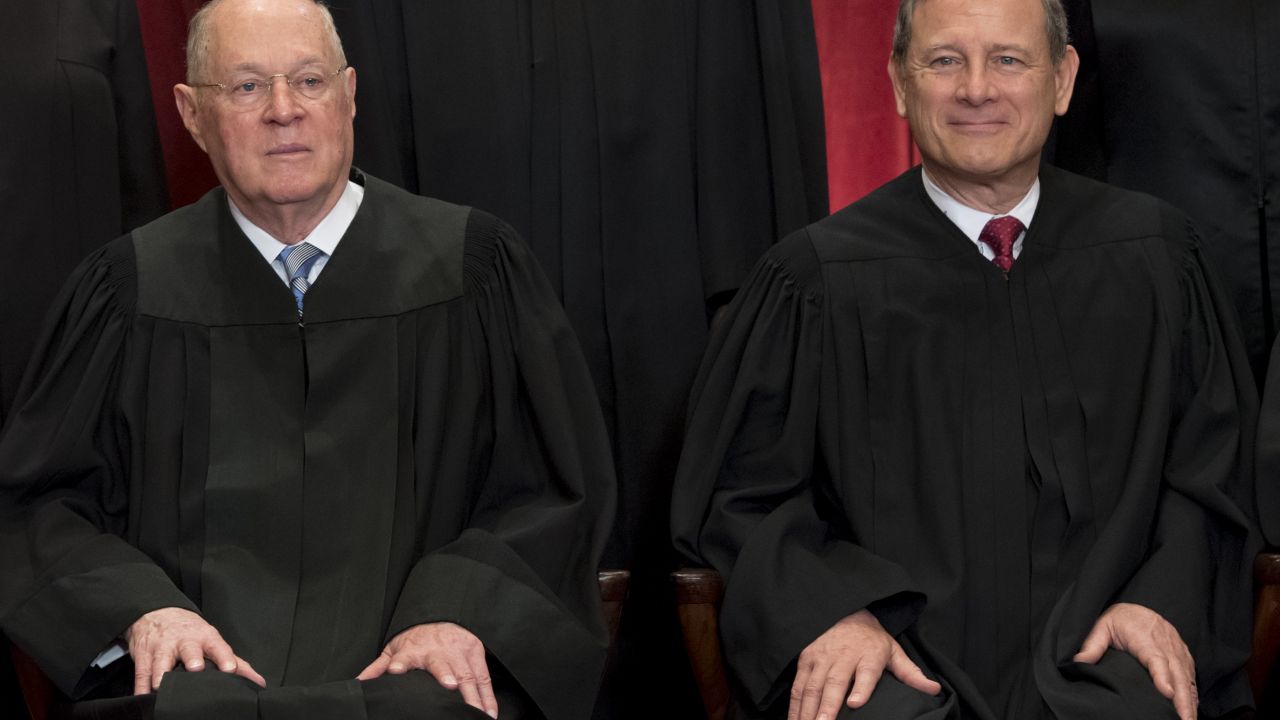

Chief Justice of the United States John G. Roberts (right) and US Supreme Court Associate Justice Anthony M. Kennedy (left) in an official photo in 2017. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images)

When the worst blizzard in 130 years pummeled Madison, Wisconsin in February 2011, something impossible happened: It stranded Green Bay Packers fans trying to travel to Texas for the Super Bowl.

But even a storm powerful enough to deter hardy crazies known for cheering shirtless in sub-zero temperatures could not stop one thing: Partisan gerrymandering.

That job now rests with one man: Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Kennedy will now scrutinize the constitutionality of the Wisconsin state assembly districts that the Republican operatives worked through a blizzard to craft. They delivered exactly as intended. In 2012, the first election held on these maps, Democratic candidates won 174,000 more votes. Republicans, nevertheless, won 60 of 99 seats.

That tilted outcome, however, launched the litigation that now provides the best hope in more than a decade of defeating gerrymandering — the toxic art of manipulating maps for partisan advantage — once and for all.

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Gill v. Whitford. The stakes could not be higher, or the court more closely divided. Kennedy, long alarmed by partisan gerrymandering but never convinced that there’s a fair way to determine when it has gone too far, looks like the deciding vote.

It’s a position he asked to be in, and a case he practically invited before the court. “Now we will see if Kennedy was being truthful,” said Norm Ornstein, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. “He asked for a standard. The Wisconsin case provides a very clear example.”

When the Supreme Court last addressed partisan gerrymandering, in the 2004 case Vieth v. Jubelirer, Kennedy sided with a 5-4 conservative majority that rejected an argument from Pennsylvania voters who claimed an aggressive GOP gerrymander interfered with their constitutional right to equal protection.

But while Justice Scalia and three other conservatives wanted to call partisan gerrymandering non-justiciable and slam the door on the court’s involvement in future challenges, Kennedy kept it cracked, unprepared to declare that a fair standard could not someday emerge. Then he dropped breadcrumbs along the path reformers would need to follow to earn his backing next time.

It must be a “limited and precise rationale,” based on a “clear, manageable and politically neutral standard” that shows partisanship was “applied in an invidious manner” or in such a way “unrelated to any legitimate legislative objective.” Kennedy observed that while sophisticated new mapmaking software represented a potential threat to democracy, “these new technologies may produce new methods of analysis that make more evident the precise nature of the burdens gerrymanders impose on the representational rights of voters and parties.” If so, he concluded, “courts should be prepared to order relief.”

“The thing that I took away from the concurring opinion was that he believes that extreme partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, so long as we can come up with a standard,” said Gerry Hebert, who argued and won the lower court cases in Whitford, and the executive director of the Campaign Legal Center. “Secondly, he expressed, the hope that there would someday be a standard.”

The Wisconsin case hinges on a three-part test that convinced a lower court last year to declare the GOP maps unconstitutional. First, they presented evidence of discriminatory partisan intent, including dramatic emails between strategists declaring plans to “wildly gerrymander” and dozens of draft maps with titles like “aggressive” and “assertive.”

Then they developed a new standard called the “efficiency gap,” which measures a partisan gerrymander by counting the number of votes on both sides that do not contribute to victory. It helps demonstrate whether a party held an unfair advantage in converting votes into seats. When compared across states and over five decades, the Wisconsin gerrymander was one of the 18 worst in modern history.

“What I think we have here, for the first time, is a standard that can be applied by judges,” said Hebert. “It’s not difficult math. This is 6th grade math we’re talking about here.”

— Gerry Hebert, executive director of the Campaign Legal Center

The final part of the standard considers whether there is a compelling justification for the districts being drawn in such a way — such as compliance with the Voting Rights Act, or holding communities of interest together.

While some of the faces have changed since Vieth, none of the four conservative justices, or the four liberals, seem likely to be moved. So what about Kennedy? Will the efficiency gap and these other measures be enough to bring about the first constitutional standard on partisan gerrymandering in our history, right on the eve of the 2020 midterms and the next round of redistricting? Longtime watchers are struggling to read his mind.

“It’s not clear to me that the standards that are proposed are different in kind from what was already addressed in Vieth,” said Richard L. Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine. “But there are two differences from then. One is that there now seems to be a scholarly near-consensus that it’s possible to do a partisan gerrymander that lasts an entire decade, thanks to improvements in data and computer technology. That might weigh on Justice Kennedy. It imposed more of a hardship on voters.”

The other difference: Kennedy’s retirement appears close at hand. “This is set up as potentially the last big opportunity for him to do something about partisan gerrymandering. He’s much more likely to do something than someone else that Trump might nominate. He has to know that.”

Other scholars express some skepticism about whether the efficiency gap is actually the game-changing standard that some have suggested.

“This case looks pretty much like Bandemer and Vieth,” said Bradley A. Smith, the former chairman of the Federal Election Commission and chairman of the conservative Center for Competitive Politics. “The efficiency gap doesn’t add much to the analysis. Note that the lower court merely saw the ‘gap’ as evidence, not some new, killer theory.”

Smith argues that Kennedy’s position in Vieth remains about right: It’s not wise to close the door on the possibility that a gerrymander could be unconstitutional, “but as a practical matter, that would be a rare case and very difficult to prove,” he said. “There’s no right to win political races, so unless a gerrymander really boxes out voters over time, it’s not a constitutional problem. I don’t think [Whitford] gets there. But what Kennedy thinks, I don’t know. I don’t see clues in his other writings.”

Michael McDonald, however, a professor at the University of Florida and one of the nation’s leading redistricting experts, pointed to Kennedy’s decision in Cooper v. Harris as one potential signpost. In May, when the Court overturned two North Carolina congressional districts last month as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, Kennedy disagreed and signed onto a dissent by Justice Samuel Alito that expressed concern about whether the Supreme Court ought to arbitrate partisan gerrymandering at all.

McDonald is also unconvinced that the efficiency gap necessarily meets Kennedy’s call for a clear and manageable standard.

“The efficiency gap is fundamentally the same as every other measure that has been put before the court. Fundamentally it’s about translating votes into seats and how well the system does that,” he said. “Kennedy himself has been skeptical of these methods that have been put before him in amicus briefs.

“I just don’t see it. There’s no bright-line standard in the efficiency gap as to say when a redistricting plan is unconstitutional,” he said, arguing that because election conditions and redistricting processes are variable across states, it’s impossible to draw meaningful comparisons.

If the Whitford plaintiffs carry the day, McDonald said, it’s could be because there have been multiple elections in Wisconsin with anti-majoritarian outcomes.

“By multiple measures — not just the efficiency gap — there’s ample evidence to say ‘this is a stacked system,’” he said. “I would hope that Kennedy would take a similar approach that is used in racial gerrymandering cases, look at all the evidence together, and let the courts come to a decision. I hope he will movie in that direction and articulate something in that way. But the efficiency gap alone, I fear, is not going to do it.”

Hebert, however, maintains that the efficiency gap need not be a silver-bullet democracy theorem to carry the day, that Kennedy could simply view it as one useful tool among others. He also knows that time is running out, and that the replacement of Kennedy or any of the four liberal justices by President Trump could provide the fifth vote to make any future partisan gerrymandering cases non-justiciable for good.

“If we don’t win this case, I don’t have much hope that it will happen in my lifetime, if at all,” Hebert said. “Kennedy would really be giving America the greatest gift. We’ve lost a lot of our democracy, and he would give it back to us. That would be an awesome thing to leave as a legacy for his time on his court.”