BILL MOYERS:

This week on Moyers & Company, the Internet as we know it: going, going, gone. I hope you’ll join us.

ANNOUNCER:

Funding is provided by:

Anne Gumowitz, encouraging the renewal of democracy.

Carnegie Corporation of New York, celebrating 100 years of philanthropy, and committed to doing real and permanent good in the world.

The Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the front lines of social change worldwide.

The Herb Alpert Foundation, supporting organizations whose mission is to promote compassion and creativity in our society.

The John D. And Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, committed to building a more just, verdant, and peaceful world. More information at Macfound.org.

Park Foundation, dedicated to heightening public awareness of critical issues.

The Kohlberg Foundation.

Barbara G. Fleischman.

And by our sole corporate sponsor, Mutual of America, designing customized individual and group retirement products. That’s why we’re your retirement company.

BILL MOYERS:

Welcome. If I told you that sovereign powers were about to put a toll booth on the street that leads from your house to the nearest Interstate, allowing your richest neighbors to buy their way to the open road while you were sent to the slow lane, you would no doubt be outraged. Well, prepare to scream bloody murder, because something like that could be happening to the Internet.

Yes, the Internet -- your Internet. Our Internet. The electronic public square that ostensibly allows everyone an equal chance to be heard. This democratic highway to cyberspace has thrived on the idea of "Net neutrality” -- that the Internet should be available to all without preferential treatment. Without preferential treatment. But Net neutrality is now at risk. And from its supposed guardian, the Federal Communications Commission. The FCC chairman Tom Wheeler is circulating potential new rules that reportedly would allow Internet service providers to charge higher fees for faster access, so the big companies like Verizon and Comcast could hustle more money from those who can afford to buy a place in the fast lane. Everyone else -- nonprofit groups, startups, the smaller, independent content creators, and everyday users – move to the rear. The Net, neutral no more.

A final decision on the new rules isn’t expected until later this year. Meanwhile, you have the chance to be heard during an official "comment period." We'll tell you more about that later in the broadcast, but first let's listen to two people who monitor this world and strive to explain it to the rest of us. Susan Crawford is a visiting professor at Harvard Law School, a contributor to Bloomberg View and author of this essential book, “Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age.”

David Carr covers the busy intersection of media with business, government and culture, and he writes a popular weekly column, “Media Equation,” for “The New York Times.” Welcome to you both. So help us sort out why the average citizen out there should care about this issue.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

Right now, for most Americans, they have no choice for all the information, data, entertainment coming through their house, other than their local cable monopoly. And here, we have a situation where that monopoly potentially can pick and choose winners and losers, decide what you see. How interesting, how interactive it is. How quickly it reaches you, and charge whatever it wants. So they're subject to neither oversight, nor competition. So the average American should care because it's a pocketbook issue. It's also an innovation issue. Who's going to get to decide what new things come into our houses?

DAVID CARR:

People have a close, intimate relationship with the Web in a way they don't other technologies. It's where they see their loved ones. It's where they communicate with people. And they have the precious propriety feelings about it. And I'm not sure if the FCC really knows what they're getting into.

BILL MOYERS:

You've been in touch with Tom Wheeler. Can you tell me what you think is driving him at the moment?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

He doesn't want to spark a war with the industry. He believes that he won't be able to get anything else done if he leans towards calling these guys a utility. What I think he's missing is that he's sparked a war with an entire American populous. We love Internet access. We want it. It is very personal. And to give up on any constraint of these monopolists seems very odd to people. So they're waking up. They're noticing this issue.

DAVID CARR:

I mean, people don't get excited about this until their movie starts stuttering or they can't upload big files. Then they get plenty, plenty excited. People expect it to be like electricity. You expect to turn on the cold water and to have it flow. You expect to plug something in and for it to light up. And you expect to turn on your Internet, and for it to work.

BILL MOYERS:

So if customers are willing, as you are, to pay for a premium service as they do with, as we do with our mobile phone contracts or business class travel, then why not for the Internet?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

This is much more like electricity. It should be available to all at a reasonable price because that's the substrate, that's the input into absolutely every element of American life. Social, economic, cultural. This is just the highway for every kind of transaction we want to engage in.

BILL MOYERS:

Then if it's like electricity, why not treat it as a public utility, a common carriage, as we have telephones and electrical power for so long?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

Well, that's why my first question to Tom Wheeler would be, "Why are you giving up? We seem to have no oversight of this market at all. And yet, because of your short term political expediency needs, you're saying you're not even going to try to have firm legal ground on which to constrain the appetites of these companies to control information."

BILL MOYERS:

Short term political expediency?

BILL MOYERS:

What do you mean?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

The head of the Cable Association, Michael Powell, used to be the chairman of the FCC. He said it would be World War III if the FCC even leaned towards calling these guys a utility. That's what Mr. Wheeler is facing. And the risk is that then those actors march on Capitol Hill, gut his budget, and don't allow him to do the other things he wants to accomplish with the commission. What he's, I think, failing to understand is that this is it. This is the legacy moment for Tom Wheeler. This is when he decides that he actually, he's a regulator and he's going to take a firm hand when it comes to these enormously powerful companies.

BILL MOYERS:

But is he a free agent? I mean, he was in the industry for several years before he came to the FCC. Michael Powell was at the FCC before he took the job that Tom Wheeler once had. I mean, can they be honest brokers?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

Well, he was a cable lobbyist. But he can now rise to the mantle of public leadership and say, this is the important moment. This is it.

DAVID CARR:

The thing is you can't suggest that what he's doing is unreasonable. But I worry that it's going to end up-- we're going to end up with these nodes of innovation. And that we're going to ghettoize, what was supposed to be a national resource. This was-- this whole infrastructure was built by the government. But if you allow all the head ends of it, all the sort of sweet spots of it to lie in private hands, then that whole sort of village common breaks down. And isn't, doesn't reflect a democracy. I mean, it was President Obama that talked about the democratic impulses of the Web and how that needed to be preserved. I haven't seen a lot of that in what he’s done.

BILL MOYERS:

And Tom Wheeler says that, look, the FCC's tried twice to rewrite the rules of Net neutrality. And the appeals court, federal appeals court, has turned thumbs down twice. He's saying, I'm only doing what I can do to write rules that are consistent with what the court has said.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

What's not right about that is that he can do something. The FCC has tried to simultaneously deregulate by not labeling these guys as utilities. And yet, adopt Net neutrality rules. All he has to do is relabel these services as utility services. And then he stands on firm legal footing.

He can forebear from any details of those rules. He doesn't want to apply. The courts have struck this down because it's incoherent. That's the problem. If he marches forward on a clear legal path, he'll be fine. But he wants to avoid World War III on the cable institutions.

BILL MOYERS:

We frame this altogether in commercial terms. But isn’t there a threat to the non-commercial sector, to the scientific sites? To the historical sites, to the cultural sites? To the sites that deal in civic engagement? They are acting from a different motive than the profit motive. Aren’t they at risk here?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

All those sites are like the people in Fort Lee, New Jersey, trying to get across the George Washington Bridge. There are traffic cones being set up on that bridge by a private actor who’s under no constraint. You know, what they’re going to do, where they’re going to squeeze traffic, where they’re going to extract rents. But this is about the free flow of information, and we should all be able to assume the presence of a non-discriminatory, extraordinarily reliable network.

DAVID CARR:

I have to jump in on that. I think to analogize it to what Chris Christie’s aids did on the bridge is assigning motive and punishment in a way that’s really not at work. These guys think they’re up to really good things. They’re not setting out to punish anyone. They just think that the public interests and their interests are perfectly aligned. I don’t agree.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

I don't care about their intentions. We've got a problem when one gatekeeper can have so much control over everything flowing into American houses.

BILL MOYERS:

Take what some of these providers say. They argue that without the power to provide the use of preferential services to the leading content providers, they won’t get the revenue to invent in the future to indebt in the future, you say is still yet out there-- that we have not yet foreseen.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

Over the last several years, Comcast has invested just 15 percent of its revenues in expanding its network. It’s in harvesting mode. It’s making 95 percent plus profits for its broadband product. It has no incentive to expand its network. So yes, they’ll make that argument. But the facts are directly to the contrary.

DAVID CARR:

You know, the cable industry has worked hard to see that homegrown civic initiatives toward broadband have been more or less outlawed in l9 states. I’d really like to see, in this process, some pushback on that. If you’re going to make way for Comcast to own this big a footprint, at least give Americans, American cities, American institutions the opportunity to grow an alternative. And we should see a roll back in terms of preventing cities from building up their own fiber network.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

This industry, AT&T, Verizon, Comcast and Time Warner made $l.5 trillion over the last five years. They have no interest in seeing competition emerge in these cities. And David is right. In l9 states it’s either difficult or impossible for cities to do this for themselves. And mayors know that they need these networks in order to attract businesses, keep social life coherent in their cities, and build up their fabric of their civic life. And so there’s a lot of interest across the country in using assets that cities have.

DAVID CARR:

I used to be a Comcast customer. Now I’m a Verizon FiOS customer. I have fiber optic at my house. I live in New Jersey. It costs money. But it’s highly functional. It works when I want it to. It does what I want it to do. Why aren’t they everywhere? I know it’s a capital intensive business, because you have to put stuff underground, over ground, that last mile to the home, very expensive. But as Susan pointed out, there’s a lot of gold in that. Trillions of dollars. So if you sink the money into investment, you can pull a lot of money out of that business. So why hasn’t that happened?

BILL MOYERS:

You keep returning to the subject of the merger between Comcast and Time Warner. What’s the relationship of that merger to Net neutrality?

DAVID CARR:

Well, it’s sort of where the Internet lives. When we talk about the Web we’re not talking about something that the government built back in the '60s so big institutions could talk to each other. We’re talking about a hybrid system of private and public right of ways and infrastructure that has grown up over time in an ad-hoc way that Commissioner Wheeler and others who are struggling to define and regulate. It’s a very complicated sort of hybrid organism.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

I think we can make it a little simpler. So you’ve got one wire coming from one company coming into everybody’s house. There’s a box at the end of that wire. We call it today a set-top box. But it’s also going to become a Web browser. There is a software platform on that box. Comcast controls that browser. That browser that you’re using to access everything can pick stream picks, Comcast service over Netflix, can pick Comcast telemedicine service over whatever you might want to sign up for. Can pick Comcast educational software over what you might want to have. That’s a very different picture from the permission-free Internet that we’ve all grown up with.

DAVID CARR:

If you think of all the big business wins right now, whether its Airbnb or Uber, what they’re doing is they’re taking available assets that are already out there, and they’re helping you navigate them. There’s a lot of money in that. And as Susan points out, if you control navigation, if you are able to point people in certain ways and send them down paths where you can monetize them, it probably follows that you’re going to sort of favor what you do. They’re in the content business. They own NBC. They own Universal Studios.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

Comcast has an incentive to put up one gateway into its network and then charge for getting in. It did that with Netflix very recently. And if it can do that with the biggest, most popular over-the-top company, it can do it with anybody.

DAVID CARR:

To me to say to people, I’m in favor of Net neutrality, but if you got enough dough, you can bolt it in a special way, I would say that sounds like two Internets, a good Internet and a bad Internet. And I don’t like the idea that somebody can control traffic. To control traffic is to control information and also to control a kind of message.

BILL MOYERS:

Message? The content?

DAVID CARR:

Yes. If my message comes to you slowly and her message comes to you quickly, she’s going to win.

BILL MOYERS:

Did I hear you mutter a moment ago that this potential merger between Comcast and Time Warner is frightening.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

What’s interesting, the consigliore of Comcast, whose name is David Cohen, he’s been described this way in newspapers, has said, now this may sound scary. He says that because the American public is worried about this. It really sounds like Shamu and Godzilla merging. They’re enormous companies. And they just cover everything with bundles of services. And Americans have no choice. The United States stands alone in its dedication to private companies running all of its utility services, with some public oversight. That's always been our history. Other countries started with public companies and have this idea of a public trust for communications. That it, because of all the social spillovers, it needs to be made available to everyone at a reasonable price. We have now got the worst of this bargain. We both have private companies. We're dedicated to that. And no oversight of them. And that's leading to an extraordinarily weak situation. So the answer is not to give up on public oversight, but to make it better. To unleash the regulatory ideal, which is for pro-innovation, pro-American people. We've just fallen down on the job.

DAVID CARR:

I don't think it's as simple as Susan makes it. I watch the Supreme Court grappling with Aereo. What is an Aereo? And here are people who grew up watching “Mash” get pulled in over rabbit ears, trying to deal with an antenna farm that remotely records, programming in the cloud that consumers then can access and pull down. And you could just see them struggling and grappling. I don't think Congress is all that much different. I think we have a cohort of mostly older Americans that is struggling to put get its arms around the future. And they're doing so in sort of confused and inconsistent ways. And I do think companies like Comcast or Google or whoever, that have a firmer grasp on what the, what the future looks like, they're playing a game over the game that Washington doesn't necessarily understand.

BILL MOYERS:

What can we learn from past regulatory battles like this?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

Well, we went through this with electricity and with oil and with railroads. These are infrastructure services that, given half a chance, a private company will try to corner. We need to have government intervention. We're always in this tug of war between rules and an outright, unconstrained private market. Where you have something that is essential for every part of American society, government intervenes to try to make sure that it's available at a reasonable price. We haven't done that.

DAVID CARR:

I do think that the rail analogy is useful because, unlike countries all over the world, we've allowed our rail network to kind of-- we've expected it to thrive on its own. And so, I get on the Acela and I think to myself, I'm riding a bullet train that doesn't go fast. Why is that? And it's because it's going through tunnels that were built during the Civil War.

And in the same way, broadband, true connectivity, true high speed Internet, there are so many countries that are better at this than we are. How is it that we invented the Internet, we have built companies that have pulled billions and billions of dollars out of it. But somehow, we're losing custody of its better properties to other countries. That just seems wrong.

BILL MOYERS:

The FCC is voting on May 15th to move forward with the proposal or not. That's less than two weeks away. What do you think people can do to be heard at that May 15th meeting?

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

The uproar in the country is already causing the FCC to walk back from Wheeler's initial statement that he was never going to move towards treating these guys like a utility. That's already happening. Keeping that pressure up is only going to help because then they have to keep all these options on the table and act like a regulator. So writing into the FCC, writing to your congressman, keeping in touch with your senator. That really is making a difference. The White House is responding.

DAVID CARR:

I do think that consumers have to think back to SOPA and—

BILL MOYERS:

SOPA.

DAVID CARR:

Stop Online Piracy. That the entertainment industry wanted to make fundamental changes in the way the Web is regulated. And they thought it was no big deal. People went ballistic. And, with the support of Google, with the support of Facebook, came off the sidelines and said, you know what? You're going to break the Internet. We don't want you to break the Internet.

That’s ours. Keep your hands off our Internet. If you look at the hierarchy of communication that comes to you over the web, there's your email. What could be more interesting than that? Somebody's thinking about you, sending a message.

You hit the button, and up pops your grandchild. Or, if you want, you move over and you can talk to them in real-time on FaceTime. We're living in an incredibly magical age that all this technology has enabled. And if Google and others start to tell American consumers, look these guys are breaking the Internet and sort of unleashes the flying monkeys, as they did during the debate over SOPA, I think it could tilt the rank.

BILL MOYERS:

David Carr, Susan Crawford, thank you very much for being with me.

DAVID CARR:

Pleasure being with you, Bill.

SUSAN CRAWFORD:

Nice to be here.

BILL MOYERS:

Barack Obama told us there would be no compromise on Net neutrality. We heard him say it back in 2007, when he first was running for president.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA:

To seize this moment we have to ensure free and full exchange of information and that starts with an open Internet. I will take a backseat to no one in my commitment to network neutrality, because once providers start to privilege some applications or websites over others, then the smaller voices get squeezed out and we all lose. The Internet is perhaps the most open network in history and we have to keep it that way.

BILL MOYERS:

He said it so many times that defenders of Net neutrality believed him. They believed he would keep his word, would see to it that when private interests set upon the Internet like sharks to blood in the water, its fate would be in the hands of honest brokers who would listen politely to the pleas of the greedy, and then show them the door.

Unfortunately, it turned out to be the infamous revolving door. Last May, President Obama named Tom Wheeler to be FCC chairman. Mr. Wheeler had been one of Obama’s top bundlers of campaign cash, both in 2008 and again in 2012, when he raised at least half a million dollars for the President’s re-election. Like his proposed rules for the web, that put him at the front of the line.

What’s more, Wheeler had been top gun for both the cable and wireless industries. And however we might try to imagine that he could quickly abandon old habits of service to his employers, that’s simply not how Washington works. Business and government are so intertwined there that public officials and corporate retainers are interchangeable parts of what Chief Justice John Roberts might call the gratitude machine. Round and round they go, and where they stop. Actually they never stop. They just flash their EZ pass as they keep shuttling through that revolving door.

Consider, Daniel Alvarez was a long-time member of a law firm that has advised Comcast. He once wrote to the FCC on behalf of Comcast arguing against Net neutrality rules. He’s been hired by Tom Wheeler.

Philip Verveer also worked for Comcast and the wireless and cable trade associations. He’s now Tom Wheeler’s senior counselor. Attorney Brendan Carr worked for Verizon and the telecom industry’s trade association, which lobbied against Net neutrality. Now Brendan Carr is an adviser to FCC commissioner Ajit Pai, who used to be a top lawyer for Verizon.

To be fair, Tom Wheeler has brought media reformers into the FCC, too, and has been telling us that we don’t understand. We’re the victims of misinformation about these proposed new rules. That he is still for Net neutrality. Possibly, but the public’s no chump and as you can see from just those few examples I’ve recounted for you from the reporting of intrepid journalist Lee Fang, these new rules are not the product of immaculate conception.

So this public comment period is crucial. You have a chance to tell both Obama and Wheeler what you think, so that the will of the people and not the power of money and predatory interests, is heard.

At our website, BillMoyers.com, we'll show you how to get in touch with the FCC and we’ll connect you to the public interest organizations and media reform groups that can help you get your voices heard.

That’s at BillMoyers.com. I’ll see you there and I’ll see you here, next time.

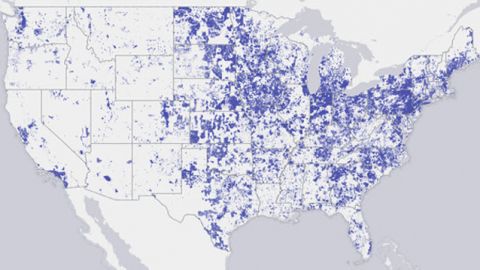

How Connected is Your Community?

How Connected is Your Community?