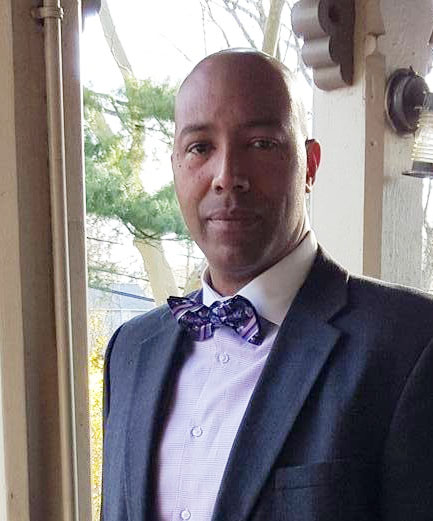

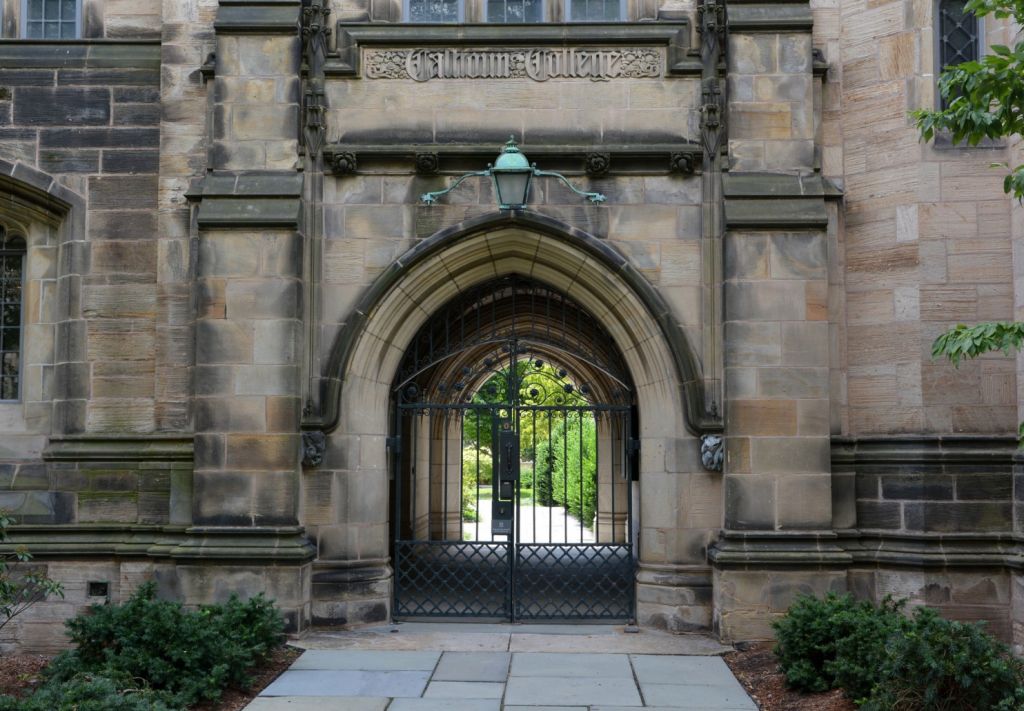

A view of Calhoun College at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. (Photo by Michael Marsland/Yale University)

You can learn a lot about what is and isn’t in a name growing up in low-income urban America. Names can be fluid. Sure, everyone has the name their parents gave them, but they might also have one or many street names that indicate an attitude, a skill or a warning. Names can be dynamic to express oneself to the world. And you might find yourself in real trouble if you’re not from a particular neighborhood and start calling people out by their street names without knowing them. You have to earn that right. In this case, a name is close to sacred and represents a key to inclusion.

Is this the way names work for other kinds of things in the world, like old buildings on college campuses? Consider the example of Yale University’s residential hall, soon to be formerly known as Calhoun College. John C. Calhoun was the seventh vice president of the United States, and he was also a proponent of slavery, nullification and states’ rights in service to Southern social and political interests (read: white supremacy). And yet since 1931, Yale University has had on its campus a staid building named after Calhoun, a person that no decent human being could venerate as admirable or worth honoring.

It was with this reasonable judgment in hand two years ago that students and faculty began to mount protests demanding his name be stripped from the residential college. Against the backdrop of unpunished police shootings of unarmed blacks across America, the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, racially charged events on many college campuses — including Yale’s — and, finally, Yale’s ongoing difficulties with diversifying its faculty, there arose a sensibility that the Calhoun name was not just one offense too many, but an emblematic one, a continued disregard for the perspective of marginalized populations. It hadn’t seemed to be taken seriously by administrators that a black student might bristle at spending four years living in a building that seems to honor white supremacy.

At first, Yale’s administration seemed unmoved, initially announcing the Calhoun name would remain. President Peter Salovey expressed concerns about erasing Yale’s history, saying it is more important to tell the truth about the past. But, then, in a somewhat surprising reversal, Salovey announced last month that Calhoun College would be renamed after Grace Hopper, a pioneering mathematician and computer scientist who joined naval efforts during World War II to combat fascism at a time when women were rarely allowed access to technical learning, much less to lead innovation.

It seems to me a good thing that a building be named after Hopper. In a world that still minimizes women’s roles in science, math and industry, Hopper’s name is a welcome recognition of women’s contributions and equal capabilities.

Yet it might take a bit of different vision — let’s say the kind molded by lessons learned on America’s urban streets — to see that renaming a building might not be the most complete way to agitate for social justice. On the streets one might be made to pay for saying a name one wasn’t authorized to say in public; it might be worth thinking about exacting a cost on institutions across the nation for “shouting” a name they had no business shouting around students being educated in the liberal tradition in a country that can’t seem to fully undo its racist past.

In recent years, similar controversies have played out at Georgetown, Princeton and the University of Texas at Austin, among others, and I have wondered whether sites like Calhoun can be made to serve as cautionary tales in a manner productive to locally suppressed populations.

The city of New Haven, for example, is home to a very significant black and brown population that is disproportionately affected by unemployment. Changing a building name at Yale or Princeton or any other elite institution is ultimately costless save to those elites with a perverse idea of “honoring history.” When a name is changed the victory is an important symbolic one, yet most salient for those who are already experiencing remarkable privilege.

If the problem with names like Calhoun is that they represent ongoing legacies of inequality and oppression, it follows that a core problem to be addressed is exactly those ongoing conditions. The name is an entry point, a signal that our collective social consciousness needs to be raised, not just for the sake of acknowledgement but as a call to take action. Consider that disadvantaged populations, often on the geographical margins of our powerful sites of learning, continue to face the daily grind of the kind of social and economic inequality such institutions tend to perpetuate. One way to make institutions directly confront the legacy of honoring names like Calhoun’s would be to institute a well-funded, long-term fellowship program at places like Calhoun College whereby students can compete for significant funds to connect with their local communities.

In New Haven, well-funded students could work to help provide adult education, job training and even technological skills to residents and do so by holding such workshops right on the grounds of Calhoun College. In this way, the Calhoun name is undercut most meaningfully — as a lesson that when institutions take too long to undo their relationships with offensive histories, they must make amends to the representative populations that in fact continue to struggle against the legacies resulting from these histories. In other words, the woman or man on the street, in addition to the student in the dorm and faculty member in her office, must demand that one earn the right to say the proper name, and made to pay when we say the wrong one.