Being young and black in America today must be hard. The experiences of black youth are so often left out of the national discourse, it probably seems like no one really understands their plight. On the few occasions that stories about them appear in pop culture, particularly television and film, they’re often shown in one of two ways — the overachiever, the kid that “makes it” despite the odds, like Jay-Z, or the lazy underachiever, the thugs and welfare moms that so many on the right often allude to.

It’s easy to understand why this happens. In the more than four decades since the Civil Rights Movement, black youth are still lagging behind. Many of the statistics and stories that we hear about young African Americans, much like the ones Bryan Stevenson shared on recent Moyers & Company shows, are abysmal. Add in the other “isms” that all too many black youth are familiar with, like classism and sexism, and you can see why there’s an anxiety about the state of young black America.

One of the stories that did receive a lot of media attention in the recent past is the Trayvon Martin case. He was the teen killed last year in Florida by a man who allegedly thought he was threatening his life. Putting the politics of the case aside, Trayvon, a young middle-class black kid, with two involved (if not together parents), who liked hoodies, his girlfriend, Twitter and Skittles, is probably a good example of your average black kid. But how much does America really know about the Trayvons of the world except when violence intervenes? When do their stories get told? When do we understand that most black kids aren’t all that different from white kids?

I know a bit about this because growing up I was that Trayvon. I wasn’t what many would classify as a “burden” to society, but I wasn’t the next Barack either. I lived in a single parent household that was loving and instilled the values of hard work and sacrifice. And I was far from an anomaly. I was surrounded by other black families like mine, some with more money, some with less, some with fathers and mothers together, some with only fathers, but many were happy, working and middle-class Americans.

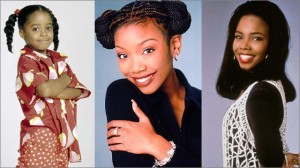

In the eighties and nineties, mainstream network television and film was better about showing middle-class black families. Girls like Moesha, Rudy Huxtable and Laura Winslow looked like me. Today however, with a decreasing number of black family shows — and an explosion of celebrity culture — storylines about average black youth are even rarer. While it’s a great testament to our nation’s progress to have stories about Will Smith’s talented kids and Obama’s smart girls, we need to make “ordinary” black kids a commonplace as well.I’m lucky that the lives of black youth aren’t hidden to me. I am surrounded by a number of young black men and women that are doing well, that are smart and talented and talk endlessly about annoying parents, relationships, and even politics. But popular culture is a powerful tool. It shapes and defines many of our beliefs about our larger society. And while it is important to voice the stories of those that need it the most — those that have been left behind, discriminated against and crippled by injustice in an all too often unequal society — we must also hear more about ordinary black kids, who are more the norm than the exception.