This post first appeared at Demos.

The Supreme Court said Saturday that, for the first time, it is allowing a voting law to be used for an election even though a federal judge, after conducting a trial, found the law is racially discriminatory in both its intent and its impact, and is an unconstitutional poll tax. It is not only not a good look for the court, it is an abdication of the federal responsibility to protect every American voter from racially discriminatory voter suppression.

These continuing voter restrictions are the worst attack on Americans’ voting rights since Reconstruction led to the Jim Crow era. We are in the middle of the storm that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg described in her Shelby County dissent. Studies show that recent restrictions on voting were more likely to be introduced and adopted in places that saw increased political participation from lower-income people and people of color.

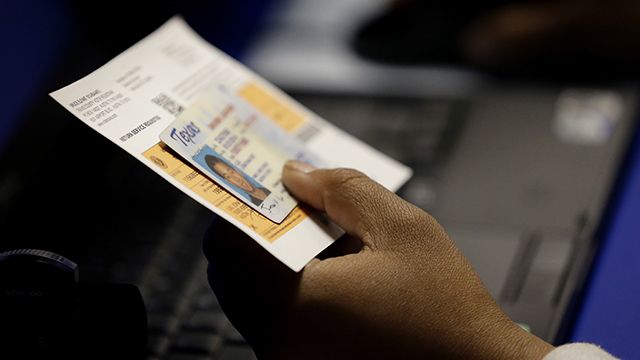

Voting in Texas starts Monday, and the new law only allows seven forms of acceptable identification, including a gun permit or a military ID but not a student ID from a state institution. The federal district court found that African-American registered voters are 305 percent, and Hispanic registered voters 195 percent, less likely to have one of these seven forms of ID. In the words of Attorney General Holder, these voter-ID restrictions are “inconsistent with our ideals as a nation… founded on the principle that all citizens are entitled to equal opportunity, equal representation and equal rights.”

Justice Ginsburg dissented from the Court’s decision to allow Texas’ restrictive voter ID law to go into effect for this election because “the greatest threat to public confidence in elections in this case is the prospect of enforcing a purposefully discriminatory law, one that likely imposes an unconstitutional poll tax and risks denying the right to vote to hundreds of thousands of eligible voters.”

Ginsburg’s dissent explained that the law “may prevent more than 600,000 registered Texas voters (about 4.5 percent of all registered voters) from voting in person for lack of compliant identification. A sharply disproportionate percentage of those voters are African-American or Hispanic.” At trial, experts testified that as many as 1.2 million Texas voters didn’t have the required ID, which would mean Texas is about to start their voting even though almost one in 10 voters may be barred from casting a ballot.

It is particularly galling that the court relies on the principle that voting rules shouldn’t be changed close to an election to allow Texas’ new voting restrictions when the law wouldn’t even be in place had it not been for the Supreme Court’s decision to remove the federal protection that had previously prevented racially discriminatory changes to voting laws from going into effect. That mistaken decision allowed for the creation of the new “status quo” which the court now refuses to disturb.

Before the court’s Shelby County decision in June 2013, the Voting Rights Act required that certain jurisdictions — mostly former slave states, but other places too — with a history and continued instances of discrimination “pre-clear” changes to voting rules that would impact voting rights for people of color. This put the appropriate burden on these states to show their changes wouldn’t have a racially discriminatory impact on voting, instead of putting the burden on people of color to wait until the law was in place and then show the racially discriminatory impact of the new voting restrictions while their voting rights were being burdened.

For nearly 50 years this system worked. The new Texas voter-ID requirements were blocked by the Justice Department from going into effect when they were passed because it was clear that they would have a disproportionately negative impact on voters of color. But Texas moved to implement its new ID requirements the day after the Supreme Court’s Shelby County decision got rid of that system. This is exactly what Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg warned of in her dissent in that case: that getting rid of pre-clearance when it was continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes was like throwing out your umbrella in a rainstorm because you weren’t getting wet.

While the general principle of not changing voting rules close to an election makes sense, Texas’ restrictive identification law has only been used for a few small elections, and never a high turnout federal election, whereas Texas’ previous set of voter identification had been in place since 2003. As Ginsburg argued, poll watchers and voters are likely to be more familiar with the previous standards in place for the prior decade, so allowing the law to be in place now will likely cause more confusion.

As an additional affront, this court’s conservative majority is now notorious for having more solicitude for the concerns of the country’s wealthiest donors — who earlier this year were given the right to spend even more money to impact the political system in McCutcheon v. FEC — than they have for the hundreds of thousands of Americans whose most fundamental right of political participation, the right to vote, is being unconstitutionally burdened. Add that to Citizens United, which unleashed direct corporate spending in federal elections for the first time in a century — and it’s clear that the court is simultaneously making it easier to buy an election and harder to vote in an election.

One reason why elections are so important is because Americans feel differently about important issues (with notable divided views on economic issues between the 10 percent of the richest Americans that make up the donor class and the majority, and between African-Americans and Caucasians on racial issues.) The court has allowed voting rules to be manipulated in ways designed to make the electorate whiter, wealthier and older, at the same time the court’s decisions strengthen the political power of the donor class which is also whiter, wealthier and older than America. This has a tremendously distorting effect on our democratic decision making.

The Supreme Court has failed to protect voting rights not just in Texas, but recently in Ohio and North Carolina as well.

The court denied recent requests from plaintiffs seeking to stop restrictions on voting in Ohio (limiting early voting and doing away with the “golden week” when people could register and vote at the same time) and North Carolina (ending same day registration which allowed people to register and vote at the same time, and making it harder to count provisional ballots). The one ray of light on voting rights at the federal level was the Supreme Court’s decision to stay the 7th Circuit’s decision which would have reversed the lower court and allowed Wisconsin to implement its strict voter-ID law. By Wisconsin’s own admission the law could have disenfranchised up to 10 percent of the state’s voters, since 300,000 registered Wisconsin voters do not have the required ID; they are disproportionately African-American and Latino.

While the US Supreme Court fails to provide adequate federal protections for voting rights, this week the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that their state’s photo ID violated their state constitution, writing that “the legislature cannot, under color of regulating the manner of holding elections, which to some extent that body has a right to do, impose such restrictions as will have the effect to take away the right to vote as secured by the Constitution.” That court examined what it means to be a qualified voter, and found that the only allowable requirements were that an individual be an American citizen, resident of the state, at least 18 years old and registered to vote. The Arkansas Supreme Court held that state shouldn’t also be able to set an additional bar for voting by requiring certain specific kinds of photo identification, writing that “to hold otherwise would disenfranchise Arkansas voters and would negate ‘the object sought to be accomplished’ by the framers of the Arkansas Constitution.”

It took the hard fought victories of the Civil Rights era to stop the abuses of power by those in control who sought to maintain their power by excluding people of color from the country’s political system. Remember, the Supreme Court didn’t strike down the poll tax until 1966 in Harper v Virginia. Fifty-one million eligible Americans still aren’t registered to vote, and are therefore invisible to the political system. This is a disservice to all of us, as it means our government does not truly reflect all of our people. We need to focus on how to facilitate registration and increase participation to strengthen our democracy through common sense improvements such as same-day registration (shown to increase participation by 10 points), and Congress must act to restore the Voting Rights Act.

When the Supreme Court fails to protect our elections from partisan and racially motivated manipulation, the burden may fall disproportionately on some, but we will all pay the cost.