W.J. "Billy" Tauzin during his tenure as House Energy and Commerce Committee chairman in 2001. (Photo by Alex Wong/Newsmakers)

The following is excerpted from Wendell Potter and Nick Penniman’s new book, Nation On the Take: How Big Money Corrupts Our Democracy and What We Can Do About It. You can also listen to an interview with the authors.

Bill and Faith Wildrick have never heard of Billy Tauzin, but they’re paying dearly for Tauzin’s tireless work for the pharmaceuticbal industry. So are Faith’s employer and all of her co-workers. We all are. And in the future, so will our children and grandchildren.

Thanks in large part to Tauzin and Washington’s infamous revolving door, the Wildricks are paying so much to fill Bill’s prescriptions every month — even with their insurance — that they’re barely able to make ends meet. They and most of the rest of us, including the executives and employees of MCS Industries, the Easton, Pennsylvania, company where Faith works, also have to fork over more money to health insurance companies every payday because of the deals Tauzin cut for Big Pharma.

We can also thank Tauzin and many of his friends in Washington for increases in both our taxes and the national debt. In fact, by 2023, the US government’s debt will likely be more than a trillion dollars higher than it otherwise would be because of the way Tauzin and other lobbyists — with the blessing of President George W. Bush and Republican leaders in Congress — wrote the Medicare drug bill in 2003.

And in large part because of Tauzin’s deal making and the millions of dollars at his disposal, the Affordable Care Act — with the blessing of President Barack Obama and Democratic leaders in Congress — was written in a way that boosts drug company profits while doing little to make prescription medications more affordable for the vast majority of Americans. In fact, drug prices are going up at a faster clip than ever before.

As drug industry profits soar, millions of people — including most of our elected officials — continue to accept as gospel Big Pharma’s talking points that (1) any constraint on pharmaceutical companies’ ability to gouge us would “stifle” or “have a chilling effect” on innovation and (2) they have to charge Americans more because other countries won’t let them gouge their citizens. For the success of this propaganda we can thank the millions of dollars in dark money the industry spends every year on deceptive PR campaigns.

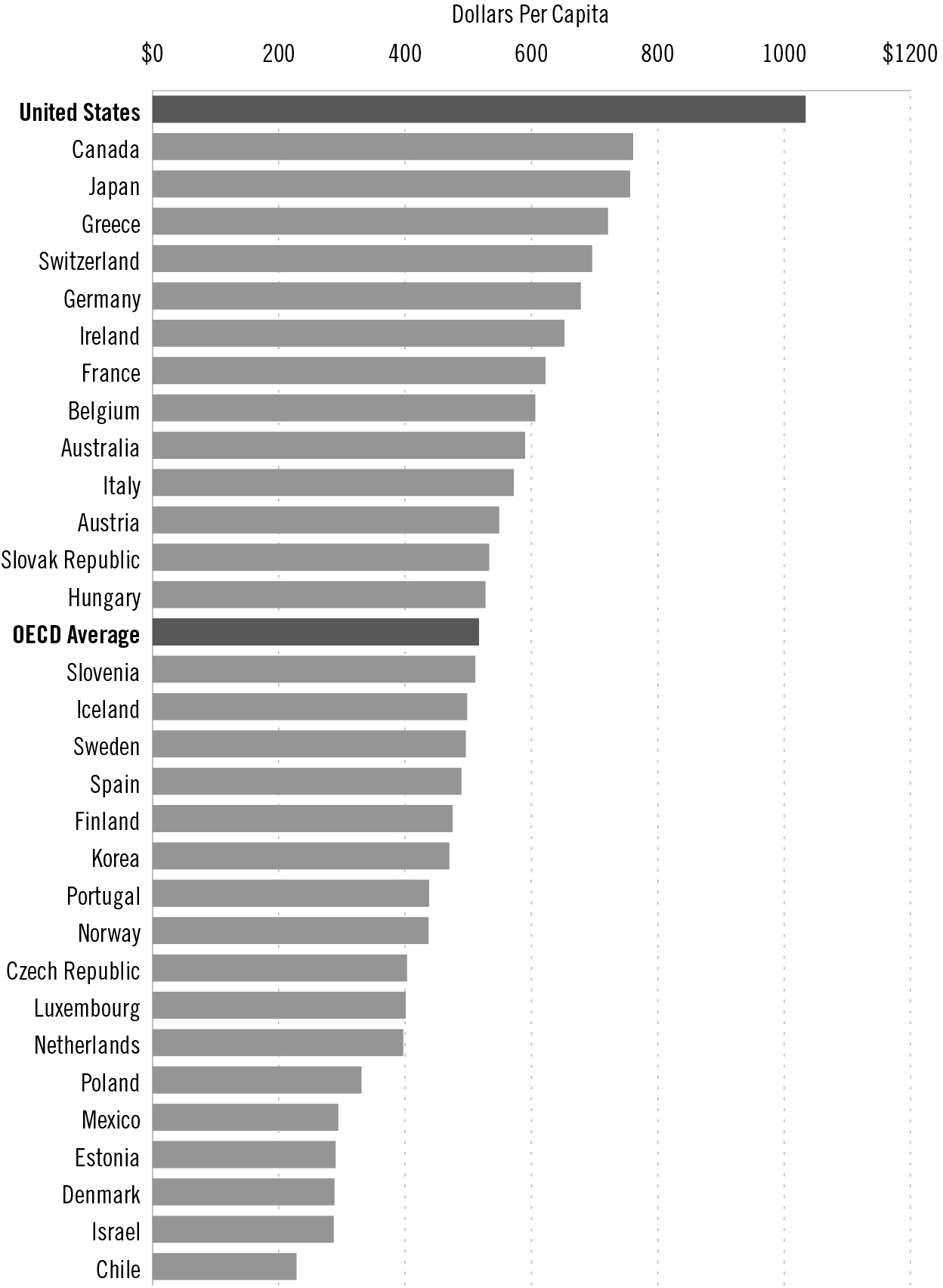

Americans pay far more for their prescription medications than citizens of any other country. In fact, we pay almost 40 percent more than Canada, the next highest spender on drugs, and twice as much as many European countries, including France and Germany. In 2013 we spent exactly 100 percent more per capita on pharmaceuticals than the average of the 34 countries that comprise the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), of which the United States is a member. And the portion of our tax dollars that go to Medicare likely will continue to increase because Congress, under the influence of the pharmaceutical industry’s cash, made it impossible for Medicare to negotiate with drug companies in order to lower costs.

In 1980, spending on health care in the United States totaled $255.8 billion. Of that total, we spent 39.3 percent on hospital care, 25.3 percent on physician/professional services, and 4.7 percent on prescription drugs. In just a little more than three decades, our total spending on health care exploded to $2.9 trillion. Between 1980 and 2013, the percentage of the total that we spent on hospital care dropped to 32.1, while spending on physician/professional services increased slightly, to 26.6 percent. Spending on prescription drugs, by contrast, almost doubled, to 9.3 percent.

Partly because of that steep increase, health care spending reached 17.4 percent of the US Gross Domestic Product in 2013, nearly double the average of 9.3 percent of the OECD countries. Spending on health care per person in the United States reached $9,255 in 2013, compared to the $3,484 average spent on health care per person in the OECD as a whole.

If you’re a young, healthy person you probably can’t even remember the last time you had to get a prescription filled. You may be wondering why you should even care about the rising cost of drugs and the ability of big corporations and their lobbyists to keep the status quo firmly in place.

US pharmaceutical spending, per capita, compared to other OECD countries

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Methodology: Numbers are per capita for 2013 or nearest year: Data not available for New Zealand, Turkey and the United Kingdom.

You should care because even if you’re not a regular customer at the pharmacy counter, you’re paying for the millions of other Americans who are, through taxes and health insurance premiums that are going up every year because drug companies have so many politicians, Democrats and Republicans alike, in their corner.

According to Express Scripts’ prescription price index, a branded drug that cost $100 in 2008 had almost doubled in price six years later. This rapid increase in drug prices is one of the reasons why health insurers and employers that offer coverage to their workers are constantly raising not only the premiums we have to pay but also our out-of-pocket costs through higher deductibles and coinsurance rates.

And if you do get sick enough to need meds that aren’t yet available in generic form, your insurer will make you pay much more for them than you would have just a few years ago. Since 2000, the average copayment for such drugs has doubled, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. And coinsurance rates for people who have to pay a percentage of their prescription drug costs instead of a fixed copayment have risen even faster. The average coinsurance rate for drugs was 14 percent in 2008. The rate had jumped to 32 percent by 2013, according to the consulting firm Towers Watson.

The Cagey Cajun

It’s worth taking a closer look at Tauzin’s life, both to understand the power a single industry wields over Capitol Hill and to witness the ways in which Washington’s revolving door works.

Born into a working-class French-speaking Cajun family in Lafourche Parish, Louisiana, Wilbert Joseph Tauzin II might have settled into the life of a construction worker — his father taught him how to wire houses and install air conditioners — had he not been bitten by the political bug even before college.

The “Cagey Cajun,” as he would later be called in Washington, was audacious enough to throw his hat in the ring for student council president of Thibodaux High School when he was just a sophomore. It was the first of many political campaigns he would win.

After graduation, he enrolled in Nicholls State University, which is just two and a half miles from his high school. Not being able to count on his family for much financial support, he worked, at various times, as an electrician’s helper, an oil rigger and a pipefitter to cover his tuition.

While in college, Tauzin realized that remaining loyal to a single political party has its drawbacks. Campus politics when he was a student was dominated by a party system. At the time, Tauzin, who later would be known as a conservative lawmaker, considered himself a Liberal. But when he sought the Liberal Party’s nomination for student body vice president, he came up a few votes short. Instead of supporting the Liberal candidate who beat him, however, the young Tauzin decided to stay in the race as an independent. He went on to victory.

He was a Democrat when the voters in Louisiana’s Third Congressional District elected him to Congress in 1980. Within a few years he had become one of his party’s assistant majority whips. He also would play a key role in bringing together a group of his conservative and moderate colleagues who came to be called Blue Dog Democrats, a name inspired by Cajun artist George Rodrigue’s famous Blue Dog paintings, one of which graced a wall of the congressman’s office.

But after the Gingrich Revolution of 1994, which put Republicans in charge of Congress, Representative Tauzin crossed the aisle and soon became the deputy majority whip for House Republicans. Thus he became the first member of Congress to have served in leadership positions of both parties. He’s “as wily as any alligator in the swamp,” former Tennessee congressman Jim Cooper, a Democrat, told The New York Times during the debate on what would ultimately become the Affordable Care Act.

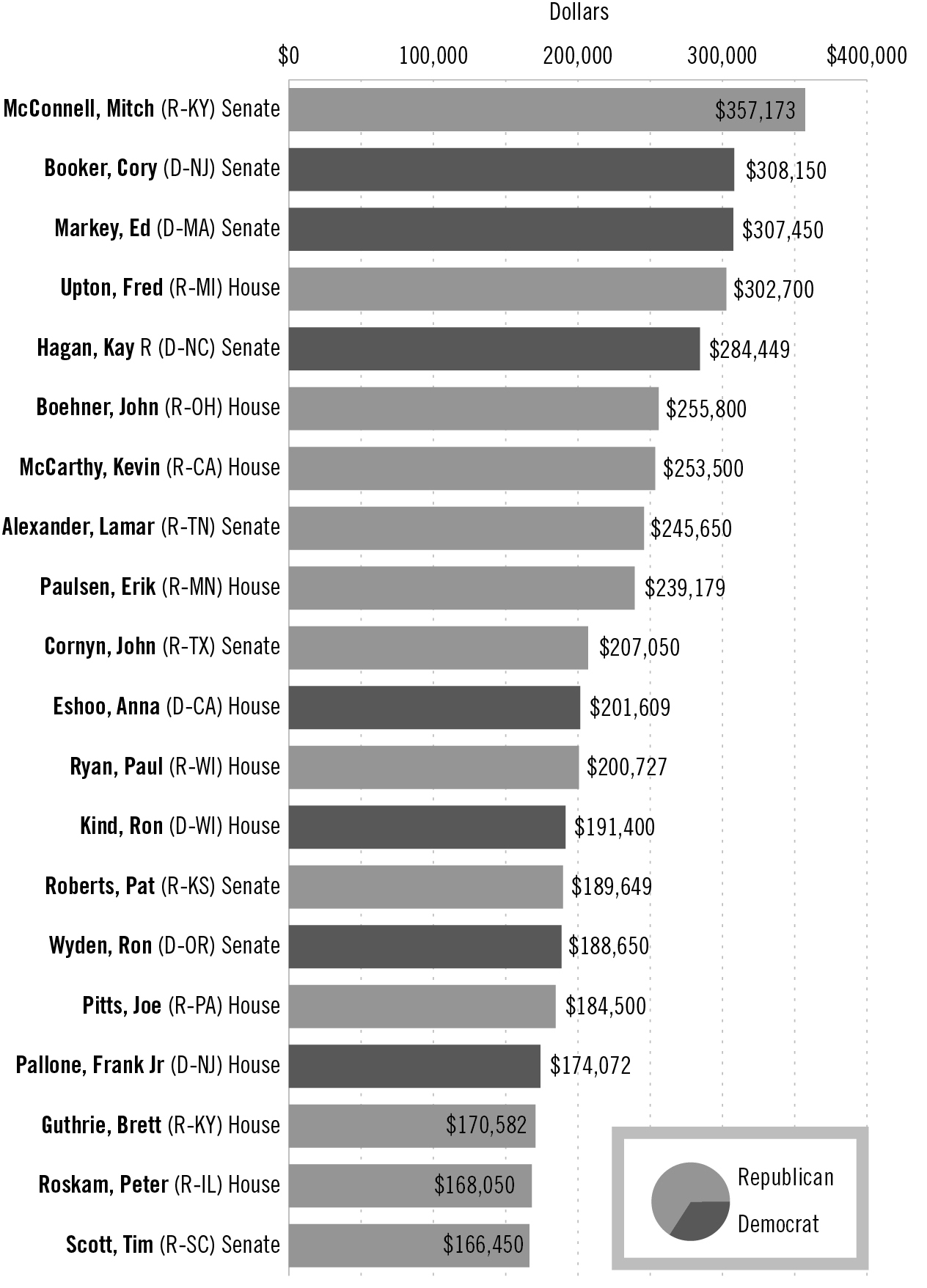

For many years, Tauzin was one of the pharmaceutical industry’s most important allies in Congress, especially from 2001 to 2004, when he chaired the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which oversees the Food and Drug Administration. While he held that chairmanship, drug companies and insurance and health professionals contributed nearly $1 million to Tauzin’s congressional campaigns, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. That’s chump change, though, compared to what the pharmaceutical industry paid him as its top lobbyist when he left Congress in 2005. His salary increased more than twelvefold — from $162,100 to $2 million — the minute he signed on as president and CEO of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the industry’s powerful trade group.

Top 20 recipients of pharmaceutical and health-sector contributions

Source: Center for Responsive Politics (opensecrets.org)

Methodology: The numbers above are based on contributions from PACs and individuals giving $200 or more. All donations took place during the 2013–2014 election cycle and were released by the Federal Election Commission on March 09, 2015.

PhRMA spent $26 million on lobbying in 2009, during the debate over the Affordable Care Act, to shape the law to its satisfaction. Individual companies within the pharmaceutical and health products industry spent millions more on top of that. In fact, at $275 million, the industry’s federal lobbying expenditures in 2009 stand as the greatest amount ever spent on lobbying by one industry in a single year, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. The total swelled to $558 million when lobbying expenditures from hospitals, medical device manufacturers and other health care companies and organizations were included. The industry also doled out millions of dollars in campaign contributions in 2008 and 2009, much of it to Democrats who ostensibly were in charge of writing the reform legislation.

PhRMA’s ability to influence elections and public policy has made it the envy of most other corporate advocacy groups in Washington. Not only is PhRMA consistently among the top spenders on lobbying activities every year, it is widely considered to be the most effective. The PR and consulting firm APCO Worldwide asked hundreds of the city’s movers and shakers in 2013 which of approximately fifty leading trade associations had the most clout. PhRMA came out on top, garnering the most wins in the most categories. It was voted the best at lobbying, the most effective at having a local and federal presence and the group whose members most frequently “mobilize to contact policymakers.” In other words, what PhRMA wants, PhRMA is very likely to get.

PhRMA, Clinton, Bush, Obama

Although Tauzin’s five-year reign at PhRMA proved extremely successful, the group has been a major force in Washington for more than twenty years. One of the industry’s most important victories came in 1994, when it teamed up with lobbyists for doctors, hospitals, medical device manufacturers and insurers to defeat President Clinton’s health care reform proposal. Clinton wanted to give Medicare the ability to negotiate with drug companies and to make it legal for medications made in the United States and exported to Canada and other countries to be imported back into the States and sold at lower prices. Both of those policy changes undoubtedly would have cut into drug company profit margins. But the Clinton reform legislation never made it to the floor of either the House or Senate for a vote. Industry lobbyists were able to kill it in committee.

Lawmakers of both parties tried to put those proposals back on the table nearly ten years later, when President George W. Bush, looking to shore up his support among older voters, pledged to work with Congress to add a voluntary prescription drug benefit — which came to be known as Part D — to the Medicare program. Not wanting to risk losing generous campaign contributions from the pharmaceutical industry, however, Bush and congressional leaders, including Tauzin, who by then chaired the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Republican House Speaker Dennis Hastert of Illinois and House Majority Leader Tom DeLay of Texas, invited drug company lobbyists to help shape what would become the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Also invited to the table were lobbyists for health insurers. They made certain that Medicare beneficiaries who wanted drug coverage would have to buy it from private insurers.

As Bruce Bartlett, who served as domestic policy adviser to President Ronald Reagan, wrote in The New York Times ten years later, enacting a new drug benefit — written by lobbyists without cost containment provisions — had Bush’s full support. “Looking ahead to a close reelection in 2004, he thought a new government giveaway to the elderly would increase his vote share among this group,” Bartlett wrote.

As it turned out, it would take all of Tauzin’s charm and wiliness as well as unprecedented flouting of House rules and procedures to pull off what Bush — and the lobbyists — wanted.

Early in the morning of Friday, November 21, 2003, just before the Thanksgiving break and after months of negotiations with drug companies and other special interests, a thousand-page bill finally landed on House members’ desks. To their astonishment, they were told they would have only a few hours to review it before having to vote on it.

Many Republicans were just as angry and upset as many Democrats, not only about the unrealistically short amount of time available to read and understand the bill but also about the fact that it would add hundreds of billions of dollars to the deficit while padding drug companies’ bottom lines. “The pharmaceutical lobbyists wrote the bill,” a disgusted Republican Representative Walter Jones of North Carolina’s Third Congressional District later told 60 Minutes after voting against the measure.

The timing of the vote was in itself unusual. What came next, however, was something that had never happened before in the history of the country. Jones said it was the “ugliest night” he had ever witnessed in more than two decades as a member of Congress.

Tauzin, Hastert and DeLay, who had received hundreds of thousands of dollars from drug companies during their political careers, knew it wouldn’t be easy to pass the legislation without a plan to pay for the costly new entitlement other than through permanent deficit spending. But they believed they had the support they needed when they called for a vote at 3:00 a.m. on Saturday.

When asked why he thought House leaders had scheduled the vote long after most Americans had gone to bed, Representative Dan Burton (R-IN), who also voted against the bill, said “a lot of shenanigans were going on that night (that) they didn’t want on national television.” Among the shenanigans, reportedly sanctioned by House leaders: freezing C-SPAN cameras and allowing lobbyists on the House floor as the vote was being taken. (Lobbyists who previously served in Congress had floor privileges until the enactment of the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007, which was passed in the aftermath of the Jack Abramoff lobbying scandal.)

Despite the arm twisting, the bill was still short of the 218 votes needed for passage after the standard 15-minute voting period. Rather than accept defeat, however, Hastert added two minutes to the voting clock. When that wasn’t enough, Hastert decided to keep the vote open indefinitely to give the pharmaceutical lobbyists more time to change minds.

Meanwhile, Thomas Scully, the former hospital industry lobbyist whom Bush had appointed to head the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and who had been the White House’s lead negotiator for the bill, waited nervously for the result. Scully had a personal as well as a political stake in the outcome of the vote. A few weeks before Congress had started debate on the bill, Scully had asked for — and been granted — a federal government ethics waiver from Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson, who also had a hand in writing the legislation. The waiver allowed Scully to ignore regulations that barred him from negotiating for future employment with anyone who might be affected financially by his work at CMS. It would be learned later that Scully was in talks with five firms whose financial interests would be affected by the legislation he would soon help to pass. He subsequently joined two of those firms. There were no repercussions.

As Scully knew, and as Bruce Bartlett noted in his New York Times op-ed, many House Republicans had said they would not vote for the Medicare drug bill if it cost taxpayers more than $400 billion over the first ten years. “Thus,” Bartlett wrote, “it was a huge problem for Republicans when the chief actuary of the Medicare system, Richard S. Foster, concluded during the summer of 2003 that Part D would actually cost $530 billion over its first ten years.”

It turned out not to be a problem at all, however, because Scully made sure Foster’s estimate would not see the light of day before the vote. Foster later wrote that Scully “ordered me to cease responding directly to congressional requests for actuarial assistance. Instead, I was directed to provide the responses to him for his review, approval and ultimate disposition. Following several vigorous discussions, the administrator made it clear that this was a direct order and that if I failed to follow it, ‘the consequences of insubordination are extremely severe.’ I understood this statement to mean that I would be fired if I provided the requested information to Congress.” An investigation into allegations against Scully, conducted a year later by the Office of Inspector General for the Department of Health and Human Services, substantiated Foster’s story and concluded that Scully had indeed threatened to sanction Foster if he released any information that Scully didn’t want members of Congress to see.

If Foster’s estimate — which turned out to be higher than the actual cost of Part D over the first ten years — had been made public, the bill would never have passed. In fact, it probably wouldn’t have passed had House leaders not allowed drug company lobbyists to pressure members directly on the House floor for hours.

As 4:00 a.m. approached, the industry was still three votes short, but House leaders and the industry’s platoon of lobbyists were not yet ready to concede. Their persistence finally paid off when Republican representative Ernest Istook of Oklahoma switched his vote. Seven other Republicans eventually followed Istook’s lead. When the “yeas” reached 220 at 5:53 a.m., almost three hours after the vote began, Hastert declared the bill passed. It was the longest electronic vote in congressional history.

Writing in the conservative National Review ten years later, Noah Glyn described the law as “perhaps the most prominent example of big government Republicanism during the Bush years.” Norman Ornstein of the conservative American Enterprise Institute called it a “huge trophy” for the Bush reelection team.

Indeed. Although his margin of victory over Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts in the 2004 general election was the slimmest in American history for an incumbent president, Bush received just enough additional votes from Medicare beneficiaries, especially in Florida with its 27 electoral votes, to make the difference.

Two days after the election, the New York Times reporter Robert Pear wrote that pharmaceutical and insurance company executives “were pleased and immensely relieved at the election results.” Bush’s reelection meant the Medicare prescription drug program would be implemented as those executives — and their lobbyists — envisioned (and helped write), and that any future proposals to add profit-limiting cost containment provisions would go nowhere. Even if legislation the drug companies and insurers didn’t like somehow made it through Congress, Bush could be counted on to veto it.

Also pleased and immensely relieved, with both the election and the bill Bush had signed into law, were many of the government employees, including members of Congress, who had worked on the legislation and were hoping it might lead to better-paying jobs. Within three years after Bush signed the bill into law, according to 60 Minutes, at least 15 members of Congress, congressional staffers and administration officials who had played a role in the bill’s passage had left office and joined the pharmaceutical industry.

Among them were Tom Scully and Billy Tauzin. Ten days after Bush signed the bill, Scully signed on with Alston & Bird, a large law and lobbying firm with numerous pharmaceutical clients, and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe, a private equity firm that invests in health care and information technology companies. Both were among the potential employers Scully was able to negotiate with thanks to his ethics waiver.

Tauzin, meanwhile, had to decide whether to accept a lucrative job offer from PhRMA right away or serve out the remainder of his term and avoid a potential conflict of interest investigation. He chose to wait and continued to serve as chairman of the committee that has jurisdiction over matters pertaining to the pharmaceutical industry. His spokesman repeatedly denied that PhRMA had offered Tauzin a job while the Medicare drug benefit legislation was being considered. Regardless of when the job offer was made, PhRMA waited for him. In January 2005, within days of his retirement from the House, Tauzin started drawing his $2 million salary as the organization’s CEO and chief lobbyist.

“To Trump Good Policy and the Will of the American People”

Three years later, after Democrats had regained control of both houses of Congress in the 2006 midterm elections, bills to control the cost of prescription medicines were introduced in both chambers. The House made the most progress when it passed a bill that would have permitted the reimportation of cheaper drugs. But over in the Senate, PhRMA, now led by Tauzin, was able to kill not only the reimportation bill but also the measure that would have given Medicare the ability to negotiate with drug companies. The industry’s massive lobbying effort and its generous campaign contributions to senators on both sides of the political aisle had paid off yet again.

Barack Obama, who was still the junior senator from Illinois, had supported both reform proposals. After the Medicare negotiation bill failed, he took to the floor of the Senate to express contempt for the way drug companies were able to call the shots on Capitol Hill. “Once again, a minority of the Senate has allowed the power and the profits of the pharmaceutical industry to trump good policy and the will of the American people,” he said. “Drug negotiation,” he added, “is the smart thing to do and the right thing to do, and it is unconscionable that we were not able to take up this bill today.”

Obama carried those sentiments into his bid for the presidency. His campaign even ran an ad depicting Tauzin as an example of what was wrong with politics. “The pharmaceutical industry wrote into the prescription drug plan that Medicare could not negotiate with drug companies,” Obama was shown telling a group of voters at a town-halltype meeting. “And you know what, the chairman of the committee, who pushed the law through, went to work for the pharmaceutical industry making $2 million a year.” That, he said, was an example of “the same old game playing in Washington.” He ended the ad with this: “You know, I don’t want to learn how to play the game better. I want to put an end to the game playing.”

That turned out to be just rhetoric, once the White House decided it would make health care reform a signature accomplishment of the Obama presidency. Obama’s top aides — including his chief of staff, the former congressional representative Rahm Emanuel of Illinois, and his deputy chief of staff, Jim Messina, who had worked for Senate Finance Committee chairman Max Baucus of Montana — were tasked with making sure PhRMA was kept happy in the ramp-up to the Affordable Care Act debate, and Baucus would become PhRMA’s main contact on Capitol Hill as the legislation was being crafted. The industry’s lobbyists made it clear to the White House that if the president was serious about enacting health care reform, drug companies and their cash could help him succeed — so long as he gave up on drug reimportation and Medicare negotiation and any other price control ideas he and congressional leaders might have in mind.

The Sunlight Foundation, a nonprofit transparency group, chronicled the deals the administration and congressional Democrats felt they had to cut to move ahead with the legislation. PhRMA dispatched 165 lobbyists — some of whom focused on the White House while the others worked the Capitol — to ensure that nothing would wind up in the legislation that drug makers couldn’t live with. As the Sunlight’s Paul Blumenthal wrote, many of those lobbyists, including Tauzin himself, would meet with top White House aides dozens of times “to hammer out a deal that would secure industry support for the administration’s health care reform agenda in exchange for the White House abandoning key elements of the president’s promises to reform the pharmaceutical industry.” If the White House agreed to the industry’s demands, drug companies would finance a $150 million ad campaign in support of what by then was beginning to be called Obamacare. It probably didn’t have to be said what would happen if the White House refused to accept the industry’s terms — drug companies would spend whatever it would take to kill reform, as they had done when the Clintons were in the White House.

A few months later, Baucus and Tauzin reached an agreement that Baucus would announce in a press release. Baucus said the pharmaceutical industry had agreed to “accept” $80 billion in cost-cutting measures over ten years — primarily by providing assistance to Medicare beneficiaries who were struggling with the out-of-pocket costs associated with the Part D prescription drug program. By contrast, Medicare beneficiaries could save almost $50 billion a year if the government could negotiate with drug companies in the same way that some European countries do, says economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Or even the same way as the US Veterans Administration, which has long had the ability to negotiate with drug companies. The VA pays an estimated 40 percent less than what Medicare pays for many of the same medications.

Much of the $80 billion Tauzin and Baucus settled on would be used to help close a big gap — called the “doughnut hole” — in the Medicare prescription drug program. One of the ways lawmakers and lobbyists were able to keep the ten-year deficit expansion figure of the Medicare Part D law below $400 billion back in 2003 was through a confusing and much-vilified gimmick to limit coverage — Part D enrollees would get coverage for the first $2,250 worth of medications, but after that they would fall into the so-called doughnut hole, as their coverage would not kick back in until they had paid a total of $3,600 out of their own pockets for their prescriptions. Under the Affordable Care Act, the gap will gradually shrink and finally disappear in 2020.

Although The Wall Street Journal’s editorial writers accused Tauzin of selling out PhRMA’s member companies by cutting the deal with the Democrats, the former congressman was betting that the drug makers would do just fine when millions of newly insured Americans under Obamacare would be finally be able to fill their prescriptions. It was a good bet.

— John McCain in 2012

When the details of the deal Baucus and the White House struck with PhRMA became known, it became clear to patient and consumer advocates that their hopes of getting significant relief from skyrocketing prescription drug costs had once again been dashed by politicians more beholden to drug company lobbyists than to the people who voted for them. And this time those hopes had been dashed by a Democrat in the White House who had won many of their votes by promising to end the game playing in Washington.

One of the longtime champions of legalizing the reimportation of prescription drugs, ironically, is Senator John McCain of Arizona, the Republican presidential nominee Obama defeated in the 2008 election. In 2012, two years after Obama signed the Affordable Care Act into law, McCain and Democratic senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio teamed up as cosponsors of a new reimportation bill. When he realized the drug companies would win once again through a combination of arm twisting by their phalanx of lobbyists and their strategic campaign contributions, McCain made no attempt to hide his disgust. “What you’re about to see is the reason for the cynicism that the American people have about the way we do business here in Washington,” McCain said as voting was about to begin. “PhRMA, one of the most powerful lobbies in Washington, will exert its influence again at the expense of low-income Americans who will again have to choose between medication and eating.”

PhRMA did indeed prevail yet again. McCain and Brown’s measure failed 43–54. The Senate’s Democratic leaders showed no interest in extending the voting period beyond the standard fifteen minutes to give McCain and Brown additional time to persuade some of their colleagues to switch their votes.

Public Research, Private Profits

In between these big legislative moments, PhRMA does the routine work of persuading policymakers of both parties that any proposed legislation or regulation that might hurt their bottom lines would most certainly inhibit the research and development of new drugs. People who are sick, they essentially claim, will just have to stay sick. Their talking points are carefully crafted to create a fear factor with lawmakers while also appealing to a distinctly American free market ideology.

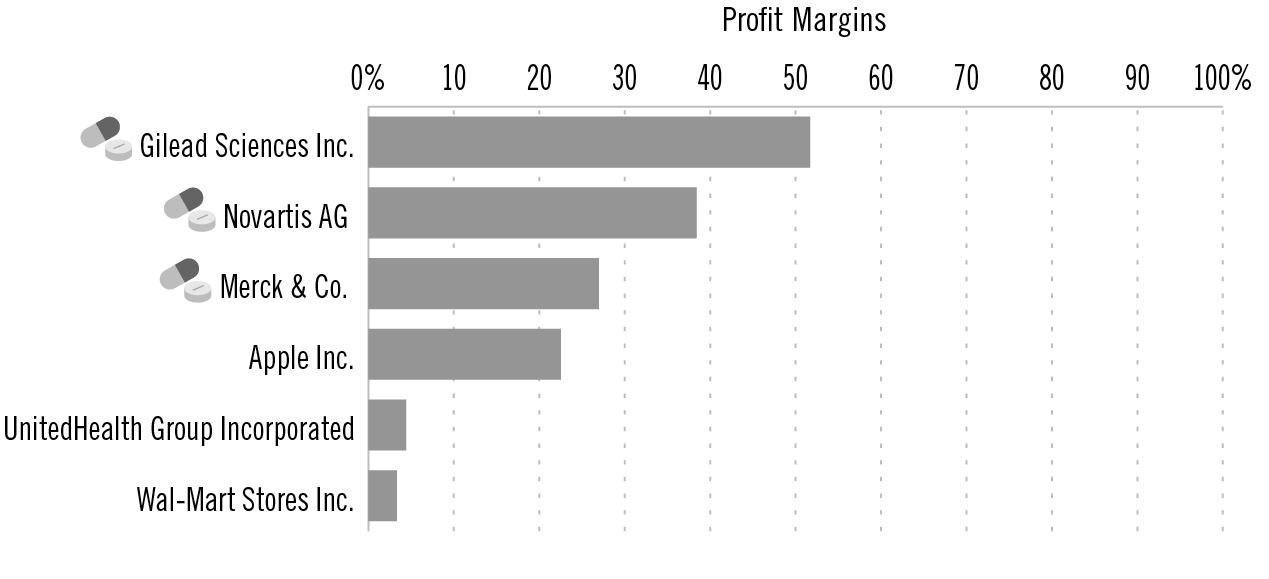

Yet the profit margins at these companies would indicate that they have plenty of extra cash on hand for R&D. Pfizer, one of the world’s largest drug companies as measured by pharmaceutical revenue, for example, recorded a profit margin of 42 percent in 2013. Even without the $10 billion the company made from the spinoff of a subsidiary, Pfizer’s profit margin would still have been 24 percent that year. It fell to 18.69 percent in 2014, trailing Merck’s 26.98 percent and Novartis’s 38.41 percent. Gilead Sciences’s profit margin stood at a stunning 51.69 percent.

2014 company profit margins: Drug companies are among the most profitable of any sector

Source: Yahoo! Finance

To put these numbers in perspective, the profit margin of the country’s largest health insurer, UnitedHealth Group, was 4.41 percent in 2014. Walmart’s was 3.32 percent, Apple’s was 22.53 percent.

It’s also worth pointing out that much of the R&D that goes into drug development is funded by us, the taxpayers. The industry’s often-cited cost for producing a drug is $1.3 billion over ten to fifteen years. But as the Harvard professor and former editor of The New England Journal of Medicine Marcia Angell notes in her 2004 book, The Truth About Drug Companies, most original research is done at universities and government agencies such as the National Institutes of Health. And many “new” drugs are slight variations of existing products with patents that are about to expire. Making such “me-too” drugs is just one of the ways pharmaceutical companies are able to extend their patents, a process known as “evergreening.”

Pharmaceutical companies do not disclose their exact research and development costs. Instead, they lump them in with other administrative costs that make it nearly impossible to fact-check their claims. But as Angell points out, drug makers spend far more on sales and marketing than on research.

This process — of profiting from publicly funded medical research — brings us back to the Wildricks. Gilead Sciences Inc. makes Sovaldi, the thousand-dollar-a-day hepatitis C pill that Bill Wildrick began taking in 2014. According to an analysis published in Clinical Infectious Diseases in January 2014, it likely costs no more than $136 to make a twelve-week course of Sovaldi. That’s $83,864 less than what the California-based company decided to charge for a twelve-week course in the United States.

No one else in the world pays nearly as much for Sovaldi as Americans do. In England, for example, the National Health Service was able to get the price down to $57,000 — still incredibly expensive but 33 percent less than what the company was able to charge customers in the United States, including the US Medicare program. The Indian government was able to negotiate an even better deal. As a result of Gilead’s willingness to give deep discounts to developing countries, the price per pill in India is $10 — a mere 1 percent of the cost in the United States.

Even at that price, though, the medication is beyond the reach of most of the 12 million people in India who the World Health Organization estimates have hepatitis C. Worldwide, as many as 150 million people, most of whom live in developing countries, may have hepatitis C, a chronic viral infection that often leads to cirrhosis of the liver or liver cancer.

Pharmasset Inc., a Georgia-based company that grew out of a lab at Emory University, developed Sovaldi, but much of the hepatitis C research that led to the drug was actually funded by taxpayers. As Modern Healthcare editor Merrill Goozner wrote in May 2014, the federal government invested heavily over more than two decades in university-based scientists “to understand the genetic weak points” of hepatitis C. Among the scientists the government invested in was Raymond Schinazi, the director of the Laboratory of Biochemical Pharmacology at the Emory School of Medicine who founded Pharmasset at Emory. (Emory received Pharmasset stock as partial consideration for licensing various technologies to the company.) His lab received at least $7.7 million over the past twenty years from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, according to government filings. As Goozner put it, Pharmasset and Schinazi “hit the jackpot” when Gilead, seeing the profit potential of Sovaldi, paid $11.2 billion for the company in 2012. Schinazi reportedly walked away from the deal with $400 million.

Because there were no constraints on what Gilead could charge for the drug, Gilead and its CEO, John Martin, would also hit the jackpot. Sales of Sovaldi exceeded $10.3 billion in 2014, the first year it was on the market. Gilead’s board was so pleased with the company’s revenues and resulting profit — net earnings for the year totaled $12.1 billion, compared to $3.1 billion in 2013 — that it awarded Martin $187.4 million in total compensation in 2014. “It’s not fair to ask public and private insurers and patients through their co-pays to be the only parties at risk in the nation’s search for miracle breakthroughs,” wrote Goozner, author of The $800 Million Pill: The Truth Behind the Cost of Drugs. “The long history of taxpayer-financed involvement in the development of Sovaldi only adds insult to the financial injury.”

An analysis published in February 2015 by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Biotechnology Information confirms Goozner’s assertions. It showed that more than half of the most transformative drugs — defined as pharmaceuticals that are both “innovative and have groundbreaking effects on patient care” — that were developed in recent decades had their origins in publicly funded research at nonprofit, university-affiliated centers.

As many critics have noted, the $1,000 Gilead charges for every Sovaldi pill it sold in the United States seems completely arbitrary, with no bearing on either the cost to produce the drug or the overall value of it. The company maintains that in the long run, Sovaldi, in combination with other drugs, is more cost effective than previous treatments for hepatitis C, in part because patients taking Sovaldi are less likely to be hospitalized. Possibly so, but Medicare spent $4.5 billion in 2014 on expensive hepatitis C medications like Sovaldi, which was more than fifteen times the $286 million it spent the year before on older treatments for the disease, according to federal data. And a recent study published in The Annals of Internal Medicine suggested that only about one fourth of the money spent on the costly new hepatitis C medications would be offset by avoiding hospitalizations and other treatment costs.

So why does Gilead charge us Americans so much? “The answer is because it can,” Steve Miller, chief medical officer of Express Scripts, the large St. Louis–based pharmacy benefit management company, told The Financial Times. “Other countries have come up with frameworks to make drugs affordable for people,” said Miller, “whereas in the US it has always been a case of what the market will bear. We think the market is no longer bearing up.”

Those “frameworks” are another term for laws constructed on behalf of the common good — the kinds of laws that, because of the power of the pharmaceutical industry over Congress, we seem incapable of passing. And it is the lack of such lawmaking that forces Bill and Faith Wildrick to live paycheck to paycheck and give up many of the things they used to do that they can no longer afford.

Bill and Faith both worked at MCS Industries, which has grown since its founding in 1980 to be one of the country’s largest suppliers of wall and poster frames. It has also become one of the biggest employers in Easton, Pennsylvania, which is about sixty miles north of Philadelphia. Faith Wildrick, who packs boxes of frames to send to customers around the world, joined the company in 1993. Bill joined the company two years earlier and was there for more than twenty years, until he got so sick and weak from hepatitis C that he could no longer work.

Bill is one of an estimated 3.2 million Americans who have hepatitis C, although most of them don’t know it because symptoms often don’t develop until decades after infection. But the virus, which attacks the liver, can be a killer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that as many as ten thousand Americans die every year from liver cancer and cirrhosis caused by hepatitis C. Bill believes he was infected in the 1970s, during a time of his life when he occasionally used drugs. The most common way to get hepatitis is by sharing needles, although some people can become infected through sexual contact. (Prior to 1992, many people also got hepatitis C through blood transfusions, but since then, all donated blood and organs are screened for the virus.) Bill said he remembers sharing a needle only one time. But one time was all it took.

It’s not just Baby Boomers like Bill who are infected and facing enormous health care costs, by the way. In May 2015, the CDC reported a huge increase in rates of hepatitis C infections among people under thirty, especially in rural areas. The biggest increases were in four Appalachian states — Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia — where infection rates jumped 364 percent between 2006 and 2012. Three fourths of the new cases were the result of young people sharing needles to inject prescription drugs.

When Bill’s health began to deteriorate a few years ago, he was tested for the virus and told that not only did he have it, it had already begun to damage his liver. His doctor put him on interferon, the most prevalent treatment for acute hepatitis C at the time. After six months on the drug, which is notorious for its debilitating side effects, Bill still had the virus. He was then prescribed Pegasys, another drug with similar side effects. When tests showed that Bill still had the virus after six months on Pegasys, his doctor told him about a new drug that the FDA had approved just a few months earlier (in December 2013) and that clinical trials had shown had a 90 percent cure rate if taken every day for twelve weeks in combination with other drugs. The new drug was called Sovaldi.

Bill said his heart sank when he was told that Gilead Sciences, which owned the patent on the drug, had priced it at a thousand dollars a pill. He would also have to take another drug, ribavirin, which would make the daily cost even higher. But he was in luck. Both he and Faith were covered under a Blue Cross health plan Faith had enrolled them in at MCS. After confirming that the policy would cover the drugs, Bill started treatment in April 2014.

Unfortunately, Bill was one of the 10 percent who still had the hepatitis C virus at the end of twelve weeks. His doctor said he needed to keep taking the drugs. Many more weeks went by. By the time his doctor said he could stop taking them, in October 2014, he had been on the medications for six months. Six months at more than a thousand dollars a day.

Although Blue Cross covered most of the costs associated with his treatment, the Wildricks still had to pay several thousand dollars out of their own pockets because they were in a high-deductible plan. Faith said their out-of-pocket costs in 2014 totaled more than $4,000 for Bill’s medications alone. “Not only do I constantly worry about Bill,” Faith said, “I worry every time he goes to the doctor about whether our insurance will cover it.” She said she dreads checking the mail when she gets home from work because of all the bills they get from Bill’s doctors and the Philadelphia hospital where he had to go on a frequent basis for testing. “Now that Bill can’t work, our income has gone way down,” Faith said. “So things have gotten a lot tighter. We’ve had to cut down on a lot of things. We used to try to go on a vacation every year, but we can’t afford to do that anymore. You have to think about everything you spend. You can only stretch your paycheck so far.”

Faith said she also can’t help but worry about what would happen to them if she got sick and couldn’t work or lost her job. “I’m the main source of income, and if I got sick, it would be devastating. I have no idea what we would do.”

The Wildricks are not the only ones who are paying dearly for the high cost of Bill’s medications. So is MCS. Richard Master, the company’s CEO, said the amount of money MCS had to pay for drugs for the 320 employees and dependents who were enrolled in the company’s health plan in 2014 was far more than in any previous year. That probably would have been the case had Bill Wildrick been the only one covered under the company health plan who was being treated for hepatitis C. Unfortunately, there were two, the other being an employee in his fifties who was on Sovaldi and ribavirin for twelve weeks. Altogether, the cost of the hepatitis C drugs the two men took in 2014 was more than $260,000. Master said that that was more than 15 percent of MCS’s total health plan expenditure for the year.

MCS’s experience would come as no surprise to Brian Klepper, CEO of the National Business Coalition on Health, a nonprofit organization comprising more than four thousand employers that offer health benefits to their workers. As he knows all too well, a growing number of employers across the country are experiencing similar rate increases as a result of ballooning specialty drug costs.

“The possibility of specialty drug pricing financially overwhelming business and union health plans is real,” Klepper wrote in a May 28, 2015, commentary for Employee Benefit News. His prediction for the future of employer-sponsored health benefits was dire:

Purchasers will be alarmed to find that their drug costs are growing much faster than other, already exorbitant health care spending. CFOs and benefits managers will watch their specialty drug spending, and calculate. To their minds, excessive specialty drug costs could capsize their plans, making it untenable to maintain good health coverage without compromising some other important health plan benefit. Just as worrisome, these costs will substantially increase their already heavy health care burdens, eating into the bottom line.

Klepper added, “Unless something changes, in just another five years we’ll likely spend more on specialty than nonspecialty drugs. Or, for that matter, on doctors.”

The sharp and unexpected spike in drug costs at MCS didn’t go unnoticed by the company’s insurer, Blue Cross, which hit MCS with a 14 percent premium increase for 2015. That was the biggest rate hike in the company’s recent history. Master’s insurance broker recommended that MCS switch to Cigna, which was willing to cover the company’s workers at a rate that was still considerably higher than what MCS had paid Blue Cross in 2013. Even with the change, employees saw their premiums increase, and some of the hospitals that were in the Blue Cross network were not in Cigna’s. That was bad news for Bill Wildrick, who was told by Cigna that if he didn’t switch to a different hospital for his regular testing, he would have to pay much more out of his own pocket.

He also got more bad news in early 2015: even after six months on Sovaldi, he still had the hepatitis C virus. The good news was that Gilead had just released a new drug that might work better. The drug, Harvoni, is actually a combination of Sovaldi and the other drug that Bill had been taking, ribavirin. The catch: the wholesale price of Harvoni is $1,125 per pill. A three-month supply costs $94,500.

It’s Not Just Sovaldi

Billy Tauzin’s January 2005 announcement that he had decided to take PhRMA up on its two-million-dollar-a-year job offer came ten months after another big announcement from his office: he had cancer.

On March 10, 2004, the congressman’s spokesman, Ken Johnson, said his boss would have surgery the following week at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he had been diagnosed a few days earlier with cancer of the duodenum, a part of the small intestine. “His doctors have assured him he’ll live a long, healthy and productive life,” Johnson told CNN at the time. That’s not at all how Tauzin later characterized what he had been told at Johns Hopkins. After the surgery, he said in a 2009 interview, “The doctor told me very frankly that I was going to die.”

“My doctor reviewed my options with me,” Tauzin said in the interview. “I could undergo another surgery, but that would probably kill me and would be unlikely to cure the cancer. They had no approved protocol for people in my position, but there was a drug (Avastin) that had been successful in treating colon cancer but was not yet approved for duodenal adenocarcinoma. The drug works by cutting off the blood supply to tumors, which meant that the drug could either damage my healing process or kill the cancer. My wife and I decided to take the risk because we had very little to lose. It was really a choice between ‘going to die’ — my current situation — and ‘might die’ — Avastin could cure me. It’s a good thing we tried Avastin because it worked like a miracle. By the end of my first round of chemotherapy, the radiologist couldn’t even find the tumor on my CT scans. It was gone. I completed several courses of chemo and radiation and I’ve been cancer-free for over five years now.”

He said it was his wife who suggested after his recovery that he take the PhRMA job. “‘You know, Billy,’” he said she told him, “‘you really ought to go to work for the people who saved your life.’ And I thought, ‘If there’s a meaning in why I’m alive today, then surely it must be to use my experience to help patients like me across the world.’”

As he has told the story about his recovery, Tauzin has made no mention of how much Avastin and many other cancer drugs now cost. There is no question that many of the products pharmaceutical companies sell save thousands of lives every day. But how long will patients — and the nation as a whole — be able to afford those products? Like Sovaldi, Avastin, one of the most widely used cancer drugs in the world, is incredibly expensive. It’s not unusual for patients — or their insurers or Medicare — to be charged $9,000 a month for Avastin. But as The New York Times has reported, studies have shown that for most patients, Avastin prolongs life for only a few months at best. Nevertheless, sales of Avastin, marketed by the biotech firm Genentech, reached $6.6 billion in 2013.

The next year, Genentech implemented a scheme to make even more money from the drug. In a widely criticized move, the company, which became a subsidiary of Swiss-based Roche Holding, notified US hospitals in 2014 that they could no longer buy Avastin from the wholesalers they had been buying it from for years. Going forward, they would have to buy Avastin and two of the company’s other cancer drugs through Genentech-approved specialty distributors. That shift, as Time reported, meant that hospitals would no longer get an estimated $300 million in discounts they’d been getting from the wholesalers. Instead, Genentech and the specialty distributors would be able to pocket the money.

Pharmaceutical companies have also been repricing their cancer drugs on a regular basis to boost profits. Prior to 2000, the price of cancer drugs for one year of treatment typically ranged between $5,000 and $10,000. By 2012, the average had risen to $120,000.

Another way of looking at it is the cost per additional year of life made possible by the drugs. In 1995, a group of fifty-eight leading cancer drugs cost on average about $54,100 for each year of life they were estimated to add. By 2013, those drugs cost about $207,000 for each additional year of life.

The rapid increase in costs, coupled with the aging of the US population, led the National Institutes of Health to project in 2011 that medical expenditures for cancer in 2020 will reach at least $158 billion — 27 percent more than in 2010 — and could go as high as $207 billion. Speaking at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago on May 31, 2015, Dr. Leonard Saltz, chief of gastrointestinal oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, called the rapid cost of cancer drugs “unsustainable.” He said the median monthly price for new cancer drugs in the United States had more than doubled over the past decade — from $4,716 in the period from 2000 through 2004 to $9,900 from 2010 through 2014. That increase, he said, could only be explained by the desire of pharmaceutical companies to boost profits. “Cancer-drug prices are not related to the value of the drug,” he said. “Prices are based on what has come before and what the seller believes the market will bear.”

At the same time, many patients — including cancer patients — are finding that drug companies are not making adequate amounts of some lifesaving medications because they’re not as profitable as they once were. The Wall Street Journal reported in May 2015 that BCG, a drug used to treat bladder cancer, is now in short supply because the twenty-five-yearold drug is no longer protected by patent. BCG sells for $145 a vial, a fraction of the $2,700 Genentech charges for a vial of Avastin. As the Journal noted, there has been no shortage of Avastin.

If anything, spending will go even higher. In 2014, total prescription drug spending in the United States rose to $374 billion, an increase of 13.1 percent in just one year, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Driving the big increase were the emergence of Sovaldi and other new expensive specialty drugs and pharmaceutical companies’ decision to slap new price tags on their older medications, their older specialty drugs in particular. Indeed, spending on specialty medicines, not just for hepatitis C and cancer but also for other diseases such as multiple sclerosis, jumped an unprecedented 31 percent, according to an analysis by Express Scripts, the pharmacy benefit management firm. The company noted in an earlier report that while specialty drugs accounted for less than 1 percent of all US prescriptions, they accounted for 27.7 percent of the country’s total spending on medications in 2013. It projected spending on specialty drugs would increase 63 percent between 2014 and 2016.

Not only are brand-name drugs being priced at unprecedented levels, so are generics, which until recent years had been decreasing in price. A survey conducted by AARP and published in May 2015 showed that one in four generic medicines used widely by older Americans increased in 2013. “This is the beginning of a shift,” Leigh Purvis, AARP’s director of health services research, told the Associated Press. “What we used to get from generics in the way of savings is going away at the same time that the prices of brand-name drugs are extremely high, and they’re going even higher.” She called some of the price increases “stratospheric.” Among them were two generics used for treating infections whose retail prices increased more than 1,000 percent in 2013.

In his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama stressed the importance of committing taxpayer dollars to help finance the development of “precision medicine” — personalized therapies to treat a broad range of illnesses. He asked Congress to allocate $215 million to get the initiative under way.

“The possibilities are boundless,” he said at a subsequent White House event. “It [precision medicine] gives us one of the greatest opportunities for new medical breakthroughs that we have ever seen.” Obama mentioned cystic fibrosis in particular, noting that people with certain mutations in a particular gene are now being treated successfully with a new precision drug called Kalydeco. As The New York Times later noted, Obama did not mention that the list price for a one-year supply of the drug is $311,000. The cost of Kalydeco and other specialty drugs is fueling a huge increase in government spending on the Medicare Part D program. The Obama administration’s budget proposal for 2016 had this stunning projection: Part D benefits were expected to increase 30 percent in one year’s time — from $63.3 billion in 2015 to $82.5 billion in 2016. Deep inside his $3.99 billion budget request to Congress for 2016, Obama once again proposed giving Medicare the ability to negotiate prices for expensive drugs. But as long as Washington’s revolving door keeps spinning, and industries can spend hundreds of millions of dollars to finance the political campaigns of the politicians who are supposed to be regulating them, PhRMA almost certainly will continue to rule Capitol Hill.