This post originally appeared at ThinkProgress.

In mid-November of 2012, hundreds of tuxedo-clad Republican lawyers gathered at a hotel ballroom in Washington, DC. They were a mix of heads hung in dejection and chests puffed out in compensatory bluster. Less than two weeks earlier, they’d seen President Obama vanquish his opponent at the polls. Their last chance to knock a hated president out of office — and their last real chance to halt that’s president’s even more hated health reforms — ended in failure. They and their allies had made their best case that liberalism was a path to economic ruin, and the American people had lined up at their polling places to pull the lever for liberalism.

And yet, at this annual gathering of the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies, arguably the most powerful legal organization in the country, Justice Samuel Alito was defiant. Not long after rising to give his keynote address to the room full of conservative senators, judges and attorneys gathered before him, Alito launched into a story of a particularly uninspiring law professor whose course he took in law school. The professor, Alito recalled, authored a book in 1970 warning of a decaying society trapped in a “moment of utmost sterility, darkest night, most extreme peril.”

At this point in his speech, Alito paused, and looked over the roomful of lawyers still licking their wounds from Mitt Romney’s very recent defeat. “Our current situation,” he told them, “is nothing new.”

Justice Alito’s speech came during a brief moment of respite between two great constitutional battles. Just a few months earlier, the Court had rejected a request that it repeal the Affordable Care Act in its entirety, based on a tenuous reading of the Tenth Amendment that one prominent conservative judge dismissed as having no basis “in either the text of the Constitution or Supreme Court precedent.” Justice Alito dissented in the Court’s health care decision. He wanted Obamacare gone.

Almost exactly one month after his speech, a gunman named Adam Lanza walked into an elementary school in Sandy Hook, Connecticut, and murdered 26 people, 20 of whom were children. What followed was a nationwide debate over the proper way to solve gun violence and over the scope and the wisdom of the Second Amendment. Many of the lawyers and lawmakers who attended Justice Alito’s speech would fight hard — and, ultimately, successfully — to defeat President Obama’s proposals to prevent future Sandy Hooks.

In the moment of calm between these two storms, Justice Alito let the audience know where he stood on both questions. Referring to the text of the Constitution, Alito quipped that “[i]t’s hard not to notice that Congress’ powers are limited, and you will see there is an amendment that comes right after the First Amendment, and there’s another that comes after the Ninth Amendment.” He spent much of the rest of the speech criticizing legal arguments the Obama administration had made in his Court.

So, when Chief Justice Roberts opened the final session of the Supreme Court’s term on Monday by announcing that Justice Alito would deliver both of the Court’s remaining opinions, liberals immediately knew that they were about to hear some very bad news. In quick succession, Alito dealt sharp blows to public sector unions and to women whose employers object to birth control.

A Straight Face

If Alito’s Hobby Lobby opinion — the second of the two decisions he handed down on Monday — proves anything, it is that Alito has mastered the art of reading legal authorities that cut sharply against his position, and then authoring a legal opinion that passes them off as if they actually bolster his argument. In Hobby Lobby, Alito was confronted by decades of legal precedents establishing that religious liberty claims could not be used to diminish the rights of third parties, especially in the employment context. Worse, at least for Alito’s belief that employers with religious objections to birth control could deny legally mandated coverage to their employees, Hobby Lobby turned upon how the Court interpreted a 1993 law — a law known as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act or RFRA — that explicitly stated that its purpose was to “restore the compelling interest test” set out by these earlier precedents after that test was overruled by an unpopular Supreme Court decision. This was the same legal test that was in place when the Court held that “[w]hen followers of a particular sect enter into commercial activity as a matter of choice, the limits they accept on their own conduct as a matter of conscience and faith are not to be superimposed on the statutory schemes which are binding on others in that activity.”

Yet Alito ignored Congress’s clearly stated purpose, he offered little explanation for why he was justified in doing do, and what little justification he did offer falls apart upon a very cursory inquiry. At one point in his opinion, for example, Alito points to a 2000 amendment to a largely irrelevant provision of RFRA, claiming that the amendment was “an obvious effort to effect a complete separation from First Amendment case law.” Elsewhere, Alito argues that RFRA strengthened the legal protections available to religious objectors prior to 1990. Both claims, however, are difficult to square with RFRA’s statement that its entire purpose is to restore prior precedents — and there is nothing in the 2000 amendment which alters this statement of purpose.

Hobby Lobby is also the latest in a series of decisions Alito has handed down diminishing the rights of women in the workplace. Prior to Hobby Lobby, his most famous decision was undoubtedly Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire, the pay discrimination case that Congress overturned in the very first bill President Obama signed into law.

Alito, however, does not appear at all humbled by the experience of having a successful presidential candidate campaign against his most well-known opinion and then eradicate that opinion just over a week after moving into the White House. Last year, in an opinion with potentially much further reaching consequences than Ledbetter, Alito gutted a core protection helping prevent workers from being racially or sexually harassed by their boss. Harassment suits of this kind are notoriously difficult to win, especially when a worker is harassed by colleagues without direct authority over them. When a worker is sexually or racially harassed by their “supervisor,” however, the law recognizes that employers should have a special incentive to halt this kind of exploitation immediately. In many cases, when a worker is the victim of harassment by their boss, their employer is automatically liable for this harassment.

Except that, in Vance v. Ball State University, Alito’s opinion for a majority of the Court defined the word “supervisor” so narrowly as to render it practically meaningless. In Alito’s view, a person’s boss is only their “supervisor” if their boss has the power to make a “significant change in [their] employment status, such as hiring, firing, failing to promote, reassignment with significantly different responsibilities, or a decision causing a significant change in benefits.”

In a modern workplace, where final personnel decisions are often delegated to a distant human resources office, this means that few workers’ bosses will qualify as supervisors. Indeed, in dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg gives several examples of women whose bosses no longer count as “supervisors” under Alito’s framework. One of these non-supervisor supervisors was a man assigned to evaluate a female co-worker’s job perfomance, who then “forced her into unwanted sex with him, an outrage to which she submitted, believing it necessary to gain a passing grade.”

A Corporation’s Best Friend

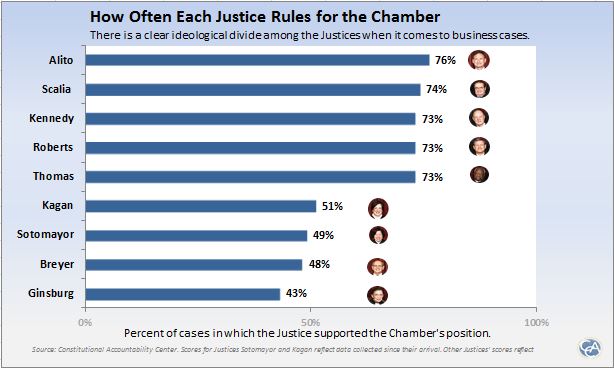

Lest there be any doubt, these three cases are not isolated decisions. The Constitutional Accountability Center (CAC) releases occasional reports tracking how often the Supreme Court sides with the United States Chamber of Commerce in cases where the Chamber files a brief. In large part because the Chamber is both a prominent corporate interest group and an especially active Supreme Court litigant, CAC maintains that tracking the Chamber’s performance is a good proxy for how likely the justices are to side with big business. Year after year, their data shows that Alito is a corporation’s best friend on the Court:

Other studies show similar results. According to data by Washington University Professor Lee Epstein, Alito is more likely to cast a conservative vote than anyone else on the Court.

To be fully precise, that does not make Alito the Court’s most conservative member. That honor belongs to Justice Clarence Thomas, who is the only member of the Court who openly pines for the days when federal child labor laws were considered unconstitutional. Yet, while Alito can’t match Thomas’s radicalism, he is far and away the most partisan member of the Court.

To explain this distinction, Thomas not a partisan. He is an ideologue. His decisions are driven by a fairly coherent judicial philosophy which would often read the Constitution in much the same way that it was understood in 1918. While this methodology typically leads him to conservative results, it does occasionally align him with the Court’s liberals. In 2009, for example, in a case brought by a drug company seeking lawsuit immunity after one of their products caused a woman to lose her hand, Thomas arguably took a position well to the left of the Court’s liberal bloc. While Justice John Paul Stevens wrote an opinion for the Court rejecting the drug company’s quest for immunity, Thomas argued that the legal doctrine the drug company relied upon should be tossed out entirely.

What makes Alito a partisan is that there is no similar case where his judicial philosophy drove him to a result that put him at odds with his fellow conservatives. Shortly after Hobby Lobby was handed down, ThinkProgress contacted several legal scholars and Supreme Court advocates asking if they could identify a single closely divided case where Alito broke with his fellow conservatives to join the liberals. Most replied that they could not think of any. One, Boston College Law Professor Kent Greenfield, added that “Scalia is a Roosevelt liberal in comparison” to Alito. Another, a progressive attorney who frequently practices in Alito’s Court, wrote back with just four words — “Nope. He’s the worst.”

Kedar Bhatia, who compiles statistics on Supreme Court decisions for SCOTUSBlog, agreed that “I don’t believe there have been any true instances of a 5-4 majority with Ginsburg, Breyer, Stevens/Kagan, Souter/Sotomayor, and Alito,” (although he was able to point to a handful of cases where Alito joined a 5 justice majority that included one other conservative and three liberals). The four other conservatives, Bhatia added, “are more prone to creating that sort of lineup.”

In contrast to Alito, some of his fellow conservatives have joined 5-4 decisions that absolutely enraged many Republicans. Chief Justice John Roberts famously cast the key fifth vote saving Obamacare, while Justice Anthony Kennedy cast the fifth vote striking the anti-gay Defense of Marriage Act. Even Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court’s most outspoken conservative, once broke with the other four conservatives to join the liberals in support of a state fair lending law.

Nor is Alito’s partisanship matched by the Court’s left flank. Both Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan joined the Court’s conservatives in rewriting Obamacare to make its Medicaid expansion optional, a decision that deprived millions of Americans of health coverage. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg broke with her fellow liberals in a case brought by unions seeking to make it easier for them to collect funds. Justice Sonia Sotomayor sided with the conservatives in a major privacy case.

Fahrenheit 451

Alito is a reliable partisan, but it would be a mistake to dismiss him as a substanceless hack. Alito may be the smartest member of the Court’s conservative bloc, and he is their best questioner. Recounting the oral arguments in the Citizens United campaign finance case in his book The Oath, Supreme Court reporter Jeffrey Toobin recalled that “[i]t was easy to tell which way Alito was leaning, because his questions were so hard to answer for the lawyer he was targeting. Alito had a radar for weak points in a presentation.”

Indeed, Alito asked a question during the Citizens United argument which has come to define that case for many conservatives. If the Constitution permits campaign finance law to regulate movies and television ads intended to influence an election, Alito asked, could the law also do “the same thing for a book?” After Malcolm Stewart, a longtime Justice Department attorney tasked with arguing this case while the newly inaugurated President Obama was still filling the top jobs in the Solicitor General’s office, answered that books could be regulated under campaign finance law, the argument descended into what Toobin labeled an “epic disaster.”Alito had somehow recast a case about whether corporations could spend unlimited money to shape electoral results into a case about banning books.

Several months later, when Solicitor General (and future Justice) Elena Kagan reargued the case, she tried to undo the damage Alito’s question had caused by announcing that “[t]he government’s answer” to his question “has changed.” But the damage had already been done. Alito’s single question continues to inspire conservative talking points to this day. Just last month, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) labeled supporters of campaign finance regulation “Fahrenheit 451 Democrats.”

In 2005, when President George W. Bush announced Alito’s nomination to the Supreme Court, he praised his nominee as someone who “understands that judges are to interpret the laws, not to impose their preferences or priorities on the people.” Less than a decade later, Alito rewrote American religious liberty law, and he did so despite an explicit statement by Congress indicating that Hobby Lobby should have come down the other way. Along the road to Hobby Lobby, Alito made the workplace a harsher, meaner place for women. He inspired talking points for Ted Cruz. And he has an unblemished record as the most committed partisan on the Court.

And, unlike the many partisans in Congress and other elected positions, Alito cannot be voted out of office. His appointment to the Court lasts for his entire life.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.