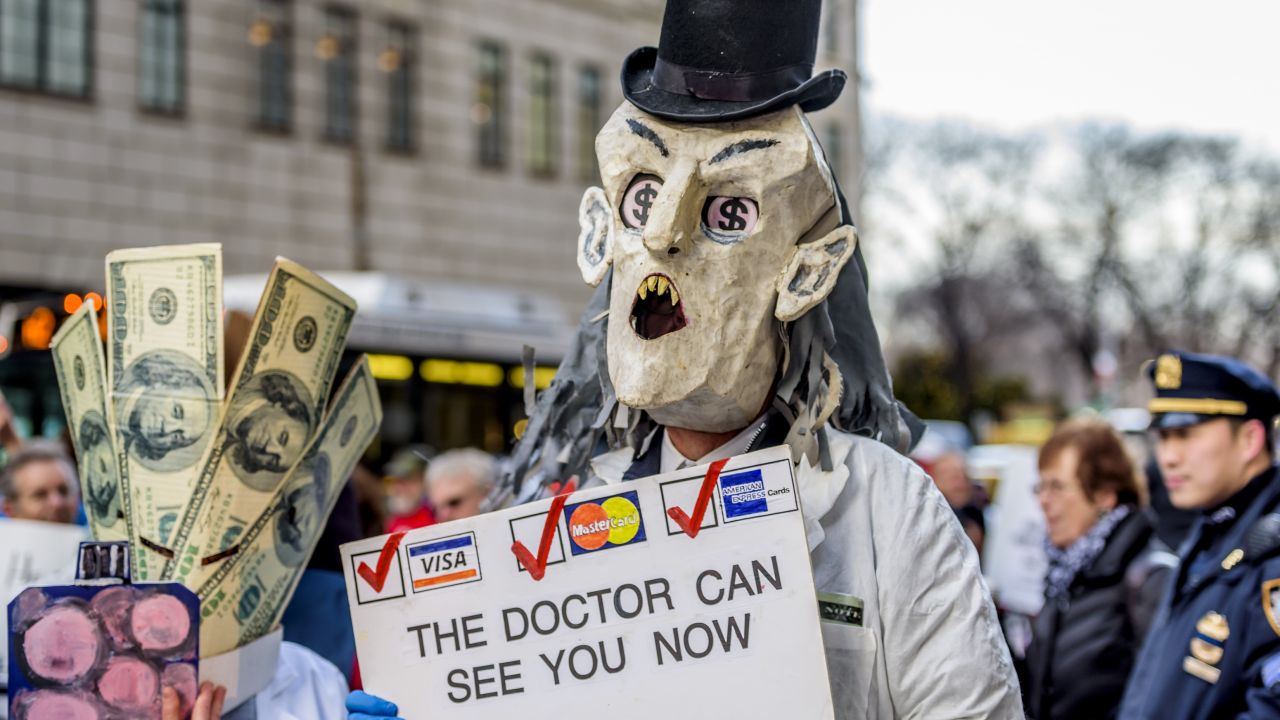

Outside Trump Tower in New York, health care justice advocates and other grass roots groups gathered to demand that Trump not to repeal the Affordable Care Act. (Photo by Erik McGregor/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at The Nation.

At the 100-day mark of the Trump administration, progressives have a lot to cheer: The movement moment that preceded the 2016 election proved not only durable but adaptable to a new political reality. We chanted “No ban, no wall,” and despite Trump’s bluster, he has failed to erect either barrier thus far. This is what democracy looks like.

But as we move past the initial months of this presidency — defined by far-right provocation and mainstream outrage — we enter the truly dangerous and far more challenging stretch of the Trump era.

Under the guidance of provocateur in chief Steve Bannon, this White House has offered Americans a series of clear moral choices, and the vast majority of us have reacted as could be expected: Trump’s early approval ratings are among the lowest in US history. But that consensus won’t be as easily won in the debates that lie ahead. The country will still face stark moral questions, but answering them will require an understanding of morality that has been neglected in American politics for decades.

Just weeks into Trump’s presidency, Sen. John Thune of South Dakota spoke plainly when asked about the Republican leadership’s strategy for the next four years. “He’s going to say things on a daily basis that we’re not going to like,” Thune told The New York Times regarding whatever scandal Trump had instigated that day. But “the broad legislative agenda and goals that we have…those would be big wins.”

They would indeed, and the cabal of white men who have been trying for decades to unravel the social safety net, undermine democracy and grant corporations unfettered power over our economy are as steady and determined as Trump is unpredictable. For example, while many of us were cheering the signs of Bannon’s waning influence in recent weeks, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the Justice Department’s intention to return the War on Drugs to its Reagan-era pitch, thereby reopening the federal spigot for prison construction and police militarization.

So Thune’s crowd will exploit today’s chaos to move their very old and familiar agenda forward. And the applause that followed Trump’s bombing of Syria is a sign of how well that strategy could work. The pundits and Democrats who howled at Trump’s refusal to help child refugees escape war lost their moral compass when it came to escalating that same war. There is now a consensus that the Bannon wing of the White House is too extreme. But will there be similar outrage when the victims and villains are less obvious than they have been in recent months? What happens when our norms and values are tested not by open provocation, but by the steady manipulation of government into a cudgel against the poor?

The challenges are perhaps most clear when we consider the fight over health care. President Trump and House Speaker Paul Ryan have failed spectacularly in their efforts to repeal Obamacare. That’s in no small part thanks to loud constituent opposition; some of us are feeling so triumphant that we are talking again about single-payer. And why not? We must name the real goal.

But meanwhile, the actual fight over Obamacare — the only health-care access that millions of people have right now — is regulatory, not legislative. I’ve written many times that the Affordable Care Act is best understood as an antipoverty program. In addition to providing tax credits to cover premiums and expanding Medicaid eligibility, thus growing that program by an estimated 11.2 million people, the ACA offers an indirect cash subsidy to 7.1 million people, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. About 58 percent of those who have chosen a plan through the ACA marketplace this year will receive a discount on cost-sharing, such as deductibles and co-pays. These subsidies, offered by insurers but financed by federal dollars, go to people making under 250 percent of the current poverty level. Despite our political obsession with the higher-income people in the individual-insurance market, such low-income households constitute the vast majority of Obamacare enrollees. This is precisely why Ryan and his ilk can’t tolerate the law: They rightly see it as an expansion of the Great Society they are dedicated to dismantling.

And so the administration has already started to dismantle Obamacare through changes in regulation. In mid-April, the White House finalized new rules that are designed to shrink the ACA’s insurance marketplace over the next year, cutting the enrollment period roughly in half and making it far more difficult to sign up via special enrollment. Trump has also threatened to cut the federal payments to insurers that finance subsidies for low- income households. These regulations echo the enrollment changes that the Republicans want for Medicaid — indeed, whatever the fate of Ryan’s American Health Care Act, we can be sure that the goal of “reforming” Medicaid in the much same way that Republicans and Democrats colluded to end welfare will remain a priority.

Obamacare’s quiet political weapon has always been time. If it were kept going long enough, too many people would be benefiting from the ACA for it to be killed, and states holding out against Medicaid expansion would no longer be able to bear the financial pain of doing so. But Trump and Ryan can now adopt a similarly patient approach toward destroying the system. They can suffocate the ACA using the same tool of government regulation that they claim to hate. But, of course, it’s only laws that help poor people that they really oppose.

Obamacare was never a perfect system; even at its best, it’s a market solution to a human-rights problem. We need a single-payer health-care system. But getting there requires a moral argument we rarely hear: that widespread poverty in a nation as wealthy as ours is a crime against humanity. To truly fight the Trump era’s extremism, we have to build consensus on this moral truth, too.