This post first appeared at The American Prospect.

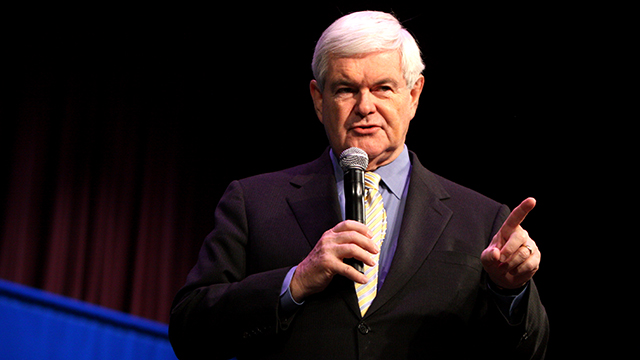

Newt Gingrich’s “Contract With America” is key to understanding the 114th Congress. (Photo: Gage Skidmore/flickr CC 2.0)

As the 114th Congress begins, Republicans are signaling their desire to prove their party can not only win elections, but can govern. “GOP goal: Prove it can lead,” was the title of a page A1 story in Sunday’s print edition of the Washington Post. “GOP agenda for Congress: Challenge Obama, prove they can govern,” CNN blared the next day.

That governing agenda surely includes speeding up energy production, slowing down Obamacare’s implementation and continued foot-dragging on immigration reform. But top party leaders readily confess their deeper motives. “We have to show that we can be a productive party, and that, I think, will have a direct effect on whether we’re able to elect a Republican as president in 2016,” said Senator John McCain, the party’s 2008 presidential nominee. New Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell was even more blunt: “I don’t want the American people to think that, if they add a Republican president to a Republican Congress, that’s going to be a scary outcome.”

So there you have it. The primary objective for congressional Republicans over the next two years is to live by the partisan-electoral version of the Hippocratic oath: Do no harm to the party’s chances to establish unified control of Washington in January 2017.

If the past six decades are any guide, however, this is an ambitious goal. Indeed, by the end of the Obama presidency, the federal government will have been divided for nearly 70 percent of the previous 64 years. But as I argue in my new book, The Stronghold: How Republicans Captured Congress but Surrendered the White House, Republicans, and conservatives in particular, should be rather pleased with their congressional domination in the quarter century since the end of the Reagan-Bush (41) era — even if the GOP’s congressional successes were attended by, and in many ways the cause of, the struggles of its presidential nominees. In this protracted era of divided government, controlling Congress makes a lot more sense for Republicans than occupying the Oval Office.

To understand why, let’s return to the moment of conception for today’s Republican majorities on Capitol Hill, and the seminal Republican figure of the past half-century: the 1994 “Republican Revolution” and Newt Gingrich. Despite conservatives’ unabated veneration of Ronald Reagan, the truth is that the Gipper left a far less indelible imprint on recent American politics than the Georgia speaker. Yet, the onset of the 114th Congress has occasioned surprisingly few mentions of the arrival, 20 years ago this week, of the historic 94th Congress that put the GOP in control of both chambers of Congress for the first time in 40 years.

The Republicans’ path to power was paved by the “Contract with America.” In retrospect, the “Contract” was notable for two reasons.

First, as my political science colleague Ron Rapoport has shown, it was designed to appeal especially to the reformist impulses of the nearly one in five Americans who voted for Ross Perot in the 1992 presidential election. As I remind readers in my book, the Contract’s second notable feature, very much related to the first, was its avoidance of specific policy proposals in favor of institutional reforms proposed as an indirect means to delivering good policy. Slightly condensed here for brevity’s sake, the document’s eight key tenets were:

- Require all laws that apply to the rest of the country also apply to the Congress;

- Hire an independent firm to audit Congress for waste, fraud, or abuse;

- Cut the number of House committees, and reduce committee staff by one-third;

- Limit the terms of committee chairs;

- Ban proxy voting in committees;

- Open all committee meetings to the public;

- Require a three-fifths majority vote to pass a tax increase; and

- Implement zero-base-line budgeting for the federal budget.

Although the audit, tax increase supermajority and zero-base-budgeting provisions offer a vague promise of fiscal restraint, the Contract was not a policy agenda so much as it was a broad political indictment of how Congress does business packaged as a laundry list of proposed reforms. Given their four-decade hegemony to that point, perhaps Democrats deserved the indictment and the public’s ire toward Congress.

Ten federal elections and 20 years of mostly Republican rule in Congress later, however, the GOP can no longer shift blame across the partisan aisle for a Congress that, just last year, saw its public approval sink into single digits. But then again, Republicans never really promised to deploy congressional power to fundamentally change national policy. The elevation of procedural and political reform over substantive policy agendas can be traced right back to the Republicans’ original Contract.

That said, Democrats, liberals and other cynics tempted to scoff at congressional Republicans’ pledges to use their 114th Congress majorities to solve national problems and govern soberly should remember that the two parties approach the business of governing very differently. To Republicans, modern governing means to slash, slow, cut or otherwise impede federal functions, programs and growth. Here, Hippocrates is turned on his head: The GOP’s principal policy objective is to do ample harm.

Debt-ceiling shenanigans; Ted Cruz-led government shutdowns; more than four dozen futile Republican House caucus votes to repeal or otherwise gut Obamacare — these actions reveal the GOP’s governing mindset and helped make the 113th Congress the most unproductive in history. Because a “productive” Congress means something entirely different to Republicans than it does to Democrats, Speaker John Boehner should be taken at his word when he said on national television that Congress “should not be judged on how many new laws we create [but] on how many laws we repeal.” Or as anti-tax guru Grover Norquist told me in an interview for The Stronghold, “you can govern with just the House.” Delivered without a hint of irony, Norquist’s maxim at first seemed absurd to me — until I considered the fundamental asymmetries between the two major parties’ governing philosophies, especially at the national level. Adding Republican control of the Senate to their House majority only solidifies the GOP’s ability to govern by obstruction.

As the Prospect’s own Paul Waldman has observed, Mitch McConnell’s goal as the new Senate majority leader is “pretty clever;” it’s to make his caucus look “a little more sober and responsible — not so much that they actually do a lot of legislating and make substantive compromises with Obama” but to protect the party’s 2016 nominee. It’s actually more than that: It’s very smart politics, both ideologically and practically. Having rarely suffered electoral blowback from this strategy over the past 20 years, why would — and given their view about federal power, why should — Republicans change now?

So don’t be surprised a year from now when, as the presidential primary season begins and the television trucks and field operatives collectively descend upon Des Moines, Capitol Hill reporters are reflecting back on a year marked by few legislative achievements from the 114th Congress. Some bills will surely pass both chambers and die on President Obama’s desk, if only to make claims that Obama is the leader of the real “party of no.” But the GOP may not produce much because it doesn’t intend to — and for the past two decades never really has.