Silent march on Father’s Day to end the NYPD's stop-and-frisk policy in New York City on June 17, 2012. (Photo: Alan Greig/flickr CC 2.0)

Donald Trump used the first presidential debate to press his case to implement nationwide the controversial police tactic known as stop-and-frisk, arguing that it had been an effective crime deterrent in New York City.

Under stop-and-frisk, police can stop and search any person they feel is behaving suspiciously, which includes “furtive movements” and “wearing clothing known to be associated with criminals.”

Trump hopes to solve inner-city violence by using the program, which during the presidential debate he claimed “worked very well” in New York City. It didn’t. (See more below the video.)

His push for nationwide stop-and-frisk is “consistent with his appeal to a racist populism that exists across America,” Khalil Gibran Muhammad, professor of history, race and public policy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, told BillMoyers.com.

Beyond appealing to his base, Muhammad says that by calling to expand stop-and-frisk, Trump is signaling that “the last four years of activism to reverse these policies… to take seriously the policy recommendations of Campaign Zero or Black Lives Matter more generally, will not happen under his watch.”

Trump is really saying we will go back to “business as usual” Muhammad says, “rather than changing course in the way that so many people have called for,” including President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. For over 100 years business as usual has meant targeting minorities through programs like stop-and-frisk as “an instrument for control,” Muhammad told Bill Moyers in 2012.

White communities would not “tolerate this kind of treatment” in the name of public safety, he added. “You couldn’t go into any East Side apartment or any West Side co-op anywhere in New York City [or Trump Tower!] and start asking 17-year-old white boys for ID when they were out in their pajamas.”

Watch the clip:

Trump has said “stop-and-frisk has had a tremendous impact on the safety of New York City. Tremendous beyond belief.” So tremendous that in 2013 a Manhattan federal court judge ruled stop-and-frisk, as practiced in New York City, unconstitutional.

In her ruling, Judge Shira Scheindlin found the NYPD practices overwhelmingly targeted minorities and violated their civil rights. She also appointed an outside monitor to overhaul the program.

Some of the facts on stop-and-frisk Scheindlin included in her ruling:

- Between January 2004 and June 2012, the NYPD conducted over 4.4 million stops. The number of stops per year rose sharply from 314,000 in 2004 to a high of nearly 686,000 in 2011.

- Fifty-two percent of all stops were followed by a protective frisk for weapons. A weapon was found after 1.5 percent of these frisks. In other words, in 98.5 percent of the 2.3 million frisks, no weapon was found.

- Of all the people stopped, 52 percent were black, 31 percent were Hispanic and 10 percent were white. In 2010, New York City’s resident population was roughly 23 percent black, 29 percent Hispanic and 33 percent white.

- Weapons were seized in 1.0 percent of the stops of blacks, 1.1 percent of the stops of Hispanics, and 1.4 percent of the stops of whites.

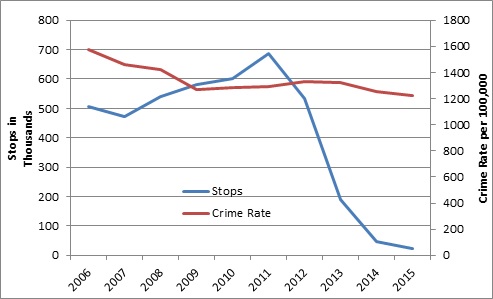

A recent analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice concluded that statistically there was no relationship between stop-and-frisk and crime rates. As the figure below shows, stop-and-frisk increased in 2006, when there were 500,000 stops citywide. After a high of nearly 686,000 stops in 2011, the number of stops began to fall, starting with 533,000 stops in 2012 until the program wound down, with about 23,000 stops in 2015. During that period, crime in general also decreased both when the number of stops went up and went down. If stop-and-frisk had a direct impact on crime, as Trump maintains, one would expect the crime rate to increase significantly when police reduced the number of stops. Instead, New York City has become safer.

Stops vs. Crime in NYC (2006-15)

(Source: NYCLU Stop-and-Frisk data and NYC Compstat)

In her ruling, Judge Scheindlin wrote that the stop-and-frisk program in New York City had exacted a “human toll” in demeaning and humiliating law-abiding citizens. Muhammad, author of The Condemnation of Blackness, describes stop-and-frisk, as it has been implemented in black communities, as an “everyday” practice that particularly affects “young people, aged 18 to 35, on their way to school, to work, to the corner bodega, to dance class, to after-school tutoring, to their grandparents’.”

On Trump’s call to expand the tactic nationwide, Muhammad says that in many ways stop-and-frisk is “already everywhere” — it’s just not formally implemented or hasn’t come under national scrutiny, as, for example, Ferguson did after the police shooting that killed Michael Brown. In 2015, a Justice Department civil rights investigation concluded the Ferguson police department and the city’s municipal court engaged in a “pattern and practice” of discrimination against African-Americans, targeting them disproportionately for traffic stops, use of force and jail sentences — and preyed on them financially to fill budget gaps.

“[W]e can no longer make any meaningful distinctions between what happens in Tulsa, Charlotte, Oakland, New Orleans, Philadelphia or Baltimore, precisely because police officers have been operating essentially from the same playbook,” Muhammad says.

Social Justice

Expanding law enforcement, as Chicago recently announced it will do by hiring nearly 1,000 more police officers, is not the type of solution that will help communities suffering from high rates of violence, says Muhammad. He points to the “abysmal” clearance rate — a measure of crimes solved by the police — in cities suffering from high murder rates, such as Chicago and Baltimore.

“More police officers are not likely to solve murder problems when people in the community are already feeling overwhelmed by abuse of policing,” Muhammad says.

Instead the conversation should switch away from a law and order response to a social justice response. “We don’t need criminal justice reforms, we need a new social justice system,” Muhammad says. He recalls the Progressive Era in the early 20th century, when working-class whites and immigrant criminals were treated sympathetically as victims of poverty and isolation.

Muhammad says he envisions the coordination of the state systems responsible for health, education, labor markets, transportation, energy and others to “coordinate in a way that takes criminal justice from being the frontline response to social calamity, inequality and suffering.”