We’re proud to collaborate with The Nation in sharing insightful journalism related to income inequality in America. The Nation contributor Greg Kaufmann writes a weekly roundup on the topic, “This Week in Poverty.” Share your thoughts about these must-read stories and always feel free to suggest your own in the comments section.

Before there was Clinton-Gingrich Welfare Reform in 1996 there was Mississippi Governor Kirk Fordice’s “Work First” pilot program in 1995.

That year, the Clinton administration granted the Republican governor a waiver to implement a new work requirement in six counties that Fordice claimed would result in 50 percent of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) recipients getting off welfare and into jobs within three years.

One of the targeted counties was Harrison County, where Reverend Carol Burnett was running a literacy program for low-income women in east Biloxi. Burnett—one of the first women United Methodist ministers in Mississippi—would later serve as director of the state’s Department of Human Services (DHS) Office of Children and Youth in a Democratic administration.

“The women in this program were just trying to learn basic literacy skills, hoping they would be able to continue their education and get decent jobs in the future,” Burnett tells me. “Under the first President Bush women were allowed to pursue education while receiving welfare support. But the Mississippi pilot program changed that.”

Women were quickly forced out of literacy and other education programs to work as security guards, shrimp pickers, fast food workers, in poultry plants or at other low-wage jobs.

“We’re talking about low-wage jobs without the possibility of promotion, since the women didn’t have the education level needed for promotion,” says Burnett. “And a lot of seasonal jobs that were obviously short-term too.”

A 1996 report from graduate students at the University of Southern Mississippi’s School of Social Work indicated that women were also forced from GED programs, and two-year associate degree programs, in order to take Work First jobs. Some did so despite lacking access to childcare—even when working night shifts—so children were placed in situations that increased their risk of suffering abuse or neglect.

In 2011, Earline Malone closed the childcare center she'd operated in downtown Pickens, Mississippi since 1993. Because so many parents in the area were unemployed or underpaid, they could not afford childcare and Malone could not keep her business open. In this AP photo, Malone, standing outside her closed daycare facility, expressed concerns about the economic survival of families in Pickens and the Delta. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

“How feasible is it to expect mothers to care for children, work in a minimum wage job, and obtain an education on their own time with unreliable or no transportation, and no child care provided?” the report authors asked. “Most analysts agree that post-secondary education targeted to living wage jobs would provide a more realistic pathway out of poverty for mothers and their children.”

When public hearings were held to assess the Work First program and whether it should be rolled out statewide, Burnett shared the report with state legislators.

“We were telling them that this was a terrible idea, that it would be devastating,” says Burnett. “That it was locking poor women into low-wage work that would keep them mired in poverty.”

Not only was the report ignored, but the Fordice Administration allegedly threatened to terminate DHS’s training contract with the university for making the report public. Before the hearings were completed, President Clinton signed welfare reform into national law, replacing the AFDC cash assistance program with Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF)—very similar to the Work First program. The report by the grad students of Southern Miss would prove prescient.

Today, it is very difficult for women to use education to count towards their TANF work requirement. Instead, most are stuck in low-wage jobs, earning a welfare benefit that is below 30 percent of the poverty line in most states (below $5,300 annually for a family of three). If they find a job that pays slightly better—a job that could get them off of TANF—they risk losing childcare, so the pay raise might be negligible or even a net loss. Currently, only about one in seven families qualifying for federal childcare assistance actually receives it.

Welfare reform also created lifetime limits, which range from twenty-one months to five years, depending on the state. It mandated that states sanction recipients off of TANF if they don’t meet their work requirement. That’s in part why we see an increase in the number of women and children in deep poverty, which is less than half the poverty line—less than $9,000 annual income for a family of three. 20 million Americans—one in fifteen—now live in deep poverty; up from 12.6 million in 2000, or an increase of 59 percent.

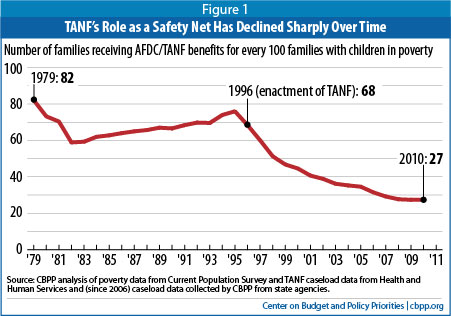

In all, the TANF program now reaches approximately 27 families for every 100 families with children in poverty. Its predecessor, AFDC, reached 68 families for every 100 families with children in poverty. Yet both parties widely proclaim welfare reform a success and the media rarely challenges this notion.

In all, the TANF program now reaches approximately 27 families for every 100 families with children in poverty. Its predecessor, AFDC, reached 68 families for every 100 families with children in poverty. Yet both parties widely proclaim welfare reform a success and the media rarely challenges this notion.

During the brouhaha over Governor Mitt Romney’s ads and stump speech that falsely accused the Obama administration of ending the work requirement for TANF, there was little substantive coverage of the issue. The commentary focused almost exclusively on calling out Romney’s lie, and the Obama campaign’s retort that any new TANF waivers would actually raise the number of welfare recipients working by 20 percent.

It was a missed opportunity to ask pressing questions, like: Why is TANF failing to help lift families out of poverty and leading to fewer people getting the assistance they need? Why are women now 34 percent more likely than men to be in poverty, despite above average employment rates compared to single mothers in other high-income countries? Why is the block grant the same as it was in 1996—as if we could cap economic need and pain—and not indexed to inflation? Why have real benefits levels fallen by 20 percent or more in thirty-four states, even as caseloads have declined? How are states using that money that used to go directly to poor families?

It seems more fashionable these days to simply blame single mothers for their struggles—either subtly, or not so subtly. Even New York Times reporter Jason DeParle recently noted research saying that “single parenthood explained about 40 percent of inequality’s growth.” He then suggested, “Marriage…can help make men marriageable.”

The implication is that by simply marrying, single mothers will end up with a good partner—even if the partner initially seems not so “marriageable”—and rise from their economic struggles. Absent from this article and too many others is any significant discussion of the policy choices that are making the lives of single mothers and their children harder: a lack of childcare, a federal minimum wage stuck at $7.25 an hour, no paid sick leave and no pay equity, unaffordable healthcare, to name just a few.

“Rather than continuing to blame women on welfare for imagined deficiencies, new policies are needed which support single women in their breadwinner roles,” wrote the Southern Miss grad students sixteen years ago. “Policy goals of increasing wages, providing quality childcare, and investing in training and education of low-income women would be more appropriate to actual needs, and would begin to address the core problems of poverty.”

Today, as the founder and executive director of the Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative, Burnett is still fighting to help low-income parents get the child care they need. But there are now over 8,000 children on the waiting list. And when parents hit their lifetime TANF limit, they not only lose cash assistance but child care as well, and childcare centers lose a reliable source of income—ninety-six have shut down in the past year. The state is, however, investing in new fingerprint scanners to use on parents who receive a childcare subsidy.

Knowing there is little chance for new funding with a Republican governor, State House and State Senate, Burnett is locked in a freedom of information battle in an effort to determine how Mississippi is spending its TANF block grant. The monies can go to a broad range of activities that have nothing to do with childcare or cash assistance, and also have been used to “plug holes in state budgets or free up funds for purposes unrelated to low-income families or children,” according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP).

So far, Burnett has only received information on about $8 million of the state’s $90 million block grant. In 2001, she and her colleagues at DHS learned that the previous Republican administration had allowed $69 million in TANF money to go unspent. The lack of transparency on how the resources are being used is hardly unusual. The US General Accountability Office reports that “there is little information on the numbers of people served by TANF funds other than cash assistance.”

Mississippi now ranks worst in the nation with 31.8 percent of children living in poverty, and worst in the nation in child well-being according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s 2012 Kids Count Data Book, a national and state-by-state effort to track the well-being of children. For every 100 families with children in poverty in the state, only ten now receive TANF cash assistance. In 2009–10, according to the CBPP, there were 117,327 families with children in poverty, and just 11,773 TANF cases.

As for those parents who are being sanctioned off of welfare because they are unable to meet the work requirement or they reach lifetime limits:

“They are now virtually invisible to the country and in the current political discourse,” says Burnett.

Clips

“…Wal-Mart Continues to Defend Unequal Pay Practices,” Sheila Bapat

“Welfare Cases in Ohio Tumble,” Kate Giammarise

“…Plugging Disconnected Youth Back into the Labor Market,” Linda Harris

“Child Poverty Rate Rising in Many States,” Julia Isaacs

“2011 State Poverty Data Underscore Need to Protect Programs for Low-Income Women,” National Women’s Law Center

“Standing Up for Teachers,” Eugene Robinson

“I Was a Welfare Mother,” Larkin Warren

“Chicago Teachers Go to Bat—and Take a Hit—for Their Students,” Elaine Weiss

Studies/Briefs

“Reducing Poverty in Wisconsin: Analysis of the Community Advocates Public Policy Institute Policy Package,” Linda Giannarelli, Kye Lippold, Michael Martinez-Schiferl, Urban Institute. Analysis shows that a package of policies developed by Community Advocates Public Policy Institute could reduce Wisconsin’s poverty rate by 58 to 66 percent. The policies include a Senior and Disability Income Tax Credit, transitional jobs, an increase in the minimum wage to $8, and expansion of income tax credits related to earnings.

“The State of Working America: Poverty Fact Sheet,” Economic Policy Institute. Americans are working longer and harder but becoming poorer and less economically secure. In 2011, 28 percent of workers earned poverty-level wages. Income inequality is the largest factor contributing to higher poverty rates. Increased numbers of minorities and single-mother-headed households are often cited as determinants of higher poverty rates, though they are much smaller contributing factors.

“Maintaining and Strengthening Supplemental Security Income for Children with Disabilities,” Rebecca Vallas and Shawn Fremstad, Center for American Progress. Supplemental Security is an effective support for children with severe disabilities and their families. Among its strengths, it reduces poverty and increases economic security by offsetting some of the extra costs and lost parental income associated with raising a child with a severe disability; it also supports work and education for parents and youth. This brief examines how it can be strengthened to further increase economic security and opportunity for children with disabilities and their families.

Get Involved

No Kid Hungry: Watch and Share Protect SNAP Video and Take Action Now

#TalkPoverty at the Debates

Dear Mr. Lehrer

Vital Statistics

US poverty (less than $23,021 for a family of four): 46.2 million people, 15 percent.

Children in poverty: 16.1 million, 22 percent of all children, including 39 percent of African-American children and 34 percent of Latino children. Poorest age group in country.

Poverty rate among families with children headed by single mothers: 41 percent.

Deep poverty (less than $11,510 for a family of four): 20 million people, 1 in 15 Americans, nearly 10 percentof all children.

Twice the poverty level (less than $46,042 for a family of four): 106 million people, approximately 1 in 3 Americans.

Jobs in the US paying less than $34,000 a year: 50 percent.

Jobs in the US paying below the poverty line for a family of four, less than $23,000 annually: 25 percent.

Youth employment: lowest level in more than 60 years.

Poverty-level wages, 2011: 28 percent of workers.

Families receiving cash assistance, 1996: 68 for every 100 families living in poverty.

Families receiving cash assistance, 2010: 27 for every 100 families living in poverty.

Gender gap, 2011: Women 34 percent more likely to be poor than men.

Gender gap, 2010: Women 29 percent more likely to be poor than women.

People age 50 and over at risk of hunger every day: 9 million.

Impact of public policy, 2010: without government assistance, poverty would have been twice as high—nearly 30 percent of population.

Impact of public policy, 1964–73: poverty rate fell by 43 percent.

Quote of the Week

“Judge-and-punish-the-poor is not a demonstration of American values. It is, simply, mean. My parents saved me and then—on the dole, in the classroom or crying deep in the night, in love with a little boy who needed everything I could give him—I learned to save myself. I do not apologize. I was not ashamed then; I am not ashamed now. I was, and will always be, profoundly grateful.”

—Larkin Warren, “I Was a Welfare Mother“