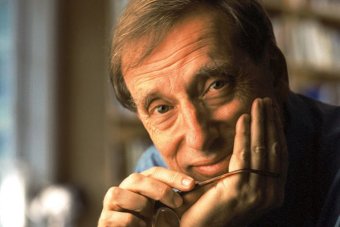

Herman Melville (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

This post originally appeared at The Nation.

Santiago de Chile may seem a strange place from which to try to understand Donald Trump and how to resist his most aberrant edicts and policies, and yet it is from the distance and serenity of this Southern Cone city, where my wife and I live part of the year, that I have found myself meditating on these issues, abetted by the insight and doubts of none other than Herman Melville.

When the Pinochet dictatorship forced me and my family into exile after the 1973 coup, the vast library we had laboriously built over the years (with funds we could scarcely spare) stayed behind. Part of it was lost or stolen, another part damaged by a flood, but a considerable part was salvaged when we went back to Chile after democracy was restored in 1990. What strikes me about these books that have withstood water and theft and tyranny is how they enchantingly return me to the person I once was, the person I dreamt I would be, the young man who wanted to devour the universe by gorging on volume after volume of fiction, philosophy, science, history, poetry, plays.

Simultaneously, of course, those texts, mostly classic and canonical, force me to measure how much desolate and wise time has passed since my first experience with them, how much I myself have changed, and with me the wide world I traveled during our decades of banishment, a change that becomes manifest as soon as I pick up any of those primal books and reread it from the inevitable perspective of today.

It is a happy coincidence that the works I have chosen to revisit on this occasion are by Melville, as I can think of no other American author who can so inform the perilous moment we are currently living. Roaming my eyes on shelf after shelf, I soon lit upon his enigmatic novel The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade, and sandwiched between it and Moby Dick, a collection of his three novellas, Benito Cereno; Bartleby, the Scrivener; and Billy Budd, Sailor.

Having just participated, as an American citizen, in the recent election that elevated to the presidency an archetypal liar and devious impostor who has hoodwinked and mesmerized his way into power, The Confidence-Man seemed like an appropriate place to start. Though it was published 160 years ago, on April Fool’s Day, 1857, Melville could have been presciently forecasting today’s America when he imagined his country as a Mississippi steamer (ironically called the Fidèle) filled with “a flock of fools, under this captain of fools, in this ship of fools!”

The passengers of that boat are systematically bilked by a devilish protagonist who constantly shifts his identity, changing names and shapes and schemes, while each successive ambiguous incarnation tries out one scam after another, swindles and snake-oil trickery that were recognizable in his day — and, alas, in ours. Fraudulent real estate deals and bankruptcies, spurious lies disguised as moralistic truths, grandiose charitable undertakings that never materialize, financial hustles and deceptions, bombastic appeals to the honesty of the suckers while showing no honor whatsoever — it all sounds like a primer for Trump and his buffoonish 21st-century antics and “truthful hyperbole.”

Of course, Melville’s time was not the age of Twitter and Instagram and short attention spans, so his ever-fluctuating rascal engages in endless metaphysical discussions about mankind, quoting Plato, Tacitus and St. Augustine, along with many a book that Trump has probably never even heard of. And rather than a bully and a braggart, this 19th-century pretender is garrulous and genial. But just like Trump, he displays an arsenal of false premises and promises to dazzle and befuddle his victims with absurd and inconsistent projects that seem workable until, that is, they are more closely examined — and then, when cornered by demands that he provide proof of his ventures, the scamp somehow manages to distract his audience and squirm away. And also like Trump, he exercises on his dupes “the power of persuasive fascination, the power of holding another creature by the button of the eye,” which allows him to mercilessly best his many antagonists, exploiting their ignorance, naïveté, and, above all, greed.

Indeed, Melville’s misanthropic allegory often seems less a denunciation of the glib and slippery trickster than a bitter indictment of those gullible enough to let themselves be cheated. The author saw the United States, diseased with false innocence and a ravenous desire for getting rich, heading toward Apocalypse — specifically, the Civil War that was a scant four years away. Fearful that, behind the masquerade of virtue and godliness performed by the role-playing passengers, there lurk shadows of darkness and malignancy, he was intent on revealing how the excessive “confidence” in America’s integrity, virtuousness and “ardently bright view of life” can lead to tragedy.

And the novel ends in a quietly terrifying way. As the light of the last lamp expires and a sick old man, one final quarry of the Confidence Man, is “kindly” led toward extinction, the narrator leaves us with this disturbing forecast: “Something further may follow of this masquerade.”

Those words pester me, because the “something further” that we are living today is a grievous circumstance that Melville could not have anticipated: What if somebody like the slick confidence man were to take power, become the captain of that ship of fools — in other words, what if someone, through his ability to delude vast contingents, were to assume control of the republic and, like mad Ahab, pursue the object of his hatred into the depths (in Trump’s sea there are many white whales and quite a few minor fish) and doom us all to drown along with him?

If Melville was not concerned with the possibility that his confidence man might become a demented, uncivil president, he did bequeath us, nevertheless, three short masterpieces where the protagonists rebel, each in their own special way, against an inhumane and oppressive system. By reading once again the novellas Bartleby, Billy Budd and Benito Cereno, I hoped, therefore, to discover what guidance Melville might provide those of us who ponder how to fight the authoritarian proclivities that Trump and his gang epitomize as they seek total and uncontested power to radically remake America.

I began, obviously, with Bartleby, the Scrivener.

“I would prefer not to”: Those are the emblematic words with which the protagonist, a copyist for a Wall Street lawyer (who is also the bewildered narrator of the tale), invariably responds when asked to perform the most minimal tasks but also when offered a chance to better or protect himself, to the point of losing his job, his housing and, eventually, his life, as he ends up starving his body to death in prison. When I first read this novella in my youth, I saw it, not incorrectly, as an allegory about Melville himself. At the time it was published — in 1856, just before the experimental and uncompromising The Confidence-Man came out — the author (whose Moby Dick had sold poorly and been, in general, misunderstood when it appeared in 1851) was struggling with his own refusal to accommodate his style and vision to the commercial literature of his age, a refusal that corresponded with my own 1960s ideas about not selling out to the “establishment.” Though I was able to grasp, as many readers have since Bartleby first appeared, that this radical rejection of the status quo went far beyond a defense of artistic freedom, delving into mankind’s existential loneliness in a Godless universe, it is only now, beleaguered with the multiple dangers and dilemmas that Trump’s authoritarianism poses, that I can fully appraise the potential political dimensions of Bartleby’s embrace of negativity as a weapon of resistance.

Not because his ascetic withdrawal, passivity, and “pallid hopelessness” are what the majority of Americans who voted against Trump need in these times of bellicose regression. It is, rather, the specific way in which the protagonist posits his rebellion that may serve as a model for those of us who feel threatened by the aggressiveness of this president, who, like Ahab, is “possessed by all the fallen angels.” What disarms, indeed leaves Bartleby’s employer “unmanned,” is that the scrivener’s responses are unwaveringly mild, “with no uneasiness, anger, impatience or impertinence.” Bartleby’s individual intransigence was insufficient to change the disheartening world in Melville’s time, but it is a great place from where to start an active resistance in ours.

Imagine “I would prefer not to” as a rallying cry. Sanctuary cities and churches: “I would prefer not to help hunt down undocumented men, women and children.” Indigenous tribes and veterans and activists: “I would prefer not to step aside when the tanks and the pipelines roll in.” Civil servants at federal agencies: “I would prefer not to enact orders to destroy the environment, eviscerate the public school system, deregulate the banks, devastate the arts, attack the press; I would prefer not to cooperate with unjust, misguided, stupid, contradictory executive orders; I would prefer not to remain silent when I witness illegal acts that violate the Constitution,” and on and on we could go, on and on we must go, if we are to be free. If every opponent of Trump were to adopt this stubborn and placid refusal to go along — each deed of collective defiance always begins with somebody individually saying “No!” — our belligerent president would find it difficult to impose his will, though we should expect a great deal of executive pressure against and persecution of those who stand in his way. Indeed, there are far too many signs already that dissidence, criticism, recalcitrance, whistleblowing and protests will be met with the full force of the state.

Whether that repression manages to control those who challenge Trump on multiple levels will not only depend on the obduracy and cunning of the president’s adversaries, but also on how the judiciary intervenes in this battle. How justice is served and, indeed, interpreted, will determine whether the orders of a fraudulent occupier of the executive branch can be contained.

It was thus natural to plunge next into the most distressing of Melville’s works, the last one he ever wrote (it remained unfinished at his death in 1891), the haunting and haunted Billy Budd. The title character is a sailor, conscripted into the British navy, who never thinks of using the words “I would prefer not to,” but on the contrary is agreeable and compliant. An angelic being, almost divinely handsome, able to lighten each day’s burden with his good cheer, popular among the crew and the officers, Baby Budd, as he is called, is an innocent lamb of a man loved by everybody on board the Bellipotent. Well, not everybody — precisely this wholesome harmlessness and beauty create in Claggart, the master-at-arms of the ship, a hatred, rage and envy, an “unreciprocated malice” that Melville attributes to sheer depravity and unfathomable evil. Given that Claggart is in charge of policing, discipline and surveillance, he has at his disposal an arsenal of means to trap Billy, deceitfully accusing him of conspiring in a mutiny, at a time when the British navy had been wracked with widespread revolts by sailors. When confronted with this indictment, Billy — afflicted by a “convulsed tongue-tie” incapacity to speak out when he is under extreme emotional stress — responds by striking Claggart. The blow kills the satanic master-at-arms — and Billy must face trial in front of a hastily convened drumhead court.

The administration (or mismanagement) of justice that follows is the crux (I use the word deliberately, as we will witness a crucifixion) of the story. Melville goes out of his way to praise Captain Vere, the commander of the ship: He is well-read, fair, brave, often dreamy, eminently honorable and has a sincere fatherly affection for Billy Budd, intending to promote him. And he does not doubt that Claggart (for whom he feels “a repellent distaste”) is lying, nor that his victim knows nothing of any conspiracy or harbors a single mutinous thought, and yet, Vere’s reaction to the homicide is peremptory:

“He vehemently exclaimed, ‘Struck dead by an angel of God! Yet the angel must hang!’ ”

Having thus passed judgment on Billy Budd, Vere will manipulate his court of junior officers (all dependent on him and under his authority) to declare the sailor guilty, without allowing for palliating circumstances or for the matter to be referred, as naval practice and law demand, to the admiral for adjudication. In order to get the verdict he desires — fearing that compassion and flexibility might encourage disorder and sedition — he must ignore his private conscience and yield to the imperial code of war and argue against a “warm heart,” which he calls “the feminine in man” and thus must be distrusted and “ruled out.” This failure of the father figure to protect the weak is a tragedy not only for Captain Vere (who will die in battle not long after this incident, with Billy Budd’s name on his lips as he agonizes) and for the blameless handsome sailor (who dies blessing the captain who has wronged him), but for humanity itself in its journey toward redemption.

If Melville is concerned with the miscarriage of justice (and one can only hope that the US courts will differ from Captain Vere by shielding those who are unable to defend themselves from malignant attacks and overreach by the government), his novella also probes another disquieting matter that obsessed him all through his life: the question and legitimacy of violence.

Violence comes in many guises and varieties in Billy Budd. There is, of course, the violence of the state, which Captain Vere incarnates and exercises with “full force of arms.” And then there is the violence of Claggart, the official enforcer of order who abuses his power and becomes an instrument of perfidy and immorality. But most interesting is Billy Budd himself. Why does the angel deliver the lethal blow that will annihilate him? He speaks with his fists when his tongue and throat are struck dumb by an assault upon the core of his being so wicked that he could not foretell it. Indeed, it is his extreme good nature, his unwillingness to recognize evil—despite having been warned that Claggart, with “his small weasel eyes,” is out to get him — that leaves him unprepared. One could almost venture that our ill-fated hero has too much trust and “confidence” in his fellows.

Melville had already explored these issues of innocence and violence in Moby Dick — where the crew and officers are unable to stop the crazed skipper of the Pequod from driving them all to ruination (all, that is, save the narrator, who wants to be called Ishmael) — but it can be argued that nowhere did he delve deeper into those predicaments than in Benito Cereno, serialized in a magazine in 1855 and revised when it was published as part of Piazza Tales in 1856 (again, just before The Confidence-Man appeared).

This traumatic story is centered on an astounding event at sea that actually happened, as I vaguely recalled as I opened the book, off the coast of southern Chile, a few hundred miles from where I was now re-reading it. A group of slaves — the year was 1805 — took over a Spanish vessel, killed most of its white crew and passengers, and demanded that the captain, Benito Cereno, return them to Africa. Melville moves the date to 1799 and rebaptizes the ship the San Dominick in order to more closely parallel the successful — and extremely ferocious — slave insurrection against the French on the isle of Saint-Domingue that would lead to the establishment of Haiti, the first black republic in the world. He is basically saying to his unheeding American public: This bloodletting awaits us if we do not end slavery.

What is extraordinary about Benito Cereno is that Melville has chosen to oppose slavery not by staging, as in Uncle Tom’s Cabin or so many abolitionist tracts and memoirs of the day, the cruelty and viciousness of those who hold other humans in bondage but rather by dramatizing how, when those slaves seek liberation through the only fierce means available to them, they will imitate their masters, use the same fear and torment that was imposed upon them to make sure that their former overlords do not dare to rebel. But that is not all: Melville presents this dire reversal of roles through the eyes of Amasa Delano, a well-meaning and decent American captain who, having generously sailed to the rescue, is duped by the masquerade that the slaves have forced the surviving whites on board to perform: that the ship has succumbed to a series of misfortunes (hurricanes, illnesses, adverse winds), that have left most of the whites on board dead and most of the blacks alive and wandering the deck helplessly, the eternal social order intact. Filled with racial prejudices, Amasa is unable to conceive that not only have the slaves broken out of what he considers their natural state of submission and submissiveness but that they have the subtlety and intelligence to create such an intricate plot. His blindness to the possibility of evil (the evil that is slavery and how that evil can also infect the slaves themselves) derives from his blindness to his own complicity in that evil, his failure to distinguish shadows from light, appearance from reality.

Amasa Delano joins a long list of Melville’s male protagonists (there is hardly a spirit-lifting woman or a child in his bleak tales) who are contaminated by innocence, who do not understand that, as a character in The Confidence-Man says, “nobody knows who anybody is” in a world that is a “painted décor,” where the worst of us hide their vilest appetites and sins under a veneer of nobility and the best of us are oblivious to the depths and spirals of that villainy. Melville’s heroes can be fooled because they are fooling themselves. It is the case of Billy Budd, who does not wish to even consider what Claggart is up to. It is the Wall Street lawyer, oblivious to how his style of life and aspirations are ultimately responsible for Bartleby’s refusal to cooperate. It is Benito Cereno, who never realized that the cargo of slaves he was carrying could spell his doom. It is Captain Vere, who suppresses the feminine in his heart in favor of the law of war without realizing that a few days later he will die in that war, that he has killed himself by hanging Billy. It is the case of the predestined company of the Pequod. There is no dearth of tenderness or affection, no lack of humor and intimations of hope in Melville’s parables — and he glories in the wonders of storytelling — but his basic message to America (and the world) is to wake up.

Reading these cautionary chronicles in the light of today’s disastrous Trump ascendancy, what struck me most was how so many Americans were unmindful, as Melville’s characters are, as to what the future would bring, the collective incapacity (and I include many of Trump’s supporters) to imagine, like Billy Budd, that such malice and trickery exist. And I admit that I shared the presumption that there were enough decent and good-willed white people in the United States to stop the lowest moral citizen in the land from capturing the highest political office, the most powerful on the planet. A sin of optimism: America is too good, too exceptional, too wonderful a country to commit that sort of fatal mistake.

Risky as it may be to extrapolate and extract prophetic words about the future from an author long dead, I might warrant that Melville would thunder: You fools. Fools, those who believed and continue to believe in Trump despite all evidence that he has conned you. And fools, those who thought it could not happen here and did not fully measure the rage and inhumanity blighting America since its inception. And more fools, all of you, to think it might get better than worse as the deranged days rush by, deluding yourselves that the institutions that have provided checks and balances through so many calamities will stand this test.

Wake up. Claggart is plotting and waiting in the wings. A dictatorship is far from impossible.

If it’s any consolation, America is not alone in its blindness.

I started rereading Melville in Chile animated by the expectation that my distance from the United States would help me to see how this author could illuminate the America of today and tomorrow, but to my surprise, as I advanced into his fictional universes, I had to admit that the frailties he was exposing and the quandaries he was scrutinizing could be applied to the country where my reading was taking place, a country whose long struggle for equality and justice, culminating in the peaceful 1970 revolution of Salvador Allende, had been sadistically suppressed.

Chileans back then nursed the illusion that our democracy was stable and enduring, only to be inconsolably awakened by the military coup of 1973, becoming aware, when it was too late, of the fragility of our institutions. How quickly so many of our people succumbed to demagoguery and brutality, how easily they normalized the everyday malice of dictatorship as they fell under the spell of consumerism.

But I also recognized in Melville’s masterpieces the very forms of resistance that many of us contemplated during those seventeen years of tyranny. Confronted with regression, shattered by grief, abandoned by the judges who were too craven and cowardly to defy the despotism of Gen. Pinochet and his oligarchical civilian acolytes, we had to choose between the armed rebellion of the slaves on the San Dominick or the “I would prefer not to” of Bartleby. Though there were some — a small group — among the military’s challengers who embraced violence against such a nefarious regime as righteous and the only path to victory, the enormous majority of the democratic opposition were wary of this insurrectionary strategy. It was a tactic destined to fail, we thought — and we were wary of the consequences of that violence, even in the unlikely case that it could be successful rather than counterproductive. History had taught us the same lesson that Melville had presaged in Benito Cereno: Far too often have the revolutionaries of today become the oppressors of tomorrow, repeating the mistakes and coercion of yesterday. And so, with the infinite patience of an Ishmael and the insubordination of a Bartleby and the angelic resolution of a Billy Budd, we vanquished the Claggarts of Chile.

Would the American people be able to do something similar?

Melville might say, I presume, that it cannot be done without a drastic ethical transformation of the country, the recognition that Trump is the mere excrescence of America’s dark soul. Our author would point out that what now plagues us are the sins of the past coming home to roost: America’s tolerance of bigotry and racism, America’s optimistic blindness to its own faults, America’s love affair with bogus spectacle and masquerades, America’s culpable innocence amid imperial expansion. The confidence man — and men — will continue to triumph until the citizens — or enough of them — take responsibility for having helped to create a land where Trump’s victory was not only feasible but, at some point, almost inevitable, a nation where so many Americans felt so alienated and abandoned that they willingly embarked on the “ship of fools.”

Of course, Melville wrote at a time when the submerged voices of humanity were hardly able to make themselves heard. So many of his protagonists are either rendered speechless in moments of crisis, like Billy Budd, or remain mute, like the slaves on the San Dominick, while their story is told and twisted by someone else, someone more powerful. Even Bartleby cannot rationalize or articulate why he rebels. And, except for the narrator, none of the sailors and officers of the multiethnic Pequod survive to tell the tale of the White Whale. Melville saw his blasphemous literature as providing an alternate version to the official “truth” of dominant history.

Today things are different. The voices of those who will and must engage in civil disobedience are anything but silent as they try to avoid the impending catastrophe.

And so, when I wonder if Melville’s fellow countrymen and women will be able to withstand the onslaught of the confidence man’s presidency, when I ask myself if the best of the American people will find the strength and cunning to force those in power to listen, when I try to imagine what sort of land the future holds, I leave the answer to that great ally of ours from the past, our eternal Melville. Here is how I prefer — yes, prefer — to envision that tomorrow where “something further may follow of this Masquerade,” describing it with some magical words culled from Moby Dick: “It is not down in any map: true places never are.”

Or better still: “I try all things, I achieve what I can.”