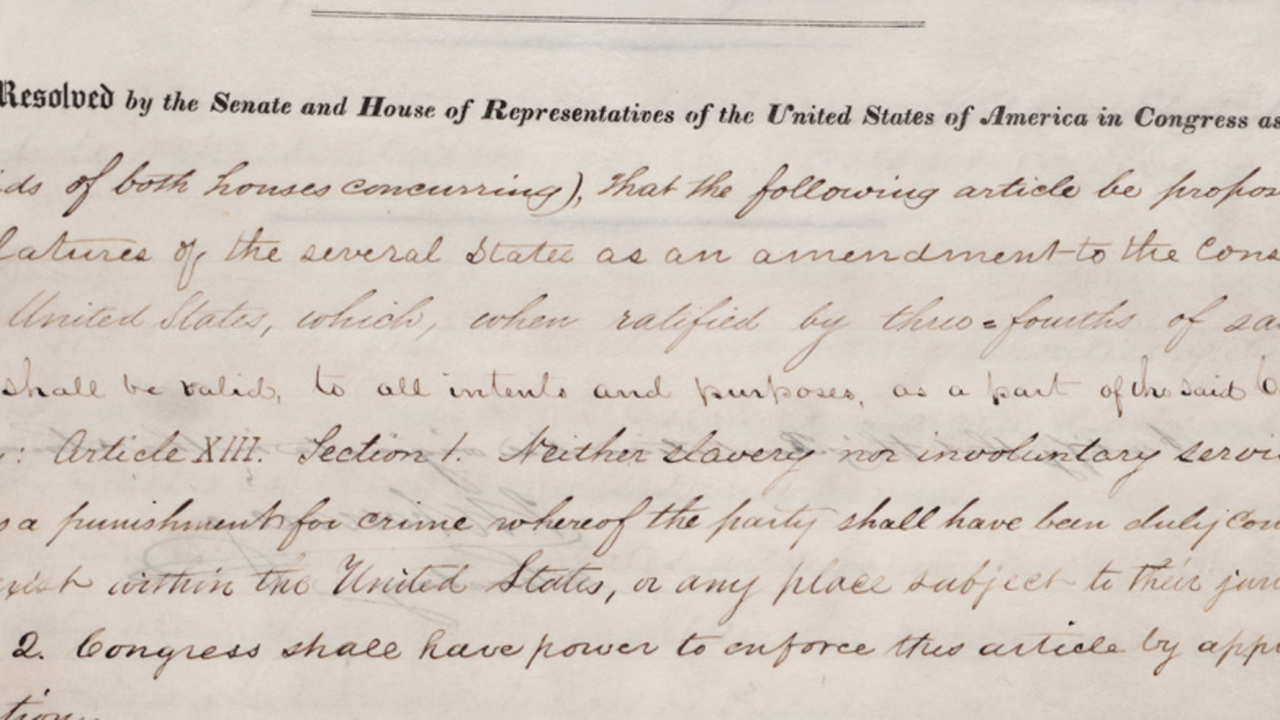

The joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified December 6, 1865, and abolished slavery, except as punishment for a crime. (National Archives via The Marshall Project)

This post originally appeared at The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the US criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

On Sept. 9, prisoners around the country staged a coordinated strike to mark the 45th anniversary of the bloody uprising at Attica prison in New York. According to strike organizers, more than 24,000 inmates in at least 12 states did not show up for work that day, and protests are ongoing in a handful of places. In Alabama, where the national strike originated, corrections officers joined the strike by not showing up to work this weekend, officials confirmed.

But most information about the strike is nearly impossible to confirm. Just as organizers have incentive to make the strike seem as effective as possible, so corrections officials want to play down the action and its impact. Officials in Alabama, Michigan and Florida confirmed work stoppages on Sept. 9. Prison officials in other states — including Texas and South Carolina, where The Marshall Project has received accounts of striking inmates — deny that any work stoppage or strike has taken place.

With the strike apparently winding down, here’s a primer on what happened and why.

How did the strike begin?

The strike was organized at Holman prison in Alabama, with a group of inmates who call themselves the Free Alabama Movement. Alabama’s prisons are consistently the most overcrowded and understaffed in the nation, according to a sweeping lawsuit filed this summer by the Southern Poverty Law Center. One expert witness in the suit told of “dangerous conditions, systemic mistreatment…as well as a crass disregard for their basic human dignity.” Members of the prisoner group have organized strikes before, and said that earlier this year they began building a network of other prison groups with similar aims, like one in Georgia that held a strike in 2010. Using a system of contraband cell phones, and with help from family members and organizers on the outside, “we decided we would use our labor as our leverage,” said Robert Earl Council, an inmate at Holman. “These systems are only here because of the money they’re making. The money we produce.”

Tensions reached a boiling point during the strike’s second week, when a correctional officer was stabbed to death by an inmate during a dispute over food. This fight was not directly related to the strike, but it drove correctional officers — also at risk when prisons are overcrowded and understaffed — to begin striking too. Email messages to the Alabama Correctional Organization, a guards’ union, were not returned.

What are strikers’ demands?

Strike organizers say they decided against issuing a single, unified list of demands, and instead chose to let each state prisoner group issue their own. They vary from state to state, but generally demand fair pay for their work, humane living conditions and better access to education and rehabilitation programs.

What happened during the strike?

The most common action was that inmates did not report for work. In one facility in Michigan, several hundred inmates staged a peaceful protest march in the yard, but after the march ended and the protesters returned to their units, chaos broke out, with several units being vandalized. In South Carolina, some inmates are organizing to stop paying the prison for goods and services like commissary items and phone calls. There were also reports of hunger strikes in several facilities.

The vast prison workforce

They’re not included in standard labor surveys or employment numbers, but at least half the nation’s 1.5 million prisoners have a job. Some states have a work requirement: any able-bodied prisoner must work or face disciplinary consequences. According to DATA1 from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, about 700,000 prisoners have daily jobs, helping to run a prison — mopping cellblock floors, mowing lawns, preparing and serving food. They act as GED tutors, they file papers in the chaplain’s office, and shelve books in the law library. A much smaller portion — an additional 60,000 inmates — participate in “correctional industries” programs designed to mimic real-world jobs; the federal prisons’ Unicor program, which had $472 million in net sales last year, is an example of these programs. An even smaller group (less than one percent of prisoners) work for free-world companies under the auspices of a federal program.

Despite the fact that prison workers meet many of the standard tests by which courts establish an employer-employee relationship, courts have consistently ruled that prison workers are not employees, and as such they’re not entitled to any of the protections that free-world workers take for granted: they are not free to leave a job if they choose; they don’t have access to worker’s compensation or disability pay in the event of an injury, and they’re not allowed to organize a union.

They also need not be paid minimum wage — or any wage at all. The average pay for a prisoner working a job in a state prison facility is 20 cents an hour. Unicor’s typical hourly wage is 23¢ to $1.15 per hour. Up to 80 percent of wages can be withheld for reasons like room and board and victims’ compensation. And in at least three states — Texas, Georgia and Arkansas — inmates work for no pay.

Forcing people to work without pay? Isn’t that unconstitutional?

Not if you’re a prisoner. The Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

Prison officials say work is necessary to prevent idleness and instill a work ethic. The wages can’t match those in the free world because prison workplaces have many inefficiencies and additional costs that free-world employers don’t: periodic lockdowns, daily counts, security costs. Beyond that, officials say they simply can’t afford to pay prisoners more. One 1993 GAO report said it would cost prisons “hundreds of millions of dollars more each year” to pay inmates minimum wage, and as a result, prisoner work programs would have to be cut or curtailed significantly (though this argument collides with the fact that someone has to cook the food and do the laundry).

One striking prisoner in South Carolina, told The Marshall Project that as part of a collective of jailhouse lawyers, he often hears from fellow inmates who received disciplinary infractions for not reporting to work when they were ill, but they have no legal recourse. “If the prison system says you have to work, you have to work. That is the Constitution,” he said. “They don’t have to pay you nothing. Why not? Because of the Thirteenth Amendment.” The inmate asked for anonymity for fear of retribution by prison authorities.

1DATA

This data was last collected in 2004, as part of BJS’s Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, and analyzed by the American Prospect.