This week marked the four-year anniversary of the last time Congress increased the minimum wage — from $5.15 in 2007 to $7.25 in 2009. Groups demonstrated across the country, demanding increases at both the state and federal level. President Obama pledged that he would continue to press for an increase in his economic policy speech at Knox College.

But there’s another problem: Millions of working Americans make less than minimum wage. In fact, more Americans are exempt from it than actually earn it.

The Pew Research Center examined Bureau of Labor Statistics data and found that about one and a half million Americans earned the minimum wage in 2012, but nearly two million people earned an hourly wage that was even less than $7.25 an hour. These workers, for one reason or another, are exempted from the part of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FSLA) that requires employers to pay at least the minimum wage, and include tipped workers and many domestic workers, as well as workers on small farms, some seasonal workers and some disabled workers.

The largest of these exempted groups is tipped employees, many of whom work in food service. Today, tipped employees earn just $2.13 an hour — the rationale being that tips cover the rest. In fact, some of these workers do earn a reasonable living through their tips, but, as Saru Jayaraman, co-founder and director of the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, told us, many don’t.

“Imagine your average server in an IHOP in Texas earning $2.13 an hour, graveyard shift, no tips,” she said. “The company’s supposed to make up the difference between $2.13 and $7.25 but time and time again that doesn’t happen.”

The Obama administration proposal laid out in the State of the Union calling for $9 an hour also called for an increase in the minimum wage for tipped workers, and for that increase to be indexed to inflation. At the moment, the minimum for tipped workers has not changed for 22 years, because, in 1996, Congress detached tipped worker wages from the normal minimum wage at the bidding of the National Restaurant Association — a powerful lobbying organization headed, at the time, by Herman Cain. This leaves millions of tipped workers — a group that is mostly women — living in poverty.

Another large subset of American workers exempted from both minimum wage and overtime pay is domestic workers who provide “companionship services.” The actual duties of these workers range from providing medical care to the disabled and the elderly to helping with basic tasks like eating, dressing and bathing, shopping, transportation and cooking.

The “companionship” exemption was first created in 1974, when the FSLA was extended to cover domestic workers. At the time, in-home caregiving was a relatively small industry. But it’s grown; in 2011 the National Employment Law Project estimated that about 1.7 million Americans fell under the exemption. On Tuesday, hundreds of domestic workers rallied near the Department of Labor headquarters, urging newly confirmed labor secretary Thomas Perez to take action and extend to them the same workplace protections almost all other Americans enjoy. Vice President Joe Biden expressed his support for doing so last month, as did Obama in 2011.

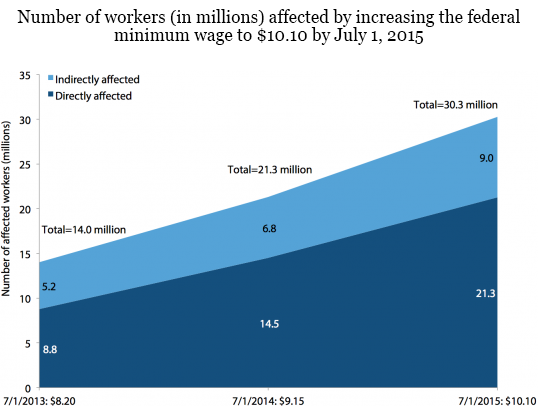

Three and a half million workers make either minimum wage or less than it — that’s at most $15,080 a year, well below the poverty line for a family of two — and millions more Americans make something only slightly above it. Raising the minimum wage to $10.10 by 2015 , as many of the protests this week urged, would mean higher wages for the 21.3 million Americans who make less than that. The Economic Policy Institute blog reports that it would create a ripple effect, leading to higher wages for a total of 14.2 percent of all U.S. workers, creating a mild economic stimulus, helping to close the gender pay gap and decreasing income inequality.

Economic Policy Institute.

Recent polling has found that the majority of Americans, regardless of political party affiliation, support an increase to $10.10. And if Congress makes the (what seems at the moment unlikely) decision to take action and raise the minimum wage, pulling millions out of poverty, they should also reexamine the loopholes that exclude some two million American workers from the minimum.