This post first appeared at Mother Jones.

On Election Day, political campaigns, candidates, consultants, and pollsters pay close attention to who votes and why — and so does Facebook. For the past six years, on every national Election Day, the social-networking behemoth has pushed out a tool — a high-profile button that proclaims “I’m Voting” or “I’m a Voter” — designed to encourage Facebook users to vote. Now, Facebook says it has finished fine-tuning the tool, and if all goes according to plan, on Tuesday many of its more than 150 million American users will feel a gentle but effective nudge to vote, courtesy of Mark Zuckerberg & Co. If past research is any guide, up to a few million more people will head to the polls partly because their Facebook friends encouraged them.

Yet the process by which Facebook has developed this tool — what the firm calls the “voter megaphone” — has not been very transparent, raising questions about its use and Facebook’s ability to influence elections. Moreover, while Facebook has been developing and promoting this tool, it has also been quietly conducting experiments on how the company’s actions can affect the voting behavior of its users.

Facebook officials insist there’s nothing untoward going on. But for several years, the company has been reluctant to answer questions about its voter promotion efforts and these research experiments. It was only as I was putting the finishing touches on this article that Facebook started to provide some useful new details on its election work and research.

So what has Facebook been doing to boost voter participation, and why should anyone worry about it?

Since 2008, researchers at the company have experimented with providing users an easy way to share with their friends the fact that they were voting, and Facebook scientists have studied how making that information social — by placing it in their peers’ feeds — could boost turnout. In 2010, Facebook put different forms of an “I’m Voting” button on the pages of about 60 million of its American users. Company researchers were testing the versions to understand the effect of each and to determine how to optimize the tool’s impact. Two groups of 600,000 users were left out to serve as a control group — one which saw the “I’m Voting” button but didn’t get any information about their friends’ behavior, and one which saw nothing related to voting at all. Two years later, a team of academics and Facebook data scientists published their findings in Nature magazine.

In the 2012 election, Facebook proclaimed that it would again be promoting voter participation with the “I’m Voting” button. On Election Day, it posted a note declaring, “Facebook is focused on ensuring that those who are eligible to vote know where they can cast their ballots and, if they wish, share the fact that they voted with their friends.”

But this wasn’t entirely true, because, once again, Facebook was conducting research on its users—and it wasn’t telling them about it. Most but not all adult Facebook users in the United States had some version of the voter megaphone placed on their pages. But for some, this button appeared only late in the afternoon. Some users reported clicking on the button but never saw anything about their friends voting in their own feed. Facebook says more than 9 million people clicked on the button on Election Day 2012. But until now, the company had not disclosed what experiments it was conducting that day.

“Our voter button tests in 2012 were primarily designed to see if different messages on the button itself impacted the likelihood of people interacting with it,” says Michael Buckley, Facebook’s vice president for global business communications. “For example, one treatment said, ‘I’m a Voter.’ Another treatment said, ‘I’m Voting.'”

The company also tested whether the location of the button on the page had any effect in motivating a user to declare that he or she were voting. “Some of [the different versions] were more likely to result in clicks,” Buckley says, “but there was no difference…in terms of the potential ability to get people to the polls. Bottom line, it didn’t matter what the button said.”

According to Buckley, there were three reasons many Facebook users didn’t see the voter megaphone in 2012. The first was a variety of software bugs that caused a large number of people to be excluded from seeing the tool. This might have kept the button off of millions of users’ pages. In addition, some users missed the button because they were part of a control group, and others may not have logged in at the right time of day. Buckley insists that the distribution of the voter megaphone in 2012 was entirely random—meaning Facebook did not push the voting promotion tool to a certain sort of user.

“We’ve always implemented these tests in a neutral manner,” Buckley insists. “And we’ve been learning from our experience and are 100 percent committed to even greater transparency whenever we encourage civic participation in the future.”

Until now, transparency has not been Facebook’s hallmark. For the past two years, my colleagues at TechPresident.com and I have have made a steady stream of requests for details on Facebook’s 2012 voter megaphone research. We were met with silence or vague promises that someday, when the research was published in an academic journal, we’d get some information about what the company was doing. That suddenly changed this week when I started asking Facebook about a different but related experiment it conducted during the 2012 election.

In the fall of 2012, according to two public talks given by Facebook data scientist Lada Adamic, a colleague at the company, Solomon Messing, experimented on the news feeds of 1.9 million random users. According to Adamic, Messing “tweaked” the feeds of those users so that “instead of seeing your regular news feed, if any of your friends had shared a news story, [Messing] would boost that news story so that it was up top [on your page] and you were much more likely to see it.” Normally, most users will see something more personal at the top of the page, like a wedding announcement or baby pictures.

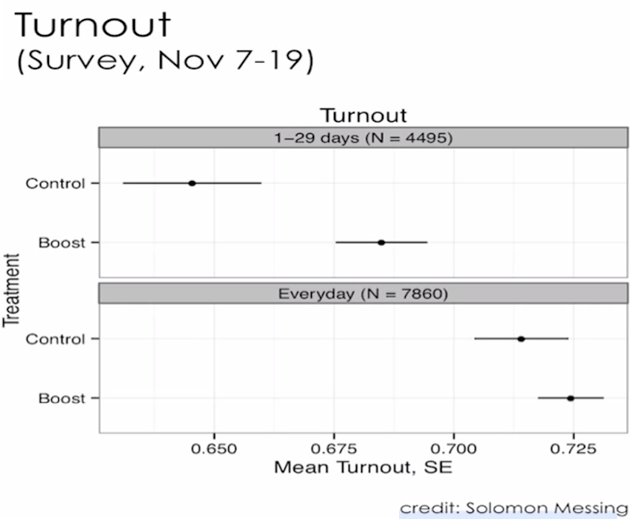

Messing’s “tweak” had an effect, most strongly among occasional Facebook users. After the election, he surveyed that group and found a statistically significant increase in how much attention users said they paid to government. And, as the below chart used by Adamic in a lecture last year suggests, turnout among that group rose from a self-reported 64 percent to more than 67 percent. This means Messing’s unseen intervention boosted voter turnout by 3 percent. That’s a major uptick (though based only on user self-reporting).

Days ago, after I asked Facebook about Messing’s work, the company took down the YouTube video of that Adamic lecture, which had taken place at an annual public conference called News Foo that was attended by hundreds of journalists and techies. (You can view my cached copy of her talk here.) It was as if Facebook didn’t want users to know it had been messing with their news feed this way—though the company says it was only trying to protect these findings so Messing could publish an academic paper based on this experiment.

Buckley, the Facebook spokesman, insists that Messing’s study was an “in product” test designed to see how users would interact with their pages if their news feeds more prominently featured news shared by friends. Drawing from a list of 100 top media outlets—”the New York Times to Fox, Mother Jones to RushLimbaugh.com,” Buckley says—Facebook tested whether showing users stories their friends were sharing from those sites would affect user engagement with the site (meaning commenting, liking, sharing and so on) as well as voter participation. Facebook found there was no decrease in users’ interaction. “This was literally some of the earliest learning we had on news,” Buckley says. “Now, we’ve literally changed News Feed, to reduce spam and increase the quality of content.”

It is curious that Facebook officials apparently thought that testing such a major change in its users’ feeds in the weeks before the 2012 election—precisely when people might be paying more attention to political news and cues—was benign and not worth sharing with its users and the public. Likewise, Facebook failed to disclose and explain for two years why its promise to give all of its American users the ability to share their voting experience had misfired. And, according to Buckley, the public will not receive full answers until some point in 2015, when academic reports fully describing what Facebook did in 2012 are expected to be published.

It’s not surprising that Facebook has been reticent to discuss its product experiments and their impact on voting. After all, most of its users have no idea that the company is constantly manipulating what they see on their feeds. In June, when a team of academics and Facebook data scientists revealed that they had randomly altered the emotional content of the feeds of 700,000 users, the company was met with global outrage and protest. The actual impact of this research into “emotional contagion” was tiny; the data showed that a user would post four more negative words per 10,000 written after one positive post was removed from his or her feed. Still, people were enraged that Facebook would tamper with the news feed in order to affect the emotions of its users. (The lead academic researcher on that study, Jeff Hancock, needed police protection.)

There may be another reason for Facebook’s lack of transparency regarding its voting promotion experiments: politics. Facebook officials likely do not want Republicans on Capitol Hill to realize that their voter megaphone isn’t a neutral get-out-the-vote mechanism. It’s not that Facebook uses this tool to remind only users who identify themselves as Democrats to vote—though the company certainly has the technical means to do so. But the Facebook user base tilts Democratic. According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project, women are 10 points more likely to use this social network than men; young people are almost twice as likely to be on Facebook than those older than 65; and urbanites are slightly more likely to turn to Facebook than folks in rural areas. If the voter megaphone was applied even-handedly across Facebook’s adult American user population in 2012, it probably pushed more Obama supporters than Romney backers toward the voting booth.

This is the age of big data and powerful algorithms that can sort people and manipulate them in many hidden ways. Using those tools, national political campaigns, building on the Obama 2012 reelection effort, are learning how to “engineer the public” without the public’s knowledge, as sociologist Zeynep Tufekci has warned. Consequently, there is a strong case for greater Facebook transparency when it comes to its political efforts and experiments. Clearly, the company is proud of the voter megaphone. After a successful test run in the Indian national elections this spring, the company announced that it would be putting the tool on the pages of users in all the major democracies holding national elections this year and that it would also deploy the tool for the European Union vote. According to Andy Stone, a spokesman for Facebook’s policy team, the megaphone was seen by 24.6 million Brazilians during the first round in that nation’s recent election.

On Tuesday, the company will again deploy its voting tool. But Facebook’s Buckley insists that the firm will not this time be conducting any research experiments with the voter megaphone. That day, he says, almost every Facebook user in the United States over the age of 18 will see the “I Voted” button. And if the friends they typically interact with on Facebook click on it, users will see that too. The message: Facebook wants its users to vote, and the social-networking firm will not be manipulating its voter promotion effort for research purposes. How do we know this? Only because Facebook says so.