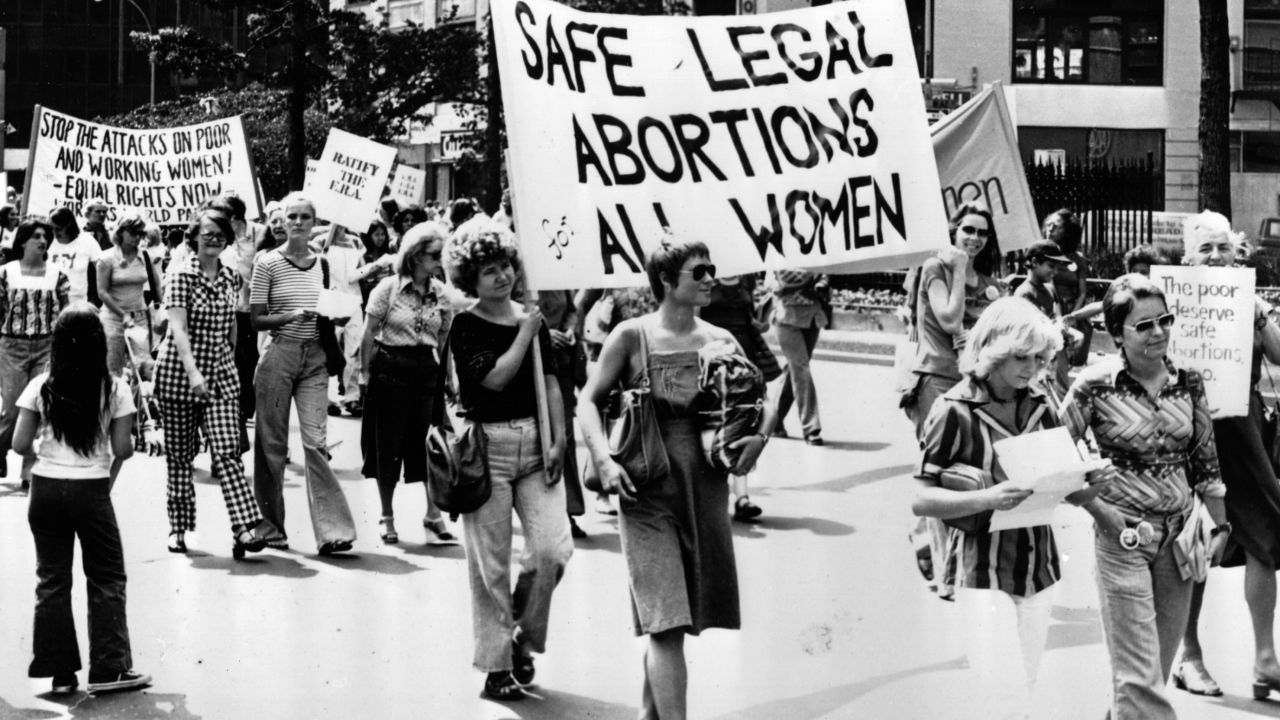

Women taking part in a demonstration in New York demanding safe legal abortions for all women. (Photo by Peter Keegan/Keystone/Getty Images)

I lived the first three and a half decades of my life in a world that for the vast majority of women today would be unimaginably brutal, like seeing a film in which a young girl is hanged by the neck until dead for stealing a loaf of bread. It was a time when desire or love could end your education, your ambitions, your bodily health, even your life – the years between when abortion was made illegal in the mid-19th century and when Roe v. Wade finally secured safe choice in 1973.

What happened when a teenager (and remember, contraception was hard to come by in those days if you weren’t married and in some states, even if you were), a young unmarried woman or a married women whose family could not support another child, what happened when any woman discovered she was pregnant and could not have the baby?

If she were affluent, she could fly to a place where abortion was available. For most women, this was not an option. If she could find one of the few real doctors who did abortions safely and if she could find some excuse to disappear for a couple of days, she’d be fine. But most women had no idea about doctors protected by local authorities and the mob or the Syndicate.

A pregnant woman could try to get her family doctor to help her, but she might be afraid to even mention the subject. Perhaps her family finding out meant she’d be forced to have the baby or be tossed out of the house. Perhaps that doctor would call the police. Even if he were willing [most doctors were male], if something went wrong, she’d be on her own. When I was helping women get illegal abortions in Chicago, I once had a graduate student hemorrhaging in my apartment. When I called her doctor, he said he had no such patient and hung up on me. If she died, I’d have gone to prison. I managed to pack her with ice and eventually staunch the bleeding.

Another friend was finally pregnant after almost giving up. But in her fifth month, she began miscarrying. When she went to the hospital, she was questioned for an hour while she was spasming and bleeding. Then she was left on a gurney in a hallway for hours, in intense pain and despair. No one did anything; rather she was treated as a criminal, since she might have aborted herself. She was devastated and the aftermath ended her marriage.

When I was in the 8th grade, a girl in my class was raped by four men in a local park. She became pregnant and was thrown out of school. She disappeared for months and when she came back to the neighborhood, she was gaunt and pale. The nuns took the baby, she said. She was considered totally disgraced. She never came back to school. Rape and incest were no reasons not to carry a baby to term. Nothing was.

Many myths circulated in high school, in college dorms and typing pools about how to get rid of an unwanted fetus. Few worked and several were dangerous, even life threatening, such as douching with Lysol. The other option was to find a back-alley abortionist or, failing that, to abort yourself with some tool. I aborted myself at 18 and almost bled to death. Afterward I was pale blue and weighed 80 pounds.

Back alley abortions were done without anesthetics and often in far from sterile conditions. The abortionist might be a doctor who’d lost his license, a midwife or a nurse — the luckiest possibility — or just someone making a buck on desperate women. You were generally alone with the abortionist, as abortion could get you sent to prison and the same fate hung over anyone helping you.

If you were having sex and not trying to get pregnant, every month when you expected your period was a time of high anxiety. Every time you went into your bathroom or a toilet stall, you hoped, you prayed for blood. If it wasn’t there, you felt doomed. Maybe you’d share that fear, or maybe there was no one you could trust. I cannot overemphasize how powerful that fear was, how it controlled you, how you could not escape it. Some women never had sex again.

Women died of botched abortions, as one of my closest friends did at 23. Some women, afraid to try to do it to themselves and unable to find help, killed themselves. But the death rate from botched abortions was higher than you’ve probably ever been told. Since it was considered shameful as well as a felony, kindly doctors wrote death certificates vague about cause of death. Stopped breathing was one.

No sexual freedom existed for women when we could not control our bodies, when love could kill us. Going back to those dark and violent times is the master plan of many in power today. If you don’t fight them, it’s intolerable how much suffering that will cause if the War Against Women is lost by feminists and our allies.

Abortion became legal not because justices one day woke up and changed their minds but because women took to the streets in huge demonstrations, spoke out on to what media we could, hired busses and harassed state and federal representatives. Because we fought until we won.

Watch Marge Piercy’s video: