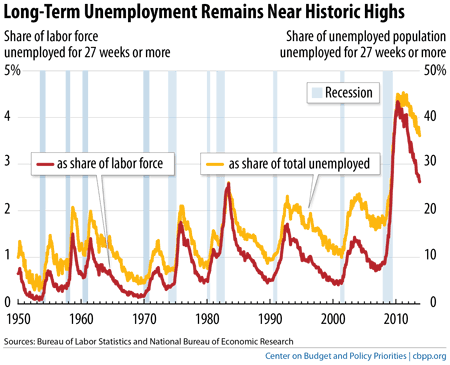

The emergency support program for the long-term unemployed which was first enacted in 2008 could face big cuts with the start of the New Year, even though the recovery remains tepid and unemployment figures remain higher than at this point in any previous recession. And many experts are saying that further austerity would bring more bad news for the economy.

Chad Stone, chief economist at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities — a think tank focused on policies to help low- and moderate-income Americans — writes, the “mainstream explanation for why unemployment is so high is that businesses still don’t have enough sales to justify hiring enough workers to restore normal levels of employment.” Failing to renew the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program, which has been extended a number of times since 2008 to help those struggling during the Great Recession, will have the opposite effect of what is needed — Americans out-of-work for long periods will have even less to spend, which will further blunt the already-pretty-blunt recovery.

“With an unemployment rate of 7.3 percent, we need to raise the emergency unemployment insurance (UI) and push for extensions to 2014,” Gene Sperling, director of the White House’s National Economic Council, said at a public forum last week. Sperling claimed he “sees a good chance to get a new reform through Congress,” the MNI financial news service reported.

But right now, House Republicans have not shown much interest in coming to an agreement to extend the program. “The current EUC program already has served up about 10 times as many weeks of federal extended benefits as the most recent program that operated in the wake of the 2001 recession and terror attacks, and nearly six times as many weeks as the program that ran from 1991 through 1994,” said the House Ways and Means Committee chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) in a press release. “And despite Democrat claims that such spending on UI benefits is the ‘best stimulus,’ all this record-setting benefit spending has bought is the slowest recovery on record.”

Stone says that is an unfair characterization based on an analysis that puts the cart in front of the horse. “To be sure, EUC has lasted a lot longer, helped a lot more unemployed workers and paid out substantially more in benefits than the programs enacted in past recessions. But that’s because the blow to the economy and especially the labor market from the Great Recession was so much worse. In fact, without the consumer spending UI generated, the recession would have been even deeper and the recovery even slower, according to conventional economic analysis.”

Annie Lowry wrote in The New York Times this weekend that long-term unemployment is a trap that becomes more and more difficult to escape with each passing month. Since the Great Recession started, long-term joblessness is up 213 percent, and economists are unclear about whether faster growth will improve the situation. Many of the long-term unemployed have rusty job skills that will make re-entering the workforce tough, even if more jobs become available. Others have ruined credit ratings, which employers increasingly rely on to screen new hires. And unemployment carries a heavy stigma that keeps people out of work. “We don’t hire the unemployed,” a potential employer told Jenner Barrington-Ward, a 53-year-old college graduate who had worked steadily for 30 years before being unemployed for the past five.

Lowry writes:

[T]he slack economy remains the primary culprit behind all the pain in the labor market, economists say. “We’ve got to be doing everything we can,” said Professor Rothstein at Berkeley. “That means direct hiring”— with the government providing jobs — “employment tax credits, just about anything you could think of.”

But the government is now doing the opposite. The mandatory federal budget cuts known as sequestration took as much as 60 percent out of unemployment checks this summer and fall. And, as of this winter, the federal emergency program that extends the maximum number of weeks of jobless payments will end, though the White House is pushing to extend it again.

Some fear that it may already be too late to prevent long-term joblessness from permanently scarring the American work force and broader economy. International Monetary Fund researchers estimate that the level of structural unemployment has increased significantly since the recession. And striking new Federal Reserve research shows that the scars from the recession have knocked the economy off its long-term growth trend.

It’ll fall to Congress — specifically, to the House of Representatives — to determine whether unemployed Americans, and by extension all Americans, have a depressing New Year.