This post first appeared at TalkPoverty.

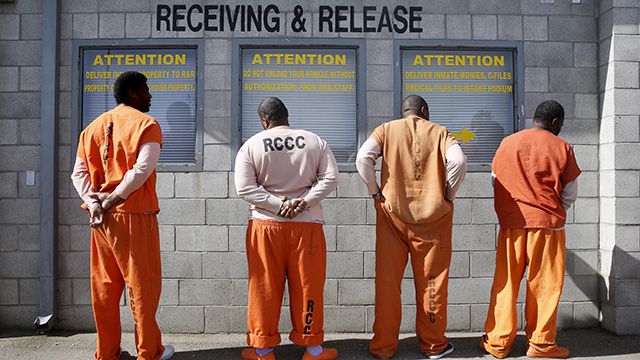

Prisoners from Sacramento County await processing after arriving at the Deuel Vocational Institution in Tracy, California on Feb. 20, 2014. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli)

Criminal justice systems across the country have come to accept, and perpetuate, a shameful standard of justice for poor people. The basic humanity of the indigent accused is too often denied, and the democratic necessity of access to effective counsel is too often ignored.

Gideon’s Promise is a movement of hundreds of public defenders nationwide who are working together to change this unacceptable status quo.

In 1963, when Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, civil rights abuses were prevalent and devastating in the arena of criminal justice. So it is no coincidence that during that same year, the United States Supreme Court sought to address the role that race and class played in the administration of criminal justice.

In Gideon v. Wainwright, the Supreme Court required that the state provide poor people accused of a crime with an attorney. It noted that a layperson simply cannot effectively navigate the labyrinth of laws and procedures that make up the criminal justice system. Only the right to counsel would ensure that a person accused of a crime would receive justice.

But the right to counsel is only meaningful if state-appointed attorneys have the same skill, training, resources and level of commitment as lawyers who represent people with means. As I began working on criminal justice reform efforts across the South a decade ago, I saw systems that fell far short of providing basic standards of representation for poor people. I met countless young public defenders who had begun their careers filled with enthusiasm, only to have the passion beaten out of them by a system that effectively expects public defenders to help process poor people into prison cells.

These lawyers were deprived of the resources, training and support they needed to live up to their constitutional obligation. They were forced to handle crushing caseloads that didn’t allow them to give the time their clients deserved and needed. Many began to feel hopeless and eventually quit. Others were worn down, resigned to the status quo. A few remained inspired, continuing the Sisyphean task of fighting a system that had abandoned its quest for equal justice. But all too often these individuals were like a lone voice screaming against a deafening wind.

In 2007, my wife and I founded Gideon’s Promise to build a strong community of public defenders who would have the training and support necessary to immediately improve the standard of representation for their clients. We wanted to develop this community into a movement — one focused on changing a criminal justice culture that is anything but just, and pushing back against the forces that pressure public defenders to simply process clients.

Gideon’s Promise began with just 16 young public defenders drawn from two offices. To date, more than 300 public defenders in 15 states have participated in our initial, three-year training and support program. A national faculty comprised of more than 60 experienced public defenders volunteer as our trainers and mentors. We have added programs that serve our graduates, senior lawyers and public defender leaders. With more than 35 “partner” public defender offices, Gideon’s Promise is changing the landscape of public defense for tens of thousands of people who depend on court-appointed counsel each year. Through partnerships with law schools, we are also creating a pipeline for recent graduates to join our effort where the need is greatest. Finally, by working with jurisdictions across the nation to share our model, Gideon’s Promise has indeed evolved into a comprehensive movement of inspired public defenders committed to transforming criminal justice in America.

There is no greater threat to equal justice than when our public defenders are beaten into submission. At that point, a poor person accused of a crime has no chance. But through a strong and supportive community like Gideon’s Promise, lawyers for the poor can stay inspired and continue to fight one of the least popular, but most important, civil and human rights battles of our day.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.