“When the middle class has to subsidize huge corporations like Walmart that criminally underpay their workers, the narrative that we are overtaxed ought to be outed as ludicrous,” says Connecticut state Rep. Josh Elliott. (Photo by Damian Gadal/ flickr CC 2.0)

This post originally appeared at Inequality.org.

Josh Elliott is fed up with overpaid CEOs. As the owner of a suburban Connecticut natural foods market with 40 employees, he says he could never justify pocketing hundreds of times more pay than his employees.

“I’m very much a capitalist,” Elliott told me in an interview. “But there need to be limits.”

Skyrocketing CEO pay and inequality last year motivated this 32-year-old businessman to launch a successful bid for a seat in the Connecticut General Assembly. Elliott hit back hard on the campaign trail against right-wing claims about high taxes driving wealthy job creators out of his state.

“This is not an issue of over-taxation — it’s an issue of taxing the wrong people and the wrong entities,” he told the New Haven Register. “When the middle class has to subsidize huge corporations like Walmart that criminally underpay their workers, the narrative that we are overtaxed ought to be outed as ludicrous.”

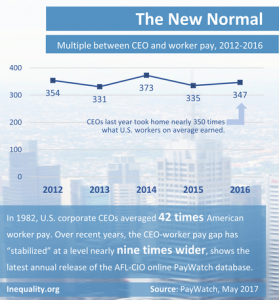

Since taking office, Rep. Elliott has co-sponsored several bills aimed at narrowing our economic divide, including two that directly address the CEO pay problem. One of these bills mirrors a Portland, Oregon law enacted last December that imposes a tax penalty on publicly traded corporations with CEOs making more than 100 times their typical worker pay.

Such tax policies do not set a ceiling on how much corporations can pay their executives. But they do provide an incentive to reduce executive compensation and lift up pay for workers at the bottom end. They can also generate significant revenue for urgent needs like funding pre-school programs or fixing roads and bridges.

Legislators in Illinois, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and San Francisco are also considering CEO pay tax proposals.

Elliott’s other CEO pay ratio bill would use the power of the public purse to discourage paycheck disparities. If enacted, companies with CEO-worker pay ratios of more than 100 to 1 would not qualify for state subsidies and grants. Such policies would help ensure taxpayer dollars are used wisely. Research has shown that narrower pay gaps make businesses more effective by boosting employee morale and reducing turnover rates.

Elliott pointed out that he’s able to go to the state capital in Hartford four times a week when the General Assembly is in session because he trusts his managers to do a good job running the market in his absence.

“I might bring a lot of the vision and quality control,” he told me. “But you need to have good employees to make money.”

While efforts to narrow CEO-worker pay gaps are spreading around the country, Republicans in Washington are working to undercut them. How? By killing a federal disclosure law requiring corporations to report every year on the gap between their CEO and median worker pay. This federal data source, scheduled to become available in early 2018, would make the kinds of policies Elliott is promoting much easier to administer.

But overpaid CEOs want to throw up as many obstacles as they can. Last week their lobbying paid off when the House Financial Services Committee approved the Financial CHOICE Act. Buried in this massive bill to loosen regulations on big Wall Street banks is a provision that would eliminate the pay ratio disclosure regulation. The bill could come up for a vote in the full House of Representatives in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, Elliott will continue to work on shifting the debate in his state and is confident that these types of bold proposals for change will eventually gain traction.

“The conservative narrative is that business owners are the job creators,” he told me. “But if the CEOs and owners of capital have unlimited potential for their own compensation, they’re just taking money away from their employees. And that’s a system that is simply unsustainable.”