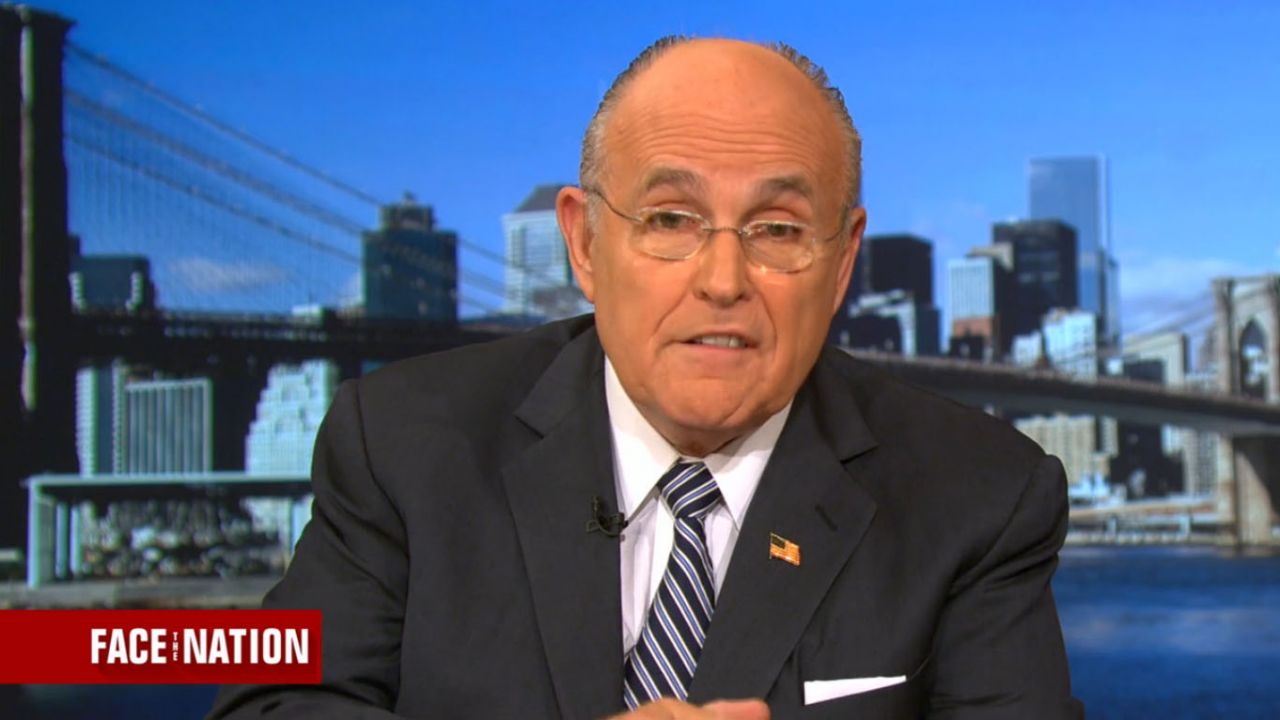

On July 10, 2016 former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani appeared on "Face the Nation" and said: "When you say black lives matter, that's inherently racist."

This post originally appeared at Jewish Journal.

If you weren’t whiplashed, heartsick, nauseated, outraged and exhausted last week, you weren’t paying attention.

Within the span of 24 hours, we were pummeled by horrifying images and unbearable grief — nothing as awful as personally enduring it, but real and real-time enough to scar our spirits, and to put “reality” TV in its infantilizing, counterfeit place.

The killings in Louisiana, Minnesota and Texas were a shared national tragedy. But so far that common trauma has failed to cauterize the wound that created it and that it created. These miserable days since then have united us in our experience of anger, but we remain divided by our experience of race. We cannot agree who the victims and villains are. We demand solutions, but we are polarized by our accounts of the problems. We want justice and we want law and order, but we are split by our explanations for their absence.

When he arrived in Warsaw for the NATO summit, after two black men had been killed by cops in Baton Rouge and Falcon Heights but before five cops had been killed by a black sniper in Dallas, President Obama went to a podium to draw a connection between the shootings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and the severity disproportionately meted out to Americans of color by our criminal justice system.

Those disparities, he said, should trouble all fair-minded people. They make it “incumbent on all of us to say, ‘We can do better than this; we are better than this’ — and to not have it degenerate into the usual political scrum.”

Are we, truly, better than this?

We can’t even agree on what “this” is.

To some Americans, “this” is a black parent having to teach a black son how to “yes, sir” his way out of turning a broken taillight stop into an execution.

To other Americans, like Rudy Giuliani, “this” is a prompt to say that “the reason there’s a target on police officers’ backs is because of groups like Black Lives Matter.”

To some, “this” is a list that did not start with Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Walter Scott, Sandra Bland, Laquon McDonald and Freddie Gray — and that now includes, but does not conclude with, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile.

To others, like talk radio host and former Illinois Rep. Joe Walsh, “this” is a cue to tweet, “This is now war. Watch out Obama. Watch out black lives matter punks. Real America is coming after you.”

To cable news, “this” is a ratings bonanza, an opportunity for infotainment. Even if you didn’t see it, you know how it goes. Former New York Police Department detective Harry Houck shouts that race isn’t a factor in taillight stops; defense attorney Paul Martin shouts back, “You’re not living on the same planet we are.” Political commentator Van Jones says “the statistics don’t lie” about the criminal justice system’s bias against blacks; Houck counters that minorities commit a majority of crimes and “the statistics bear that out, and you don’t want to face that…. Many police officers put their lives on the line for minorities every day, and to say that police departments are systematically racist is a ridiculous statement.” Jones tries to calm the waters: “There’s something called unconscious bias.” Houck retorts, “That’s a new narrative, I know — you guys made that up just recently in the last six months.” On TV, apparently, we are not better than this.

On July 7, as the wrenching video live-streamed by Diamond Reynolds went viral on Facebook, as we watched her 4-year-old daughter Dae’Anna witness her mother’s boyfriend die, as we saw the gun and heard the voice of the cop who killed Castile, as their literal terror became our virtual terror, a second drama shared the nation’s screens.

On Capitol Hill, FBI director James Comey was grilled by the House Oversight Committee about not recommending criminal charges against Hillary Clinton. Democrats, though relieved by his decision, fumed about the fodder his press conference and testimony gave Clinton’s opponents to claim she is unfit for office. Republicans, fuming about his decision, wanted Comey to say, as Donald Trump tweeted, that the system is rigged — that once Bill Clinton met with Attorney General Loretta Lynch on her plane, the fix was in. But to the allegation of a conspiracy, Comey responded, “Look me in the eye and listen,” and gave no ground.

Watching the hearing on TV while, at the same time, watching the Sterling and Castile videos on social media, I was struck by how Comey bridged the two stories. It was Comey who had irritated Democrats and others last October by suggesting that rising crime rates might be attributable to cops’ reluctance to get out of their cars for fear that they would be unfairly depicted in viral videos. “A chill wind,” he said, has been “blowing through American law enforcement” over the past year, deterring cops from effective policing. He said it twice within a few days, leading White House press secretary Josh Earnest to counter, “The evidence that we’ve seen so far doesn’t support the contention.” Undeterred, Comey said it again in May, again arousing pushback.

I wonder how much of that resistance is substantive, and how much is tribal. When Trump says he is not shackled by political correctness, what he means is that if you hold him accountable for his racism, he will try to bully you for upholding America’s highest ideals. But there are times when the ways we pursue our ideals can surface uncomfortable tensions between them. This is especially true, and especially troubling, in the case of race and justice, and it is not racist to say so. But the fear of that accusation can make it hard to talk about them honestly. Even if the partisan climate were less toxic, even if the business model of the media were not to inflame and monetize civic conflict, solving our race and justice problem will take more than the political leadership to put the right policies in place. Finding common ground on moral issues requires moral leadership.

Last February, Comey gave a speech at Georgetown University in which he quoted the song “Everyone’s a Little Bit Racist” from the Broadway show, “Avenue Q”:

Look around and you will find

No one’s really color blind.

Maybe it’s a fact

We should all face

Everyone makes judgments

Based on race.

What Comey says in that speech about race and justice is uncommon for its candor and its empathy. Here’s a sample:

Those of us in law enforcement must redouble our efforts to resist bias and prejudice. We must better understand the people we serve and protect — by trying to know, deep in our gut, what it feels like to be a law-abiding young black man walking on the street and encountering law enforcement. We must understand how that young man may see us. We must resist the lazy shortcuts of cynicism and approach him with respect and decency.

In that speech, and in another he gave last year at the University of Chicago Law School, the one in which he first mentioned the “chill wind,” Comey wrestles with some of America’s most intractable problems. I don’t know if he’s right about the way ubiquitous videos may undermine policing, and neither does he; he’s careful to offer it as a conjecture, though one informed by widespread anecdotes in the law enforcement community. But I would rather have his speculation and his moral leadership than the demagoguery of the Rudy Giulianis and of the Trumps whom they support.

I will miss Obama’s moral leadership. If Clinton succeeds him, I hope her passion for policy, beneficial as that is, isn’t the last step she takes toward the pulpit the presidency provides.

Imagine if Clinton and Comey, together, were to lead the nation to common ground on race and justice. That’s just a dream, I know. But what could be the best answer to, “Are we better than this?” is this:

“I have a dream.”