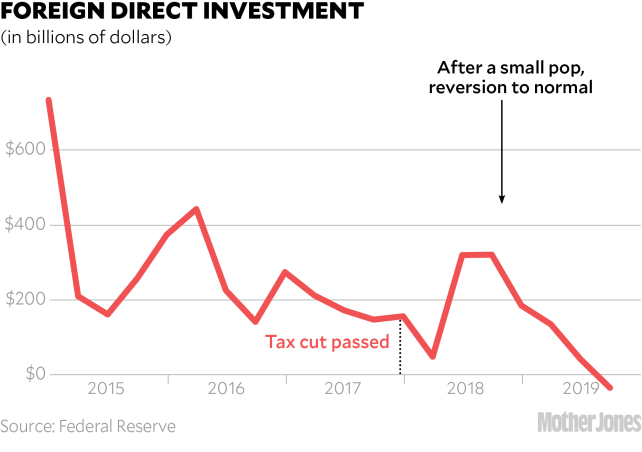

But maybe foreign investors responded more positively to the tax cut than domestic investors did? Nope. Foreign investment increased briefly but then plunged. Apparently they didn’t take Republican promises any more seriously than Americans did.

5. Your wages will skyrocket

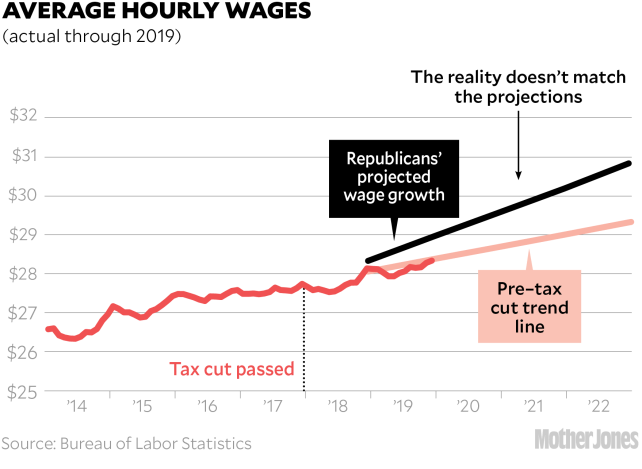

If all this weren’t enraging enough, just wait. You see, the White House also promised something else: that the wages of ordinary workers like you would go up. How much? The claims were all over the map. In a single CEA paper, administration economists predicted that average incomes would rise at least $3,000 and perhaps as much as $9,000 after the tax changes had been “fully absorbed by the economy.” This was on top of the normal income growth already baked into economic forecasts. So what actually happened?

Well, not only are we nowhere near the White House projections, we’re actually still on the trend that was predicted without the tax cut. The Republican tax cut did your wages no good at all.

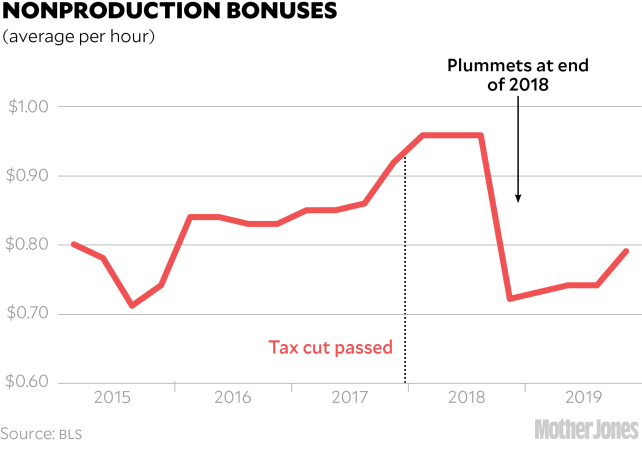

But wait. What about bonuses? Lots of companies promised they’d pay out extra bonuses if the tax cut passed. AT&T promised $1,000 per employee. Comcast followed suit and Southwest and American Airlines joined in too. Walmart was less generous: It also announced a $1,000 bonus, but only for workers who’d been with the company for at least 20 years.

It made for great headlines. But once the klieg lights were off, bonuses nose-dived to less than they had been before the tax cut.

In the end, the Republican tax cut didn’t help your wages and it reduced your bonus. Are you mad yet?

6. Jobs, jobs, jobs!

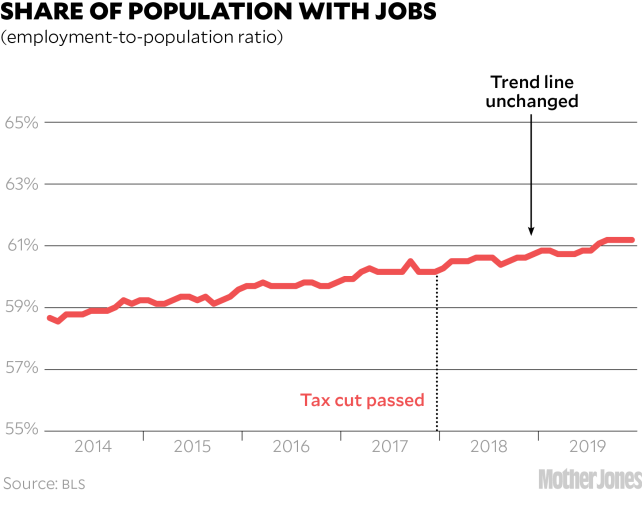

Mnuchin declared that the Republican tax bill would be a boon for employment. “This is about jobs,” he said. “This is a jobs bill.”

But it wasn’t. If you look at the total share of the country with jobs—the “employment-to-population ratio”—nothing happened after the tax cut passed. It had been growing since the end of the Great Recession and it continued growing at the exact same rate after the tax cut was passed, until COVID-19 hit.

7. Tax cuts for all

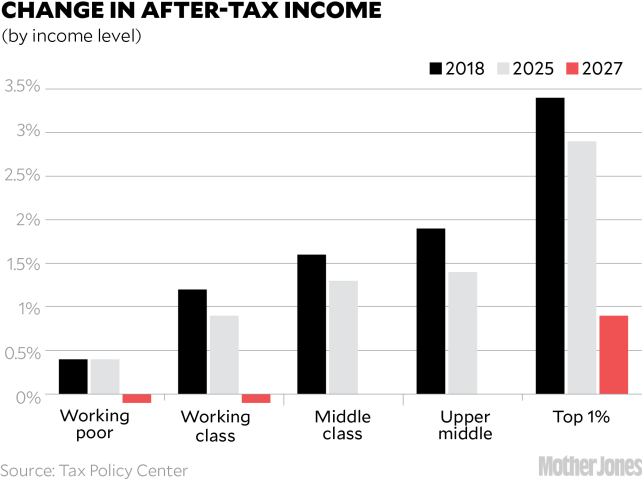

Of course, the Republican tax act did more than just reduce the corporate tax rate. It also reduced individual income taxes for nearly everyone—partly by cutting tax rates and partly by adding a hodgepodge of other benefits. But for most of us, there’s less there than meets the eye.

In 2018, nearly everyone got a tax break, and after-tax incomes went up—although the income of the rich went up a lot more than the income of the middle class. By 2025, the tax break for the middle class will start to vanish. And by 2027, the reduction in income tax rates will disappear for everyone. However, the rich—and only the rich—will continue to benefit from other tax breaks.

Republicans claimed that ending the rate cuts in 2027 was nothing more than an accounting requirement to meet congressional budget rules. They’ll restore it later. But this is just a con job. If they were really sure they could eliminate tax cuts and restore them later, why not zero out their patchwork of tax cuts for the rich? The question answers itself.

8. But guess what? Corporate profits soared

To summarize: The economy didn’t boom, investment didn’t increase, employment didn’t go up, household earnings didn’t surge, and the middle-class tax cuts started out small and then disappeared completely. But there’s one thing that has worked—besides tax cuts for the rich, that is: corporate profits have fattened nicely. Check that out. Corporate profits jumped 8 percent immediately after the tax cut was passed, and they’ve stayed at their new, higher level ever since. It all goes to show that Republicans can accomplish their goals when they put their mind to it. You just have to know what their goals really are.

Now it’s time for a look into the near future. But first let’s zoom out a bit because there’s more to this than just tax cuts for the rich. Republicans have long been devoted to a strategy called “starve the beast,” which has a simple goal: (a) cut taxes, (b) watch revenues fall, and (c) insist that spending has to be cut to avoid big budget deficits. And while the rich may get the tax cuts, the spending cuts are inevitably aimed at the poor and middle class. This is especially effective at the state level because most states aren’t allowed to run budget deficits. If tax revenues fall, they have to cut spending.

And now we have to deal with a pandemic. If the holes in our eroding social safety net seemed patchable before, they don’t any longer. Unemployment insurance? Democrats did a good job of demanding a temporary funding increase, but not everyone benefits because many states have spent years deliberately making their systems hard to use and they’re unable to hold up under hundreds of thousands of new applicants.

When economists say “stimulus,” Republicans hear “tax cut.”

Food stamps? Republicans are trying to cut them back just as we need them more than ever. Medicaid? The federal government can still afford to pay its share, but can states? Their tax revenues have plummeted and Republicans have balked at helping them out.

Thanks to the pandemic, we’re about to get hammered by the business end of the starve-the-beast strategy. Tax revenues have already declined due to the Republican tax cut, and they’ll decline more because Republicans used the coronavirus rescue bills to quietly “fix” a few problems in their 2017 bill that turned out to be annoying to the rich. Beyond that, spending has exploded as the rescue bills create trillions in temporary new outlays to help people and businesses brought to their knees by lockdowns and closures. This is going to cause a massive increase in the federal deficit, and Republicans are already making noises about suddenly becoming deficit hawks again. In fact, within minutes of passing the April coronavirus bill, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was warning that “we can’t borrow enough money to solve the problem indefinitely.”

But even though Republicans may wish they could stop further rescue packages, as we come to grips with the scale of the wreckage, there will be demands for more. Epidemiologists think it’s likely we’ll have another surge of coronavirus cases in the fall, and that will produce more calls for large, broad-based stimulus bills to keep the economy afloat.

When economists say “stimulus,” Republicans hear “tax cut.” As it happens, there are actually good reasons to include certain kinds of tax cuts—those that help middle- and working-class people—in any stimulus package. They can be implemented quickly; they can be made as large as necessary; they put money directly in consumers’ pockets; and they can even be targeted to a certain degree, helping those who have suffered the biggest losses from the pandemic.

But they can also be targeted toward the rich. And that’s what Republicans are certain to propose. So here are some alternatives that Democrats would be well advised to look at.

The most obvious candidate is the Social Security payroll tax. You pay a flat tax of 6.2 percent—which makes it regressive to begin with—and it applies only to your first $137,700 of income. Everything above that is tax free, which is why millionaires pay an effective rate of less than 1 percent.

Suppose you reduce the worker’s share of the payroll tax by two percentage points. This barely affects the rich: A millionaire’s effective rate goes down from 0.9 percent to 0.6 percent. But everyone with less than $137,700 in income sees their rate go down from 6.2 percent to 4.2 percent. The nonrich benefit considerably while the rich barely even notice anything has happened.

But there’s a catch: Payroll tax cuts do nothing for you if you’re unemployed, or you’ve been laid off, or you’re paid under the table. This is why Democrats fought against a payroll tax cut in the first round of coronavirus rescue packages. But even more importantly, the payroll taxes fund Social Security, and if you reduce them, Social Security will be even more underfunded than it is now. The answer is to make sure that any loss of payroll tax revenue to Social Security is made good by infusions from the general fund. These would need to last as long as the stimulus bill is active.

Another candidate is an increase in tax credits. Unlike a deduction, tax credits are subtracted from your taxes owed. The higher the credit, the lower your taxes. Current examples include the child tax credit and the Earned Income Tax Credit.

Increasing credits is an attractive way to juice the economy because they often have fixed maximum amounts. If you lower the taxes of a millionaire by, say, $3,000, it’s a drop in the ocean. But for a middle-class family it’s real money. Democrats could propose increases in existing tax credits, or just a brand-new “pandemic tax credit.” Either way, it could cut taxes without shoveling money into the wallets of the rich.

Another subtler form of taxation that Democrats could target is tax expenditures. A tax expenditure is a deduction, exemption, or exclusion targeted at a specific activity. The most famous is the mortgage interest deduction, which is a straight-up subsidy to homeowners, but one that’s hidden in the tax system. There are more than 100 different expenditures adding up to well over $1 trillion—more than the revenue from Social Security taxes, corporate taxes, or excise taxes. (And not much less than we get from federal income taxes.)

Tax expenditures tend to favor the rich. For example, a middle-class homeowner might pay a 12 percent income tax rate and own a modest home that nets a deduction of $5,000. That’s a tax reduction of $600. And if they don’t have other expenditures to itemize, they might not get a reduction at all.

But a rich homeowner might pay an income tax rate of 37 percent and own an expensive home that nets a deduction of $50,000. That’s a tax reduction of $18,500.

If it’s a tax cut fight they want, Democrats can come armed with a slate of their own options.

The easiest way to make this fairer is to cap the amount of the deduction—as, in fact, we do with the mortgage interest deduction. But the better bet is to increase the deduction for nonrich families. Maybe we could just double the deduction for anyone with an income under $100,000. That would cut their taxes without also giving a windfall to the rich.

Finally, there’s another class of taxes entirely: state and local taxes. The sales tax is the obvious target here: It’s big and regressive. The catch is that it’s not controlled by the federal government, and Congress can’t lower it by fiat.

That doesn’t mean Congress is helpless: It could pass a federal rebate on state sales taxes. It could, for example, allow a federal tax credit based on an estimate of how much you paid in sales taxes. This would be calculated from your income and your state’s sales tax rate and would necessarily be approximate. But it would also be progressive.

And there’s one more big lever that could be used. A combination of these cuts could obviously send taxes below zero for some people. At that point, working- and middle-class families would lose the benefit of the cut since taxes can’t be less than zero.

Except they can: If a tax credit is refundable, it means your income taxes can become negative and the federal government owes you money. In all cases where it’s possible, progressive tax cuts should be refundable. The point, after all, is to give as much money as possible to the kind of people who will spend it to boost the economy. That means working- and middle-class families, who tend to spend most of the money they earn, as opposed to rich families who end up saving or investing much of it.

Will Republicans agree to any of this? Almost certainly not. They understand perfectly well who benefits from different kinds of tax cuts, and as 2017 demonstrated, they don’t care about spurring the economy or creating jobs for the middle class. Nor do they care about reducing the deficit or raising your wages. That was all just bread and circuses to keep the rubes happy.

What they do care about is increasing the income of corporations and the rich, and that’s what they’ll fight for. But if it’s a tax cut fight they want, Democrats can come armed with a slate of their own options. Maybe they won’t get everything they want. Maybe they’ll have to accept some Republican cuts in return for some of their own. But they’ll have a story to tell, and leverage, to get at least something for the middle and working classes.

In the past, Democrats have mostly just tried to gin up opposition to Republican tax cuts by pointing out how unfair they are. It’s never worked, but the fiasco of the 2017 cut, which even the Republican rank and file was lukewarm about, gives Democrats an opportunity to fight back. Instead of just opposing cuts even if there’s a strong case that we need them to stimulate the economy, they can propose better, more equitable tax cuts than Republicans. That would be something new: a chance to educate the electorate by having a showdown over competing tax plans. In the red corner, tax cuts for millionaires. In the blue corner, tax cuts for everyone else. That’s a fight worth having.