Richard Hasen’s new book The Voting Wars chronicles the partisan battles over election rules from the 2000 Florida recount to the present. The story continues on his Election Law Blog, the go-to source for updates on the wave of new voter ID laws, registration roll purges, and other efforts to manipulate voter turnout and potentially skew elections. We caught up with Hasen to talk about election fraud, voter suppression and the chances that either could make the difference in a close election this November.

Lauren Feeney: What’s been the legacy of the Florida recount of 2000 (aside from the eight-year presidency of George W. Bush, of course)?

Rick Hasen: People learned the wrong lesson in Florida. They learned how election rules could be manipulated for partisan advantage; that you could try to game the refs in terms of what rules are in effect and how the votes are counted; that going to court is sometimes a successful strategy for changing the rules for counting the vote after the election. They learned, essentially, that election law can be used as a political strategy.

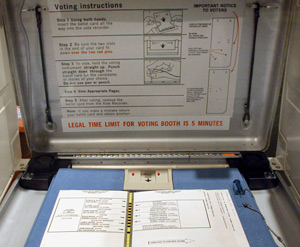

The good news is that we’ve made tremendous improvements in the technology we use for casting and counting ballots. There are now millions more votes that will be counted instead of being lost by bad technology. Unfortunately, that’s the only good news; the rest of the news is bad.

Feeney: What is the most common type of election-related fraud?

Hasen: We see many more cases of fraud related to election officials or absentee balloting than impersonation fraud. For my book The Voting Wars, I could not find a single case in the last generation where it’s even remotely possible that impersonation fraud without the collusion of election officials was responsible for changing an election.

Feeney: Who are the main forces behind some of these new laws, purges and restrictions that are part of this effort to use election law as a strategy?

Hasen: Most of the new laws have passed on party lines. So if you look at the new voter identification laws, with the exception of Rhode Island, they’ve passed on almost straight party-line votes, with Republicans supporting such laws and Democrats opposing them. The controversial pro-business group ALEC has been responsible for putting voter ID on the agenda in a lot of these states.

The Bush administration really pushed the claim that there was a lot of voter fraud, and The New York Times had an excellent article summing up the results. There were very few cases of voters actually committing fraud; more cases of election officials committing fraud, and not a single case of impersonation fraud.

In the meantime, a close ally of Karl Rove named Thor Hearne started a group called the American Center for Voting Rights, which set itself up as a kind of think tank trying to show that voter fraud was a major problem in this country. It produced no original research, and much of the research it put out was debunked. But Hearne testified at all of these hearings about the prevalence of voter fraud and used it to argue in favor of voter identification laws and other laws which seemed to be intended to at least modestly suppress Democratic turnout. One day, the center simply disappeared, its website disappeared, Hearne has scrubbed his affiliation with this group from his resume; it’s as if the group never existed. There are some people — I call them the ‘fraudulent fraud squad’ — who raise allegations of serious impersonation fraud, but when you push them on it or you check out the details, it almost always turns out that they were talking about a debunked claim, an exaggerated claim, or a claim about a kind of fraud that has nothing to do with voter identification.

Feeney: Can you compare the number of legitimate voters who stand to be disenfranchised by some of these new rules like voter ID to the number of fraudulent voters who might stand to be blocked by these efforts?

Hasen: Overall, election fraud is a relatively small problem, but when it does occur, it tends to occur in one of two ways: either through corrupt election officials who change vote totals or do other things to affect election outcomes, or through absentee ballots, which can be bought and sold. Every year we see prosecutions and convictions for absentee ballot fraud, some of which has actually changed the results of elections.

The principal kind of fraud which a voter identification law would prevent is voter impersonation fraud; that is, one person going to the polls and claiming to be somebody else on the rolls. This kind of fraud is extremely rare. A recent News 21 study looked at all election-related prosecutions over the last decade in all 50 states, and found at most 10 cases of prosecutions, compared to hundreds of cases of absentee fraud and election official fraud.

It’s no surprise that the numbers are so low, because voter impersonation fraud is an exceedingly dumb way to try to steal an election. It’s just not done, because you’d have to have enough people going into the polling place pretending to be someone else, knowing those people who they’re pretending to be are not also going to vote, and not being able to verify how these fraudulent voters are going to actually cast their ballots.

On the other side of the ledger, how many people could be disenfranchised by these laws? We don’t have very good figures on this, but Democrats tend to exaggerate the numbers. You’ll hear that millions of voters are being disenfranchised. I don’t believe that this is a fight over millions of voters; I think it’s a fight at the margins. Perhaps we’re talking about 1 percent, perhaps a little more. But in a very close election, with these voters skewing Democratic, removing 1 or 2 percent of Democratic voters from the rolls could be enough to make the difference between a Democratic victory and a Republican victory.

Learn more about election law at Hasen’s Election Law Blog or follow him on Twitter @rickhasen.