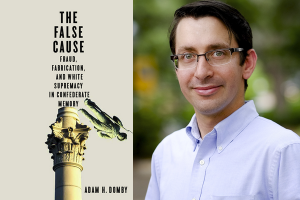

Adam Domby, an award-winning historian and specialist on the Civil War and Reconstruction, examines the role of lies and exaggeration in the Lost Cause narratives and their celebration of white supremacy in his timely and groundbreaking new book The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory (University of Virginia Press, 2020).

Members of the Minneapolis Police Department killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man, on May 25, 2020. The shockingly brutal 8 minute and 46 second televised asphyxiation of Mr. Floyd sparked nationwide outrage and protests against police brutality and the many forms of systemic racism.

Mr. Floyd’s death also led to renewed efforts to remove Confederate monuments that celebrate slavery, treason, white supremacy, and racism. In several cities, public officials or protesters removed these memorials. The Southern Poverty Law Center reported in 2018 that more than 1,700 monuments to the Confederacy stood in public places. Many remain.

As the president shares racist talking points and vows to protect all memorials, including the Confederate tributes, many Americans are learning more about their history, particularly about the cruelty of slavery, the treason of the South to defend this brutal enterprise, the postwar defeat of Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era of rigid segregation and disenfranchisement of Black citizens.

The Confederate monuments were constructed as reminders to white citizens of their supposed racial superiority while they were meant to intimidate and even terrorize Black people and keep them subservient. Most of these statues were erected in the first two decades of the twentieth century and later during the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the fifties and sixties. The monuments are points of discord as they dishonor the Black and white soldiers who died for the Union, while they demean and disregard the humanity of Black people.

The monuments that sentimentalize Confederate heroes who lost the war convey the Lost Cause myth of the Confederacy, a narrative that romanticizes slavery as benevolent as it recalls Confederate soldiers as gallant and chivalrous, rebel leaders as saintly, the South solidly united against Northern aggression, and Reconstruction as corrupt. Above all, the Lost Cause myth is built on a belief in the superiority of the white race and the need to forcibly control and subjugate Black people.

Professor Adam Domby, an award-winning historian and specialist on the Civil War and Reconstruction, examines the role of lies and exaggeration in the Lost Cause narratives and their celebration of white supremacy in his timely and groundbreaking new book The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory (University of Virginia Press, 2020).

In his book, Professor Domby debunks the romantic Confederate myths by exposing the cruelty and barbarity of slavery; the ambivalence of many Confederate troops; the high rate of Confederate desertion; the extent of Union sympathizers in the South; the rise of Jim Crow; the brutal violence against Blacks; the monuments erected to intimidate Black citizens; the many lies about war service by white Southerners to claim veterans’ pensions; the myth of Black Confederates; and more.

Professor Domby’s book reveals that much of our understanding of the Civil War remains influenced by falsehoods of the Lost Cause, lies perpetuated in popular movies such as the silent classic The Birth of a Nation and the lavish Gone with the Wind. As a historian, he sees an obligation to share the reality of history and put to rest longtime falsehoods that were used to justify white supremacy, Jim Crow segregation, and the disenfranchisement and subjugation of African Americans.

Dr. Domby, an Assistant Professor at the College of Charleston, is an award-winning historian of the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the American South. In addition to Civil War memory, lies, and white supremacy, Professor Domby has written about prisoners of war, guerrilla warfare, Reconstruction, divided communities, and public history. He received his MA and PhD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill after receiving his BA from Yale University.

Professor Domby generously discussed his work and his writing by telephone from Charleston, South Carolina.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for speaking with me Professor Domby about your work as a historian and your new book, The False Cause, a debunking of myths about the Confederacy and the Lost Cause narrative.

I understand that you’re dealing with many media inquiries, and it must be somewhat surprising how newsworthy your book has become with the increasing focus on our history of racism since the brutal police murder of George Floyd in May. It seems many Americans are rethinking our fraught past as our president doubles down on his racist rhetoric.

Professor Adam Domby: Yes. I wrote the book knowing that the Lost Cause memory obviously still mattered. And I wanted the book out by the 2020 election in part because of the appeals to Confederate symbols.

I didn’t necessarily expect the president himself to be quite so blatant as he’s been. I also didn’t realize how many monuments were going to be suddenly removed. I knew the book was would be somewhat timely, but I did not expect to have at least one reporter calling me a day, if not more, for about a month this summer. I have talked to reporters before, but now it’s very busy, and it definitely caught me a little off guard.

I felt the book needed to be written because it relates to the present issues. The historical narratives that these monuments are supporting are fundamentally undergirding systemic racism. And, so long as we have these falsely propagated narratives of history, the harder it will be to dismantle systemic racism. I see it as the start of a longer process—of first correcting the historical narratives so that we can actually address the ramifications of what has happened historically.

Robin Lindley: You mention in the epilogue of your book that historians have a duty to question false narratives and myth, and you do a masterful and carefully documented, point-by-point, debunking of the Lost Cause narrative. How did you got involved in this project? Did you grow up in the South?

Professor Adam Domby: Yes. I was born and raised in Georgia. In fact, my childhood home was not far from where Sherman’s headquarters was during the siege of Atlanta. And I always had an interest in the Civil War. I saw the movie Gettysburg as a kid, and I followed other stories of the war.

But I went to college being a math major. I thought I would get a degree in math and that lasted all of one semester. I was fortunate that, on a whim, I took a class called “Wilderness and the North American Imagination” that was taught by Aaron Sachs, and I really liked this class. I picked another class that he was teaching, and that led me to eventually major in history. During college, I initially thought I’d be a colonial historian, but I fell in love with the Civil War again when I took a class with David Blight and started to see things that I had grown up learning in new ways.

I grew up in a region where the Confederacy was still often romanticized. So it was eye-opening for me to take a Civil War class and additional seminars on memory that presented a different view of the war.

I hadn’t decided yet to be a professional historian. I was going to be a park ranger. I worked as a park ranger for a while, and then left that, worked in politics for a bit, and then decided to attend graduate school. Even then, I didn’t think I’d write about Confederate monuments. I planned to write on prisoners of war. But, in my first year of grad school, I stumbled upon a document while working on a term paper, and that document sort of launched me on this process. The document was a [1913] dedication speech by Julian Carr for a Confederate monument [at the University of North Carolina].

I didn’t realize at the time how important that speech would be in shaping my own future. I thought this was an opportunity to teach people a little bit about Jim Crow. But I put it out there and activists took it and ran with it, really educating people about these monuments. I didn’t really think about social activism, and I didn’t fully appreciate yet the impact these monuments have on students and faculty of color who have to walk by them. That only came later. I saw this as a side project, maybe for some articles in the future.

I had two articles that I wanted to write. One was all about white supremacy and memory and the other was about lies and memory. And then I looked at those projects and it eventually dawned on me that this was actually the same project. The lies were part of the monuments and the white supremacy aspect was tied to the monuments and the Confederate fraud.

I arrived at the College of Charleston just after the Mother Emanuel terror attack here. And then the 2016 election of Donald Trump led me to put aside my dissertation project and focus full time on this project. This was a book I felt was important to have out there that would be useful to people who are having to engage neo-Confederates to show how this Lost Cause narrative was propagated and continues to be propagated. I think it has something both for the public and for other scholars.

Although it seems timely on some level, I did not realize how timely it would become, until it came out. I was actually worried it would come out too late. I really was hoping to have it out before the primary elections, but it turned out to be perfect timing.

Robin Lindley: You begin your book with a description of the Silent Sam monument and that speech of Julian Carr, who you researched. From your book, it seems that Carr was a grandiose conman who misled people about his background as he celebrated the Confederacy. What did this Silent Sam statue represent to him?

Professor Adam Domby: Silent Sam was a Confederate monument put up by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. It came up at the same time as all those Confederate monuments at city halls and courthouses. In fact, this statue at Chapel Hill is across the street from a courthouse and Post Office, so it’s central in the town. It was put up in 1913, and other colleges have similar monuments such as the University of Mississippi. Increasingly they’re being removed because they were put up at a time when the schools were segregated and there were no Black students at the time. Making Black students feel welcome was the opposite of what college leadership wanted to do at the time. These monuments were put up explicitly to celebrate white men and to teach white supremacy to the next generation.

The state’s future leaders and the next generation were being trained at UNC, according to Carr, and he wanted them to learn to be white supremacists. That’s basically what he said. And this monument was meant to celebrate the success of overturning Reconstruction. And something we often forget about the Lost Cause is that it wasn’t just about how we remember the war. It’s also about how we remember the antebellum era and how we remember the era after the war.

You might say the Lost Cause narrative includes history all the way to the present. It’s an evolving memory of course, but the memory that they wanted and still want.

Robin Lindley: How did Carr embrace the Lost Cause narrative?

Professor Adam Domby: The Carr speech was unremarkable at the time, despite the fact that he was saying that Silent Sam was a monument to white supremacy. His speech was so unremarkable that the newspapers did not carry any note of it other than that he gave a speech and he had given so many speeches before. They ran the governor’s speech and a few other speeches given that weekend, some of which also hinted at white supremacy, but the Carr speech was largely forgotten with a few exceptions because he’d given so many similar speeches. The only thing that stands out from this one was the statement he makes about his personal part. To Carr, this was a monument devoted to celebrating the overturning of gains that African Americans had made, and this was in the aftermath of the disenfranchisement of African-Americans. Carr wanted to celebrate that North Carolina was now a controlled by whites. He was helping create the solid South. It didn’t exist in 1876. It was created by disenfranchisement largely and aided by false narrative of history.

Robin Lindley: What would you like readers to know about the major aspects of the Lost Cause narrative?

Professor Adam Domby: The first is the denial of the cause of the war. Denying the central role of slavery is crucial for the Lost Cause myth because, if you fought a war for slavery, you were a loser. If you fought a war for states’ rights and it’s 1901 and state’s rights still exist and are constantly being cited as a reason why the federal government shouldn’t intervene in disenfranchisement, then you’re a victor. In fact, you can be celebrated by continuing the fight for segregation, and you were a hero for segregation as well. This was overtly making Confederate soldiers into white heroes of white supremacy while also stopping them from being the losers.

Lost Cause narratives also remember slavery as benevolent, while simultaneously remembering Reconstruction as a time of corrupt African-Americans and carpetbagger. The benevolent slavery aspect brings this idea that there were happy slaves. But slaves were actually brutally terrorized into labor. That is what slavery does. But in this false memory there was a time when the races got along, and everyone was happy before the war, and only the intervention of Northerners during Reconstruction caused poor race relations in the South. And by this narrative, disenfranchisement of African Americans can be seen as not the cause of race relations being strained but as the cure for it instead. To be clear, Reconstruction was also not a time of exceptional corruption.

Similarly, Confederate soldiers are remembered as the most heroic and devoted soldiers of all time who were only defeated due to overwhelming manpower. The problem with this, of course, is the high levels of desertion in North Carolina and other states.

The conduct of the war is another aspect of the Lost Cause that is often overlooked. How do we remember the conduct when we ignore racial massacres? Race and racism shaped every aspect of the war: how the war was fought and how that shaped Confederate strategy. So, with the Lost Cause, these Confederate soldiers are rewritten as noble men, despite what they fought for, how they fought, and that they in participated in racial massacres.

And, returning this narrative of history, the lie is not just used to remember Confederate soldiers well, but to justify Jim Crow as a system, to defend Jim Crow, and to support Jim Crow. To me, that’s the central key to this whole thing. All of these lies are holding up the biggest lie of all: that races are different in that one race is better than the other. That that’s the big lie at the top.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for that explanation Professor Domby. When I was in grade school and high school in late fifties and early sixties it seems that these myths were the view reflected in our history textbooks. I grew up in Spokane Washington, and our texts shared a romanticized view of the South and slavery, and stressed the failures of Reconstruction.

Professor Adam Domby: It’s a narrative that became the norm and was pushed very much. In the South, this Lost Cause version was appreciated as a way of defending the South from Northern intervention. That narrative of history allows you to also say that race relations in the South are a Southern issue. That’s the message of the Lost Cause. Whereas, if you have a more accurate version and you’re living in Washington, you might think, maybe we should intervene. Instead, this was all about convincing and exporting the views of the South to the North and West.

Robin Lindley: And also, I think, so publishers could sell the same books in the North and South. Your book is very timely. The president has been criticized by many for seeming to care more about these monuments to dead racists and traitors than he cares about living Americans.

Professor Adam Domby: Especially the lives of Black Americans. It’s worth pointing out whose lives he cares least about. It’s true that many Americans are dying right now due to Covid-19, but communities of color are impacted at much higher rates of infection and death.

He also ignores that police violence is similarly disproportionately borne by African Americans. And Trump is not a historical rarity. We see the same thing in Julian Carr’s language back in the early 20th century when Carr said, “lynching is bad but. . .” There should be no “but” at the end of the statement, because lynching is bad. We should be able to stop there, but he didn’t. He said lynching is bad but, until all white women feel safe themselves, we can’t even address it. For Julian Carr, the lives of Black men were less important than white women feeling comfortable. This seems reminiscent of Trump’s appeals to suburbia.

The statement Black Lives Matter is so important right now because historically Black lives had been viewed by those in power as less important than things like monuments and every white woman feeling entirely safe at all times.

We see something similar now with Trump as he focuses on monuments while ignoring the underlying meaning as a way of signaling either on purpose or not. But we’re seeing that signaling again and again, and the roots of that racism are not new.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for pointing out the meaning of Black Lives Matter. After all this time, some people are still confused. You mention in your book that, when many of us read about Southerners, we immediately think only of white men while ignoring most of the other people there, particularly the non-white people. I do that at times.

Professor Adam Domby: I’m guilty of that myself. I think we all are. I think you’d be hard pressed to find a history teacher in this country, even a historian of the South, who doesn’t occasionally mess that up when they’re in class or writing. When I finished the book, one of the last things I did was go through and check every time I used the word “Southerner” and I caught myself multiple times in that final rewrite where I said Southerner when I meant white Southerner. It’s short hand that we grew up with. That’s what happens when you live in a society that is built around systemic racism. You don’t realize you’re inviting it, so it requires conscious effort to avoid these mistakes.

Robin Lindley: What do you think should happen with the symbols of the Lost Cause such as the Confederate statues and monuments?

Professor Adam Domby: The first thing I would say is that my own views are constantly evolving. One of the things that I’ve learned by talking to colleagues and students who are Black is that I can’t fully appreciate the harm done by these symbols when they’re seen by a person of color or a Black person. The closest I can imagine, and this is not the same, is my visceral reaction when I see a swastika, and I’m of Jewish descent. Another historian of the South phrased it like this: So, when I see a Confederate monument, it doesn’t insult my personhood in what it says, but it insults my principles, which is a very different experience than if I were Black.

It’s important for us to realize the harm that these monuments do, and it’s very hard for a white person to appreciate it. A white person must listen and hear what harm is done by these monuments and what message these monuments represent, whether or not they believe that’s what the monuments were meant for. With symbols send messages, there’s always a subtext. The same goes for the Confederate flag. So I think that’s the first thing to remember.

The second thing to remember is that, when it comes to monuments, I don’t think I’m the most important person to ask. One of the things that I see is that these monuments were put up in an incredibly undemocratic fashion. I think that there isn’t anything wrong with allowing communities to decide what to do with them. If they decide they want to put them in a museum, that’s on them. If they decide they want to try contextualization, that’s on them. If they decide to pull the thing down and leave it broken in the park, that might be the best solution for them.

In some ways, I feel like my job is to give the context of the monuments that allows communities to decide what to do about it. I try usually to avoid giving an opinion about what to do with monuments, except when the monuments are in communities that I’ve lived in. That being said, I think that these monuments are tools of racial oppression at times, as when they stand in front of a courthouse. And so those are especially problematic, and I don’t think that they teach history.

Robin Lindley: And what should happen with the Confederate flag?

Professor Adam Domby: I think the Confederate flag has no place being put in front of schools or public buildings. It is a symbol that was from its creation designed to intimidate Black people and to celebrate white supremacy. From its earliest days, the flag was tied to white supremacy and that meaning has only grown over time. [Former Republican Governor] Nikki Haley liked to say that the symbol was appropriated. It wasn’t appropriated by white supremacists. It was already owned by them. It just became even more so.

It’s important for us to remember that fixing the narrative is the starting point to undoing systemic racism. It’s not the endpoint to take down the monuments, but it is also not just a symbolic act because it undermines the Lost Cause, which upholds white supremacy. It’s more than a symbolic act because having a democratic landscape that is welcoming to all impacts how the next generation learns about how to understand who’s worthy of admiration and what values we should emulate, and who we want to emulate. But it doesn’t solve the problems society faces.

Some political figures are perhaps hoping that, if we just remove the monument, the problem goes away. But the problem is still there. The problem is systemic racism. Getting rid of the monuments is a first step in being able to understand the sin of racism. And so long as you believe the Lost Cause, people will be able to claim with a straight face that systemic racism doesn’t exist.

You literally have Republican politicians right now saying that systemic racism is not a thing and that these monuments teach history and have nothing to do with slavery. So long as you have that message going forward, I don’t see this [monument removal] as solely symbolic action because the narrative they are upholding is both false and justifying white supremacy.

I would love to see a democratic process and see communities discuss and decide as a group where everyone has a say, but the reality of the situation is that Southern legislatures have made that nearly impossible. And so, perversely, what you have going on is that heritage acts are leading to the destruction of monuments because there is no democratic process. What do people do instead when all legal means are exhausted? There’s only one option: they resort to extra-legal means.

And the process has the potential also to be educational. I saw in Charleston over the last five years that the city has learned about the history of John C. Calhoun through debates, and that’s the history that wasn’t there when he was just a monument. In the process of removal, people were able to learn something. That being said, that it took five years is both upsetting and surprising. It should have been quicker perhaps but I am also a little surprised it didn’t take longer.

I would love to see our landscape be one that is welcoming to all. That is more important than using monuments to teach history. I thought for a long time, that Silent Sam and other statues had the potential to be a teaching tool. I could use them to teach about Jim Crow and white supremacy, and racial violence during Reconstruction. And I thought that for longer than I should have.

But I knew there was no going back when avowed white supremacists started showing up on the UNC campus to “protect” the monument. That’s when I had the realization that this monument was making students of color and myself feel unsafe. And I don’t need monuments to teach Jim Crow. I don’t even need a picture of them. I can talk about it. But I can’t teach about Jim Crow if my students and I can’t get to the classroom safely. And to me that moment meant long term there was no solution that kept the monument on campus.

The other key thing that led me to shift my views was talking to students and faculty of color and listening to them, hearing them say that they would take a different route when they’re going to Franklin Street [to avoid Silent Sam]. When they’re walking through campus, they avoid that part of campus. Why are they doing that? The monument was harmful because students need to feel welcome on their campus. A fundamental aspect of being open to learning is to feel safe. It’s very hard to learn when you don’t feel safe in that environment.

Robin Lindley: It’s impressive that you consulted with Black students and Black faculty members on the Silent Sam statue at UNC. Now, with the current climate and the president’s comments about race, people are learning more about history.

Professor Adam Domby: I am not sure it is impressive. It seems UNC should have been doing that all along and they still aren’t. I don’t know about learning history, but with the president’s overt appeals to racism, it’s become increasingly hard to deny racism as a problem in our society.

There were plenty of people in the Obama era who wanted to say that racism is solved. We have a Black president. You will not find people on the left saying that anymore, but you will find people on the right saying that and pushing white supremacist talking points at the exact same time. Some are very clearly lying and are very clearly dog whistling at times. I think there’s no question that, when the Trump administration does a lot of these actions, it’s a purposeful dog whistle and becoming a foghorn.

Trump went to Mount Rushmore [on July 4, 2020] and announced his plan for a garden of heroes not including a single Native American [at this sacred Native American site]. And, if you look at the language of that executive order explicitly, it says it includes American citizens at the time of the action. If you look at who’s considered an American citizen in the 19th century, Native Americans aren’t included. Legally speaking, you cannot include Sacajawea who would be an easy choice. She’s noncontroversial to whites as she helped white people; she’s nonthreatening

The idea that America is a white nation is embodied in that historical narrative that Trump’s pushing. You’ll also notice which African Americans are included. It’s always whoever is perceived by the right as safe, at least in memory if not in reality, You have MLK, but you don’t have Malcolm X. You have Frederick Douglas, but you don’t have W.E.B. Du Bois. You have Booker T. Washington instead. You have Frederick Douglas, but you don’t have Nat Turner. So, you have safe individuals. A lot of conservatives love to quote MLK and present themselves as being racially progressive.

Robin Lindley: And they ignore the last three years of Dr. King’s life when he talked about militarism, materialism, racism and economic injustice.

Professor Adam Domby. They also forgot what happened to him. He said all these great things, and then he got shot and killed.

When we look at these larger questions of monuments and memory, again and again what we’re seeing is that white supremacy is alive and well. And the narratives in history are being used to either signal or overtly state who belongs and who doesn’t, who’s included and who’s not. When Trump says we’re trying to celebrate our heritage, he’s not talking about the heritage of Native Americans or the heritage of Black Americans. He’s saying that heritage is about white Americans because it’s a concerted, exclusionary perspective. I think that his speechwriter, who presumably was Stephen Miller, did it on purpose. Even though he knew exactly what he was dealing with, he chose to not have a single Native American on that list. The surprise to me is Phil Sheridan and George Custer weren’t on there.

Robin Lindley: Yes, Custer didn’t make the final cut. Rev. William Barber recently mentioned that Trump focuses on statues but ignores issues of health care, education, economic inequality, and the cost of racism.

Professor Adam Domby: It’s a really important point that Barber made and it’s worth reiterating time and time again: no monument is worth more than a single life. I don’t care what the monument is to. I value the life of a human that’s living far more than I value any monument to someone who’s dead. The idea that you’re going to shoot someone for tagging a monument screams that the life of a dead individual from the past is worth more than a current life is very telling.

Robin Lindley: You stress the extreme violence against Blacks with the massacres of Black Union prisoners of war by Confederate troops during the Civil War, and the postwar lynching of Blacks by the KKK and violence of other vigilantes. How do these crimes and violence against Black Americans tie in with the Lost Cause narrative?

Professor Adam Domby: We see what the Lost Cause narratives tell us and who we’re supposed to celebrate. Why the police violence toward Black men and women is so much more than toward white men and women, has a long history.

I like to use the example of Nathan Bedford Forrest who grew up in a slave society and worked as a slave trader. He made a fortune off separating families and, to him, that was perfectly acceptable. It was more important to separate families than to keep families together. Let’s remember that he sold children away from their families because his bottom line was more important than their lives. When he saw an enslaved person who was out of line in his eyes, his immediate reaction was toward violence.

And it’s no surprise that, during the Civil War, when Forrest sees armed Black soldiers, his immediate reaction is to consider this a slave revolt. And that was the Confederacy’s reaction. Jefferson Davis orders said that when they saw Black troops, that was considered a slave revolt. So Forrest was directly involved in murdering Black prisoners of war because, for him, that was the appropriate response.

And then after the war, when you see African Americans asserting independence and not doing what Forrest wants, he joins in the Klan violence and passes that on to his grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest II, who became a head of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and was a Klan leader as well. What he learned growing up in that family was that the appropriate response to African-American asserting independence or being out of line was violence. Values get passed on another generation, not just by people saying you should be racist, but by observing what your father does and what your grandfather does and remembering how he’s celebrated after the fact. And Forrest is still celebrated, and so it’s no surprise. Then when we move forward to the 1960s, you have Bull Connor in Alabama thinking that violence is the appropriate response to Black children asserting that they had rights. We saw him use dogs and fire hoses and billy clubs. That is a historical legacy of a learned behavior: that a quick reaction with violence is the appropriate way to maintain order. Connor understood violence as how to maintain the status quo.

And so, it’s no surprise that today that police disproportionately shoot African Americans because they grew up in a society which was the society that Bull Connor came out of, which came out of the society that Nathan Bedford Forrest II came out of, and that Nathan Bedford Forrest came out of. And so, this is a long, drawn out process. You talk about fighting against white supremacy. This doesn’t end overnight. This is a process that will take generations. And, I’d love for us to be able to declare racism dead tomorrow, but I don’t foresee it.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for those powerful words Professor Domby. Have you read historian Professor Heather Cox Richardson’s new book, How the South Won the Civil War?

Professor Adam Domby: It’s a brilliant book There’s an old saying that the North won the war but the South won the peace. That is problematic. We must be clear. When we say the South won, what do we mean? We mean the white South, because Southerners also include Black legislators and governors and other as well. If you’re talking about South Carolina, for instance, the vast majority of South Carolina was supporting the Union because the vast majority of South Carolinians were enslaved.

Her book does a wonderful job explaining how we got to where we are today. I think it pairs quite nicely with my own book that looks at the underlying historical narratives of an ideology she studied.

And our books bring the history to the present, unlike some earlier histories. Bringing the past into the present is actually important right now in this moment where the Lost Cause is present and white supremacy has seen a form of resurgence. And the tie to the president is something that historians should address, in my opinion. Some may say that is too presentist or too political. But you can’t ignore the fact that all of our history writing has an agenda. We all choose to write on topics because we think they matter. Being more upfront about it is actually the best solution.

I appreciate that many books more recently directly tie into the present situation. I think there’s a growing sense among historians that the act of writing history is political and, in the act of teaching of history, the narrative we choose is a political decision. And, to pretend it’s not, is it in itself a political decision.

Robin Lindley: Thank you Professor Domby for your thoughtful and illuminating comments. And congratulations on your groundbreaking new book The False Cause on the myths of the Confederacy.