This post first appeared at The Nation.

(Photo: Michael Fleshman/flickr CC 2.0/edited from original)

Freddie Gray’s neighborhood in Baltimore had the highest incarceration rate of anywhere in the city. More than 450 adults from Sandtown-Winchester are in state prison, and one in four juveniles were arrested from 2005 to 2009. These statistics are indicative of a broader crisis in the city — a third of Maryland’s prison population is from Baltimore.

The problem of mass incarceration has been all over the news recently. One overlooked aspect of the story is how the legacy of mass incarceration denies equal citizenship long after the offenders have paid their debts to society. Nationally, one in 13 African Americans — 2.2 million people — are prohibited from casting a ballot because of felon disenfranchisement laws.

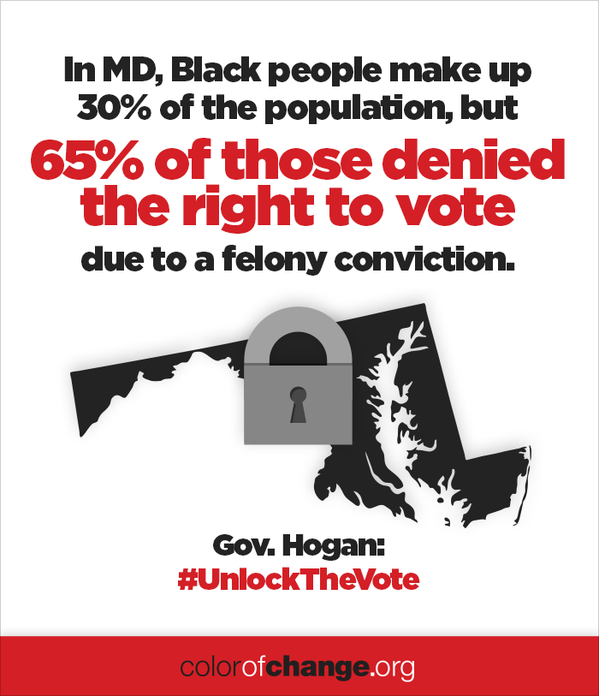

Earlier this month the Maryland legislature passed a bill automatically restoring voting rights for ex-felons, allowing them to vote while on parole or probation. The legislation would restore voting rights to nearly 40,000 people and be particularly beneficial to African Americans, who make up 30 percent of the state’s population but account for 65 percent of those denied voting rights. The bill awaits the signature of Maryland Republican Governor Larry Hogan, who has said “I believe in second chances.”

The Baltimore Sun explained the legislation and editorialized in its favor:

At present, people who have lost their right to vote as a result of a criminal conviction don’t automatically get it back when they return to their communities. In Maryland, ex-offenders can’t register to vote until they have fulfilled all the terms of their sentences, including any period of probation or parole after their release. That can add years to the time they must wait before their voting rights are fully restored.

The measure would instruct the state Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services to notify ex-offenders upon their release from prison that their voting rights will be restored and to give them a voter registration form along with another document offering them an opportunity to register and help filling out the form. It would also require the department to provide similar notifications to people discharged from prison before the bill’s effective date of Oct. 1, 2015 and allow prisoners who are still incarcerated to participate in educational programs informing them of their rights under the law before their release.

Fifteen to 20 states have adopted similar measures, as part of a nationwide rethink of our country’s broken criminal justice system. As the Sun notes, the legislation wouldn’t solve the myriad problems in Baltimore, but it would be a good first step.

“The ability to vote is a key factor in helping people reintegrate back into their communities after returning from prison,” Ben Jealous and Janet Vestal Kelly wrote recently. “The right to vote offers a sense of ownership to our democracy — a reminder that each of us holds the key to our own futures through the democratic process.”